LEGACY BUILDING

THE REWARDS OF GETTING FARM SUCCESSION RIGHT

BY CLARE STANFIELD

Merle Good has a farm succession presentation titled, “The Impossible Dream?” That question mark says it all when it comes to the way most people feel about, and approach, the task of farm succession. While it’s most definitely a complicated task, it can be extremely rewarding and is by no means impossible.

“Look at it from a legacy perspective,” said Elaine Froese, a certified farm family business coach, conflict resolution facilitator and a farmer from Boissevain, MB. “What do you want your legacy to be?”

Most farmers approaching retirement age might say they want their farms to stay in the family and go on indefinitely. But accomplishing that feat means letting go sooner, and that’s where things start to get tough. “One of the reasons for procrastinating over farm succession is that many farm managers can’t let go of power and control without having something more exciting to go to,” said Froese.

And there’s the rub: how do you transfer a business that is also your life?

Froese and Good, who is a farm business advisor from Cremona, AB, have seen that dynamic play out thousands of times in their work.

“A farm has two pillars, family and business, and they’re always intertwined,” said Good. “You are always balancing the family dynamics with the business opportunities.”

Both agree that succession planning and estate planning are different things. “Succession is the transfer of the business,” said Good. “Estate planning is the transfer

of wealth.”

However, even that line of thinking still leaves many farm families feeling overwhelmed by the process. Maybe this notion is too often missed: that succession is more aptly called a process than a plan—the latter being a word that hints at something fixed with step-by-step instructions and an end point.

A good succession plan isn’t something you do once and it’s done. It’s something you live. As Froese noted, it should constantly evolve and be flexible enough to change as business and family circumstances change. “It’s a journey,” she explained. “It’s not a quick-fix solution; things are always evolving and changing. But that can be very exciting.”

MAKING WAY FOR THE YOUNG

“After this first year, I know we made the right choice,” said Hannah Konschuh.

In their late twenties, Konschuh and her fiancé, Casey O’Grady, are at the beginning of a farm succession process involving her parents, Sheila and Eldon, and the grain farm she grew up on near Cluny, AB. They both left good jobs with pensions in Saskatoon to climb back into a tractor and build their future on the land.

“Before we made the move, we had a lot of conversations to discuss our respective visions and expectations,” said Konschuh.

In an industry where stats suggest that farmers are getting older and not enough young people are stepping into the gap, Konschuh and O’Grady could be on the leading edge of a turnaround. “From 1990 to 2000, no one was coming home—there was no money in ag,” said Good. “But from 2000 to 2015, there has been tremendous income generation. And what spurs business transfers is economics.”

Relatively recent Statistics Canada figures back up the point, showing that average total farm sales for oilseed and grain operations went from nearly $217,000 in 2009 to almost $400,000 in 2013.

Land values have gone up, too. According to Farm Credit Canada, the average value of Canadian farmland went up 14.3 per cent in 2014, maintaining an overall upward trend since 1993. In Alberta, where Konschuh and O’Grady are starting out, land values went up 8.8 per cent in 2014—a bit of a slowdown after two years of double-digit growth—driven largely by higher commodity prices.

But the couple isn’t thinking about the price of land just yet. The arrangement they have with Konschuh’s parents is that they will rent a portion of the 5,500-acre grain farm for a two- to three-year period as a trial to see how a succession process could work for them. “The equipment and labour are shared, but we are our own farm entity,” said Konschuh.

She said open communication and setting clear goals have been key to a successful first year. And, for now, they’re doing it on their own through regular business meetings. “Very early on, we all agreed that we wanted to utilize a facilitator,” said Konschuh. “We thought we’d get through the first year and pinpoint the challenges that might exist for our operation, and then bring in a facilitator.”

She’s clear that this is not about conflict, saying that a facilitator can help all parties redefine their goals, consider new angles for achieving them and perhaps point out avenues not considered before. “Some people think you need to bring in a facilitator to solve major conflicts,” said Konschuh. “But we see facilitation as an important tool for business planning.”

WHAT ABOUT THE LAND?

At some point, Konschuh and O’Grady will have to start thinking about buying the land, or at least taking it over in one form or another.

Herein lies one of the biggest bugaboos of succession: with land values on an unbroken 22-year climb, how can young people afford to get in and, at the same time, how can their parents afford to get out? It doesn’t help that land is a highly emotional issue.

“I tell clients, ‘Forget the land altogether and focus on the business,’” said Good. “And when I say that, I can see the angst going away and the blood pressure go down. I tell them, ‘Let’s park the estate planning for now and look at the business. Is there an opportunity for this young person to make a living?’”

Which is exactly the question Harvey Pederson asked himself back in the late 1970s when his oldest son, Brian, graduated high school and said he wanted to farm.

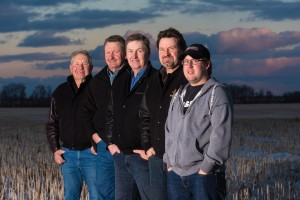

“Dad looked down the road and wondered how to get someone in, and give them a sense of ownership when they had no assets,” said Terry Pederson, the second of Harvey and Mildred Pederson’s three sons, all born in the early ’60s.

The family farm in Bawlf, AB, wasn’t huge at the time—roughly 1,000 acres. Harvey decided to give Brian 10 per cent of the farm’s income on all the acres, and bill him for 10 per cent of the input costs associated with those acres—seed, fertilizer and fuel. The land and equipment was shared at no cost.

“The next year, I graduated and I wanted to farm, too,” said Terry Pederson. “Dad says to Brian, ‘You have some dollars in the bank now, so you move to 20 per cent of the income, but you also assume 20 per cent of all the expenses,’ and I got the same deal Brian did coming in.”

Two years later, the process was repeated when the youngest Pederson son, Rick, came home to farm. By the time he was in his second year, all three boys had assumed a 20-per-cent share of the farm’s income along with a 20-per-cent share of all expenses—including capital expenses, like equipment—while their father assumed 40 per cent.

And thus, Pederson HBTR (Harvey, Brian, Terry, Rick) was formed, a joint-venture arrangement where all profits and expenses (capital and operating) were split 40-20-20-20.

The question now was how to bring more land into the operation. The deal Harvey and Mildred worked out was that when any of their sons bought land, it would be rented back through the joint venture. Essentially, this created a rent-cropping scenario where the person who bought new land would receive 35 per cent of its crop value, while Pederson HBTR received 65 per cent, which, in accordance with the joint-venture arrangement, would then be split 40-20-20-20.

For example, if Terry bought land and rented it to the joint venture, he’d receive 35 per cent of the crop value as the landowner, and an additional 13 per cent (20 per cent of 65 per cent) as his share of Pederson HBTR, for a total of 48 per cent of the crop value off his piece of land.

When Harvey bought land, however, he did not lease it to the joint venture, but included it in the farm’s overall land base, simply sharing the crop value through the 40-20-20-20 agreement. “Any new land I buy, I don’t charge rent on,” he said. “It’s just part of the farm.”

Even Harvey has a little difficulty explaining this decision. Mainly, he does it because he believes it’s the right thing to do. With 40 per cent of overall crop value coming to him, he doesn’t feel the need to take additional income in rent, particularly as it would, technically speaking, be coming out of his sons’ pockets. “I didn’t want to end up with a better income than they did,” he said, explaining the importance to him that everyone has a similar income level.

For Harvey, it’s also about building a stronger business. “I wanted an incentive for them to want to buy land,” he said. “Any land they own, they get 48 per cent, so that’s quite an incentive.”

It’s not only an incentive to buy land and expand the business, he added, but also to take pride in their land and look after it. It means that everyone shares in the value of the crop, regardless of whose land it’s planted on. They also share in the pain or gain if a particular field gets hailed out, for example, or produces a bumper crop. Through it all, each individual family owns their own land free and clear.

Today, the Pedersons crop 5,300 acres under this arrangement and it’s working very well.

“Because of our shared assets, we’re a viable operation,” said Terry. “Economies of scale have probably been the biggest benefit to the business.”

Good loves how the Pederson family has managed their business so that one farm can support four families without having to buy four sets of everything. “The business subsidizes individual land ownership,” he said. “They have separated the business from the land wealth and, in doing so, have created individual wealth for everyone.”

Good’s point is that land has to be dealt with, but sorting out the actual business structure of succession should come first—how all parties are going to receive income (salary for labour, management fees, return on equity, redemption of equity), how non-farming children are going to be recognized and how the parents are going to retire—then deal with the land itself.

Ideally, land transfer occurs over many years and is done in such a way that it accomplishes two things: first, allow the business to remain viable by protecting its main asset—the land—and second, ensure all parties are treated equitably. A non-farming sibling, for example, can gain income from land by means other than selling it.

In the Pedersons’ case, Harvey and Mildred have already started to will land to their sons and non-farming daughter, and liquidate assets they don’t need the income from anymore.

LEARNING TO BEND

Terry knows that the usefulness of the joint-venture structure can only go so far. Right now, only one member of the third generation, his son Brandon, is actively involved with the farm.

After a few years working for wages on the farm and demonstrating his commitment, he entered the joint venture (now called Pederson HBTRB) in 2010, assuming five per cent of the income and expenses, while Harvey went down to 35 per cent. And, per Harvey’s initial arrangements with his sons, Brandon was given use of everything owned by the joint venture prior to his coming on board, but assumed his 5 per cent responsibility on everything purchased afterward, from seed to combines.

There are other grandchildren who may or may not eventually come home to farm. “We do know that, in time, this joint venture will need to be split,” said Terry. “As these kids get older, we can think about what we need to get in place now to allow this to happen. We need a succession plan for the joint venture.”

That kind of thinking is exactly what Froese would like to see from more farm families. “The upside of doing the hard work of succession planning is the complete relief and the joy in knowing this farm will continue to thrive,” she said. “When that happens, there’s no more distracted management; you can focus on the business. And you’re having fun because you’ve all figured it out together.”

There is no one right way to build an effective farm succession process, because just about everything depends on a family’s particular structure: who wants to continue farming, who does not, and the willingness and openness of the individuals involved.

That means for a succession process to work, egos must be checked at the door.

Konschuh fully realizes what she is asking her parents to do—give up a piece of their autonomy and change their retirement path so that she and her partner can get a foothold in farming.

“Allowing someone into your process can be challenging,” she said. “You have to be open to possibility and other ways of thinking. What one person thinks is a great idea might not be what another person thinks. There are many ways to achieve a goal—it’s a complicated intermix of family and business.”

It comes down to what kind of relationships you want to build and maintain with your family members who also happen to be your business partners.

“Respect really has to be in there,” said Terry Pederson. “And we’ve all missed on that sometimes. We’re not always going to agree, but if you have to get your way all the time, don’t do it. You have to have the willingness to do this for the betterment of the family, for the business and for yourself.”

Comments