CARBON CONUNDRUM

DEBATE CONTINUES OVER THE MERITS OF ALBERTA’S AGRICULTURAL OFFSETS MARKET

BY KELSEY JOHNSON

In 2007, amid growing pressure to address mounting concern around climate change, the Alberta government created a system of agricultural carbon offsets designed to help farmers voluntarily lower their carbon footprint. The offsets were included as part of a broad government response to Alberta’s contribution to climate change, with the goal of reducing emissions from the province’s high-polluters, including oil and gas.

Yet, nearly 10 years later, questions about the system’s effectiveness remain.

The system works like this: producers who reduce carbon emissions through various government-approved practices—like no-till farming and biodigesters—are eligible for a carbon credit that can be traded on a provincial carbon market.

“I tell farmers it’s basically just another market,” said Paul Jungnitsch, a carbon offset agrologist with Alberta Agriculture and Forestry. “It’s an environmental market, so it’s different from selling grain or dairy or whatever, but really it’s just another market.”

Third-party aggregators are tasked with collecting the necessary paperwork and assist with the sale of the credits, with a set price maximum of $15 per tonne. Large companies whose emission levels are regulated by the province are then able to purchase those credits as a means of counteracting their own emitter status. The province made it a requirement that the offset credits be Alberta-made.

“What the offset system does is it allows the smaller players that also contribute to reducing the carbon emissions total to contribute, and they can sometimes reduce carbon by a cheaper cost,” Jungnitsch explained. “So, what it gives them is one more option in the big, grand scheme of reducing Alberta’s carbon emissions.”

The system is the first of its kind, Jungnitsch said—developed at a time when Alberta was facing sharp criticism internationally for its contributions to global climate change. “It’s a fairly newish thing,” he said, noting it’s the only one in Canada.

At first there were only two eligible programs: the biogas offset (which generally encompasses biodigesters) and the energy efficiency credit. As the system developed, more were added, including a conservation cropping protocol made available to farmers who engage in no-till or low-till practices on their farms.

The Alberta conservation cropping protocol defines no-till farming as “the use of openers and other land-disturbing implements for only one pass with a medium-disturbance opener (up to 46 per cent) or two passes with a low-disturbance opener (up to 38 per cent) with any crop cycle.” Under the protocol, landowners are also allowed to use discretionary tilling on up to 10 per cent of the land on a site.

To ensure emissions are actually being reduced, the province requires producers and aggregators to provide a mix of records specific to each program. Those records include proof of crop grown, proof of equipment used, identification of field location and size and GPS data.

“Carbon in the ground, it’s basically your root material and so on and so forth,” Jungnitsch explained. “It’s really hard to actually measure how much exactly is in the ground. It’s very, very expensive.”

Instead, he said, the government researched various agriculture methods—be it around seeding technique or livestock management—that could reduce emissions. Alberta was also divided into two zones, northern and southern, to take into account various environmental conditions that could affect the amount of carbon generated.

Jungnitsch said producers don’t have to show how much their emissions have been reduced, but they do have to prove that they are using the correct ecological practices.

Today there are 11 offset protocols available to farmers, including several aimed specifically at livestock producers in both the dairy and beef sectors.

Alberta Agriculture and Forestry estimates nearly 11 million tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions “have been voluntarily removed from the atmosphere by improving agricultural management.” A department brochure equates it to removing two million cars from the province’s roads.

Yet, according to Jungnitsch, the only offsets that have really been claimed are the ones for biogas and conservation cropping, with the latter accounting for nearly 40 per cent of all credits awarded. The slow uptake, he said, is in large part because of growing pains in the beginning, including issues with aggregators, and the fact that there’s not a lot of income in the system right now at the current carbon price.

The limited income generated is a complaint among producers, and one that Rich Smith, executive director of Alberta Beef Producers, said he’s heard before. “There’s not a lot of money in them, you know, because you need to work through an aggregator and, by the time all [the aggregator’s] money is taken away, there’s not a lot of money,” he said.

Kevin Auch, vice-chair of the Alberta Wheat Commission, agrees. He applied for the offset in the beginning, when it was retroactive. He said it took him a week to gather the required paperwork. He hasn’t applied for the credit since.

“I’ve looked into it since, but it’s a pretty small amount every year and it’s like, well, is this really worth it?” Auch said. He started doing no-till on his farm in the 1990s, long before the offset program was even in place, because it made sense business-wise.

“Basically [no till] helps me increase my production and reduce my costs,” Auch, who seeds about 5,000 acres annually on his farm near Carmangay, AB, explained.

Humphrey Banack, second vice-president of the Alberta Federation of Agriculture, has also heard the complaints around low revenue generation. He farms 4,500 acres near Round Hill, AB.

Part of those complaints comes from the fact that “the first payments [for cropping] were made retroactively for a number of years. They were bigger, so a lot of producers got into that,” Banack explained. “Now that they’ve gone down to annual payments, a lot of producers just backed away and said ‘It’s one less thing for me to do,’”

Increasing the value of the carbon credits, Banack said, should encourage more producers to participate. The Alberta government under Premier Rachel Notley has promised to phase in higher carbon prices—a promise initiated in June.

Still, farmers shouldn’t look at this as a major revenue generator, Banack explained. “You’re not going to get enough money out of here to build your retirement.” Instead, he said, farmers should regard the system as a form of recognition that agriculture is doing its part to benefit the environment and the country.

Banack has used the conservation cropping credit in the past, but said he stopped after running into issues with his aggregator. He said he intends to resume using the credit, but simply hasn’t gotten around to it yet. “It’s one of the things that’s on my list of things to get done,” he said. “For us it would be about a $1,500 to $2,000 payment every year. So, if you figure out my time—it takes me about 10 hours to do it—I’m making enough money to do it. I should be doing it.”

The Alberta government insists the offset system was never intended to be a get-rich-quick scheme. “It’s not a government support program, it is a market instrument,” the Alberta Agriculture and Forestry website reads, adding, “The system presents new ways for producers to consistently improve their operations and earn some extra dollars along the way.”

Still, the lack of income isn’t the only complaint about the offset system. Criticisms have surfaced on the beef side, too, where some in the industry say the current system simply does not work the way it was intended to.

“What I’ve heard from producers is that it is difficult to get verified that you’re meeting the criteria,” Smith said.

“I did a presentation to the province’s climate change panel on behalf of the livestock sector, and I made that comment about the beef offsets, and an aggregator who was in attendance was a lot more blunt than me,” Smith recalled. “He said, ‘The beef offsets don’t work.’”

Smith added, “It hasn’t been very relevant to beef producers.”

The government was redeveloping the beef offsets, Smith said, but the outcome of that work was dependent on findings of a provincial Climate Change Advisory Panel, struck in August by Environment Minister Shannon Phillips.

The panel released its findings and recommendations November 22. A government spokesperson has confirmed the review of the beef offsets program is still ongoing.

There are also issues around sustainability practices that aren’t recognized under the current offset program, Smith said, such as grassland conservation and forage production, both of which have been found to contribute significantly to carbon sequestration.

“By being able to raise food on those grasslands, we’re avoiding the other way to make food on those lands, which would be to plough up those grasslands and try and grow crops on them,” Smith said. “They [the government] are not giving you credit for what you’ve done already, which is encourage grass growth and not plough it up.” Alberta is home to some 50 million acres of agricultural land, of which 28 million are range, tamed pasture or forage land.

Producers aren’t the only ones complaining about the system either. Alberta’s auditor general has also fiercely and repeatedly criticized the offset protocol. In an October 2009 report looking into Alberta’s response to climate change, then-auditor general Fred J. Dunn said Alberta’s Environment Department needed to “strengthen its offset guidance and put a process in place to ensure the Alberta Emissions Offset Registry performs the work the Department needs.”

The government, Dunn said, also needed to “assess the risk of offsets applied in Alberta having been used elsewhere in the world,” and develop a means to ensure “the offsets used for compliance are valid.”

The types of records being used as proof of practice—particularly for the retroactive conservation cropping protocol—were inadequate, Dunn said. “In our opinion, the level of evidence defined as acceptable by the Department falls below that which is necessary to provide assurances that the offset credits actually existed,” his report reads.

Those criticisms returned in 2011, in a followup audit by auditor general Merwan Saher and his team. Again, the auditor general said evidence collected by aggregators on behalf of the Environment Department was insufficient.

“The [tillage] protocol allows a certain number of passes and width of equipment openers for both no-till and reduced-till practices,” the report reads. “None of the evidence the verifiers collected to verify individual offset claims was sufficient to prove the number of passes or the width of equipment openers used.”

Saher also raised concerns about the future fairness of the offsets system. “Without ensuring that all protocols conform to the same standards for protocol development, the Department cannot ensure that it provides a level playing field for offset project developers,” the report reads.

Still, despite all the criticism, Jungnitsch insisted the offsets market is “something to watch for and seems to be an up and coming thing”—a message he’s repeatedly passed on to producers. “The offset has always been part of a much bigger pollution-control picture,” he said.

Conversations around climate change are not new to Alberta, where the province’s carbon footprint has routinely dominated headlines and sparked more than a few criticisms from environmentalists around the world.

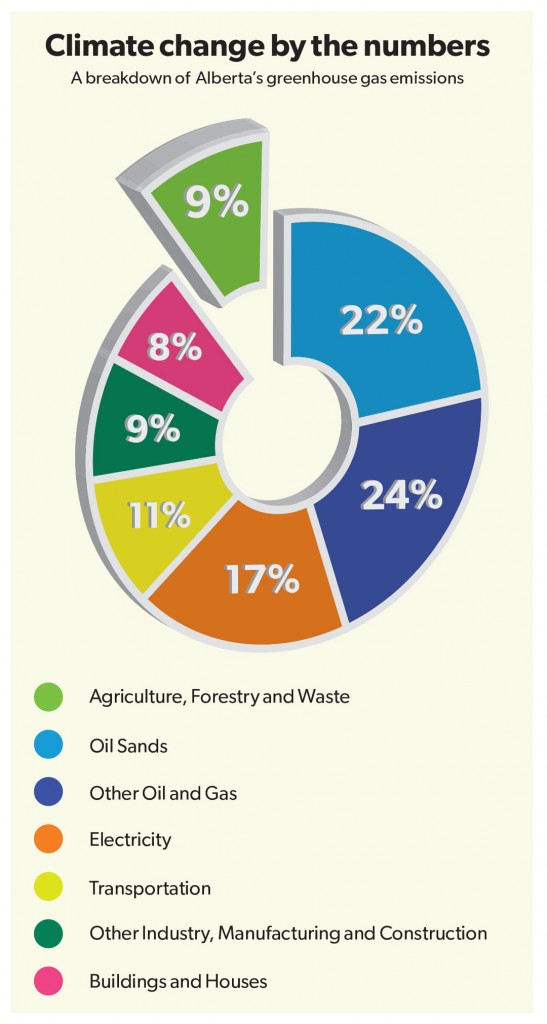

Alberta produces 37 per cent of all Canadian emissions, or 267 megatonnes, the majority of which are produced in the energy and gas sector. Statistics Canada estimates that number will be even higher by 2020, with Alberta responsible for 39 per cent of the country’s emissions.

Environment Minister Shannon Phillips has repeatedly insisted the province’s economic future is dependent on an Alberta-made climate strategy. “The future of Alberta’s energy economy depends on getting this right,” she wrote in an August 2015 discussion document. “The old approach of talk without meaningful action has not worked. Doing more of the same would be the worst thing we could do for our environment and our economy.”

Yet, the energy sector isn’t the only industry to be targeted by the international community for its environmental footprint. Agriculture, too, has been put under the microscope.

Globally, agriculture is the third-largest contributor to global greenhouse gas emissions by sector—behind only power generated by fossil fuels and transportation. Most of those emissions come from deforestation, Smith said, which isn’t a large issue in Alberta. “In fact, we have forests encroaching on our pastures,” he said.

According to Alberta Agriculture and Forestry, agriculture accounts for nine per cent (a total of 22 megatonnes) of all emissions produced in the province. Of that, nearly 50 per cent comes from cattle via methane produced during digestion. Nitrous oxide, from fertilizer, manure management and tillage, accounts for another 30 per cent.

Still, despite their relatively small emissions total, the Alberta government sees both agriculture and forestry as industries where greenhouse gas production can be reduced, largely because of sequestration options.

Then there’s the shifting global conversation on global warming and the environment, which is dominating political discussions at the local, provincial, federal and international levels.

“Whatever your view on climate change, it’s clear the world is looking for ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and that is driving new initiatives around the globe,” the Alberta Agriculture and Forestry website reads. “Alberta is taking steps to do its part and in fact is helping to lead the way.”

One of those steps included the creation of the five-member Climate Change Advisory Panel, chaired by University of Alberta associate professor Andrew Leach. It was tasked with reviewing Alberta’s current climate change policies, engaging with Albertans on the subject via public meetings and providing advice “on a comprehensive set of measures to reduce green house gas emissions.” Hearings took place last summer and fall, with several agriculture stakeholders from the livestock and crops sectors invited to take part.

Among the Panel’s recommendations was the adoption of a broad-based, economy wide carbon price, capped at $30 per tonne by 2018. The province, the panel urged, must also phase out its dependency on coal-powered electricity by 2030, and reduce methane emissions from oil and gas by 45 per cent. Purple gas and purple diesel are exempt from the proposed carbon tax plan, officials have confirmed.

Going forward, both Banack and Smith insist it is imperative that the government continues to recognize agriculture’s environmental stewardship.

“We’ve made significant improvements in the efficiency of our production; that, in turn, has reduced our emissions,” Smith said. “As we raise cattle more efficiently, there’s been a reduction in our greenhouse gas production.”

Banack agrees. “That’s the bigger thing here, the recognition—the recognition that we’re doing the right thing for both our farms and for the environment.”

Comments