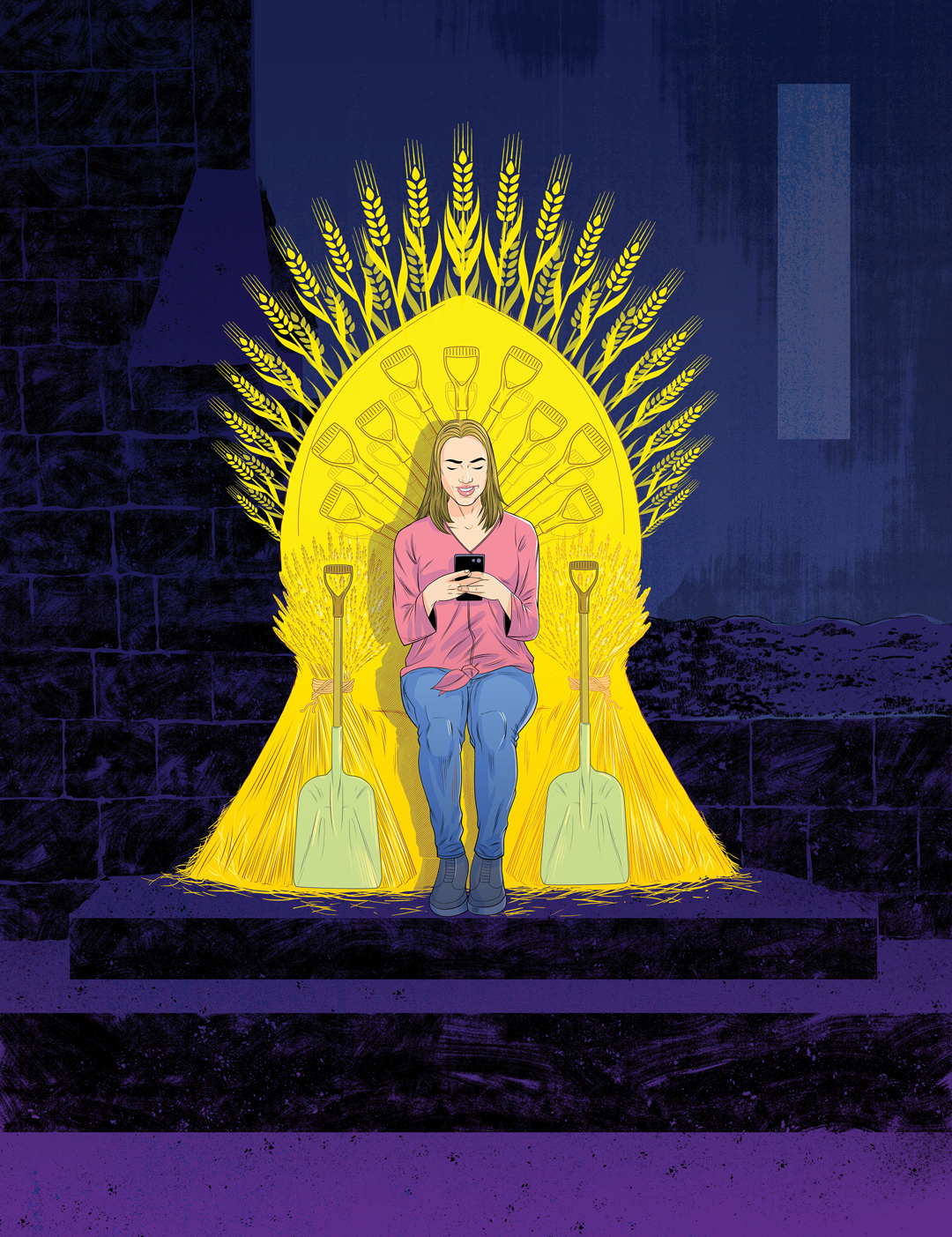

CO-OPPORTUNITY

CONDITIONS COULD BE RIGHT FOR A RETURN OF FARMER-OWNED GRAIN COMPANIES TO THE PRAIRIES

BY LEE HART

Over the past century, we have seen the rise and subsequent fall of a western Canadian grain handling system run by co-operatives—its fall due in some measure to management mistakes. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t opportunity for a farmer-owned grain company to once again flourish on the Canadian Prairies, according to business experts.

There is nothing inherently wrong with the co-operative model, according to academic and business leaders. In fact, there are several examples of successful, multibillion-dollar businesses in Canada and the United States operated by member-owned co-ops.

As Glencore PLC—one of the world’s largest globally diversified natural resource companies—suggested in a statement to shareholders in late 2015, it might sell off some of the assets from its Canadian grain handling company, Viterra. If so, is there opportunity for a farmer-owned co-operative to get back into the Canadian grain business?

The answer to that question varies from a solid “yes” to a more conditional “maybe,” depending on the school of thought.

A co-operative could definitely manage a Canadian grain handling company, said longtime business professor Murray Fulton, director (currently on sabbatical) of the Centre for the Study of Co-operatives at the University of Saskatchewan. Meanwhile, Milton Boyd, a professor and agricultural economist at the University of Manitoba, said there are several big “ifs” to overcome, and he isn’t sure if the political mindset is there to support a co-operative in the 21st century.

The Canadian grain industry was largely run by farmer-owned co-operatives from 1911 to the 1990s, said Gary Storey, a retired University of Saskatchewan ag economics professor. The dominant players for many years were four separate co-operatives: the Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba wheat pools, and United Grain Growers.

In 1998, the Alberta Wheat Pool and Manitoba Pool Elevators merged to form Agricore Cooperative Ltd. In 2001, United Grain Growers combined its business operations with Agricore Cooperative Ltd. to form Agricore United, a publicly traded company.

Meanwhile, the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool (SWP) carried out a massive expansion phase after listing its shares on the Toronto Stock Exchange in 1996—a strategy that nearly drove the co-operative into bankruptcy. A new CEO, Mayo Schmidt, was hired in 2000 to get the company back on track with a restructuring and refinancing program that was initiated in 2003. He eventually led the Pool to become a federal corporation under the Canada Business Corporations Act in 2005, ending its co-operative status.

In 2007, the SWP won a bidding war against James Richardson International to take over Agricore United, creating a new company called Viterra Inc. Six years later, commodity giant Glencore PLC struck a $6.1-billion deal to buy Viterra. Now, Glencore might sell some of Viterra’s assets in an effort to reduce company debt, but there have been no new developments since last fall.

HOW THE CO-OPERATIVES STARTED

In recounting the history of grain elevators in a chapter for the online Saskatchewan Encyclopedia (esask.uregina.ca), Storey explains that, from the late 1800s to 1910, Canadian grains were handled and marketed by numerous private Canadian, U.S. and European companies.

According to Storey, “In the period leading to 1910, the early elevator business was represented by flour-milling companies with head offices outside of the Prairies … “When the Canadian Northern Railway was opened in 1900, interest in elevator construction was spurred. The British-American Company was consequently formed in 1906; the U.S.-based Searle Grain Company also entered the Canadian market and operated on Northern Railway lines; and in 1909 the Peavey interests of Minneapolis formed the National Grain Company, which operated on CPR lines. Many other companies were formed and also entered the elevator business, such as Alberta Pacific Grain Company, Pioneer Grain Company, Norris Grain Company, British Co-operative Wholesale Society, Scottish Co-operative Wholesale Grain Company, Parrish and Heimbecker, McCabe Brothers Grain Company and N.M. Paterson and Sons.”

But as these companies and their elevators appeared on the Canadian Prairies, pioneering farmers grew increasingly discontented with business practices of “line elevator companies,” Storey writes. The companies were often referred to as the “syndicate of syndicates” for their alleged collusive practices in fixing prices.

Fearing a private monopoly, farmers petitioned the federal government to take over the grain terminals and provincial governments to take over all grain elevators.

“Although governments resisted this policy, there were exceptions,” said Storey. “The government of Manitoba, for example, purchased a number of primary country elevators in 1910, which proved to be unprofitable.”

While governments wouldn’t act, farmers decided to take action on their own. In 1899, there were 26 farmer-owned elevators on the Prairies, although they all struggled to some degree. The first major farmer action came in 1906 with the formation of the Grain Growers’ Grain Company in Saskatchewan. Support from the Saskatchewan government for the concept of farmer-owned-and-operated elevators eventually led to the formation of the Saskatchewan Co-operative Elevator Company. A similar path was followed in Alberta with the creation of the Alberta Farmers’ Co-operative Elevator Company, which eventually merged with the Grain Growers’ Grain Company in 1917 to form United Grain Growers. The Saskatchewan co-op remained independent.

These early co-operatives were looking for a way to collectively market their grain. In the early 1920s, farmers across the Prairies created the Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta Wheat Producers Ltd., and that company formed the Central Selling Agency. The three provincial groups became known as the Wheat Pools, and each set up a fund to build its own elevators. The SWP took over its predecessor, the Saskatchewan Co-operative Elevator Company, in 1926. Thanks to an aggressive buying and building program, the three Pools grew from just 100 owned elevators in 1925-26 to 658 elevators in 1927.

The Pools and their Central Selling Agency were successful for several years during the 1920s. Through pooling accounts, farmers received the same price regardless of the time of year they sold their grain. All ran well until farmers reaped a poor-quality wheat crop in 1928 and grain prices began to fall in 1929. With the Pools running into financial difficulty, the federal government stepped in to dissolve the Central Selling Agency and create the Canadian Wheat Board (CWB).

With the CWB marketing wheat, the three Pools and United Grain Growers operated as farmer-owned grain handling companies.

WHAT CAN GO WRONG?

While all the Canadian Prairie grain handling co-operatives went through business structure changes starting in the 1990s, Fulton points to the example of the SWP to explain what can go wrong with co-operative management. In a paper on the restructuring of the SWP prepared for the Journal of Cooperatives, Fulton said that if the board of directors isn’t paying close attention it can lose control of management, and that’s when mistakes are made. Expansion plans can be excessive, including paying too much for new acquisitions.

“From 1996 to 1999, the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool invested in approximately 25 acquisitions and long-term debt grew five-fold. This spending stemmed from a belief of urgency,” Fulton said.

Under the direction of CEO Don Loewen and executive vice-president Bruce Johnson, SWP embarked on “Project Horizon,” a massive rebuild of its elevator network in 1997 with the construction of 22 inland terminals at a cost of $270 million. The company also made ill-fated investments in Poland and Mexico. While Project Horizon gave SWP the most modern handling network in Western Canada, the crushing debt load and a share price that tumbled from a peak of $24.40 to a low of $0.20 left the once powerful company teetering on the brink of bankruptcy by 2003 and then again in 2005.

The Pool believed that it needed to “move rapidly to beat the U.S.” and it needed to “become more of a global player and expand beyond Saskatchewan borders.”

There was a conviction that if the Pool did not “stay at a significant size … it would become one of two things: irrelevant or sucked up.” Interviewees recalled how Pool management and board members arrogantly believed the Pool could become “the ConAgra of the North” and become “one of four or five top grain companies in the world.”

“In short, SWP succumbed to the two classic problems associated with financial investment activity, agency (board/manager control) problems and management overconfidence. The result was as expected—the Pool overinvested and made poor investments, the consequence of which was that its financial viability was severely challenged. What started as an attempt to keep the SWP competitive in a rapidly changing market ended with SWP making bad business decisions, which in turn resulted in the loss of the Pool’s co-operative structure.”

CO-OPERATIVE OUTLOOK

Learning from the lessons of the SWP and other co-operatives around the world, Fulton said he still has faith in the co-operative system.

“I personally think there is still a role for a farmer-owned grain handling co-op in Canada,” he said. “Grain handling co-ops play a very important role in the United States—in fact, it could be argued that they are now the dominant player at the grain handling level. And some of them are very large. Minneapolis-St. Paul-based CHS is a $44-billion business. Its members and affiliates throughout the Great Plains (these are local grain handlers and suppliers of fertilizers and chemicals) are also very large.

“Thus co-ops can and do operate on a very large scale. A number of authors have argued that traditional co-ops have to change—they cannot operate on the scale required with what might be called the standard co-op structure. However, there does not appear to be any one single model for this alternative structure.

“In the United States, for example, co-ops have evolved in a number of different ways. Nor is there any requirement that they have to move to an investor-owned (or publicly traded) model—again, the experience in the United States is that co-ops have remained strong as co-operatives.”

Similarly, some of Fulton’s colleagues at the Centre for the Study of Co-operatives agree that co-operatives can be a very effective model for large or small businesses, although they do face challenges.

“As the business or the co-operative gets bigger and more complicated, it becomes a test of their governance,” said Brett Fairbairn, acting director at the Centre. “We’re seeing today where these co-operatives are managed by boards of directors of experienced farmers who are well educated and trained in leadership. What can this group of well-trained farmers bring to the table?

“There are many good features of co-operatives as well as weaknesses. And the one main weakness we saw in the Canadian Prairie grain co-ops was the ability of the board to give direction and control management.”

Eric Micheels, an assistant professor in business and economics at the University of Saskatchewan, said one feature of the farmer-owned co-operative is the capacity for more “patience capital.”

“With a publicly traded company, to some extent the pressure is on to return dividends to the shareholders,” Micheels said. “Whereas with a co-operative, as long as the investment meets the goals of the co-operative, it can probably be a bit more patient for the investment to pay off. The board may be willing to wait a bit longer for the returns rather than need that quick hit on returns.”

While there are successful agricultural co-operatives in Western Canada, such as Federated Co-ops, American co-operative CHS Inc., which is establishing retail outlets in Canada, has developed a diversified multinational business over its 85-year history.

It is all about providing good value and service to member-owners, as well as returns over the long haul, said Lynden Johnson, CHS executive vice-president, country operations.

“In the agriculture industry it is very difficult to get that quick return on a quarterly basis as is often demanded by publicly traded companies,” Johnson said. “Our owners are farmers—family farms. They know they are getting value and service, and they know in the cyclical world of agriculture the returns are there over the longer term. And that’s the advantage the co-operative has. We are owned by the people who use us. We are not owned by Wall Street. We are not owned by investors who only care about a quarterly return. We need to provide value and service in the long-term rationale, looking at how our producers can be successful.”

CHS is a co-operative formed through the 1998 merger of two other large co-operatives: Cenex, which focused on energy and agronomic services, and Harvest States, which focused on the grain side of the industry. The co-operative serves 1,300 local co-operatives in 26 states and directly serves 85,000 producer members.

Johnson said CHS’s success is built on providing value and service to its members, as well as its grassroots governance system. A board of directors locally governs each CHS outlet, or business unit of several outlets.

“We have anywhere from one to 15 outlets in a business unit, depending on the geographic area, that has local governance,” Johnson said. “The local board is able to provide direction to the co-operative concerning the markets and the needs of farmers in that local area. In Illinois it may be a corn-growing area, whereas in Montana it might be a beef-producing area, so each board of directors is responsive to the needs of farmers in those areas. We are accountable to the member-owners to provide value and service as well as a return on investment, which is returned back to members in the form of patronage payments.”

Back on the Canadian front, Milton Boyd at the University of Manitoba said he isn’t sure if Prairie farmers are willing to or interested in giving co-operatives another chance.

“As the co-operative model and management began to decline over the years and leave farmers less satisfied, many of the larger and more progressive grain farmers took their business to private firms, creating even more difficulty for the co-operatives and leading to more decline,” Boyd said.

“For Sask Pool, some older farmers who had dividends owed took Sask Pool shares as payment because Sask Pool wanted to preserve cash, only to see Sask Pool make a lot of poor decisions and poor investments, and pile on excessive debt. Sask Pool went near bankruptcy, and some farmers lost nearly all their stock value, became upset, and took their business elsewhere as a result.

“Historically, co-operatives arose many years ago at a time when farmers were at more of a disadvantage, and were to serve as a countervailing power to offset the alleged excessive market power of private firms. Grain companies, banks and railroads didn’t face enough competition, and farms were smaller, [and farmers were] less independent, less educated and less informed, and could be taken advantage of on price as they had poor price information. And some likely didn’t even have electricity, telephone or radio, and [had] horses and trail instead of trucks and highway.

“Today, Farm Credit Canada and credit unions have helped provide competition to banks. Farmers now have highway trucks and can haul long distance—that has helped some with transportation competition, and brought some more competition between grain companies. Today, with Internet, smartphones and better price information, farmers are better educated and informed. With large, modern trucks they can now carry their grain long distances within Canada, or to the U.S. markets, for example, if needed.

“So as long as government can ensure sufficient competition and efficiency in the grain industry, there is less need for co-operatives to arise and provide competition and countervailing power.”

From a farmer perspective, Kent Erickson, who farms at Irma, AB, said the key element for him in grain company ownership is having a competitive industry.

“Whether it is a publicly traded company or a co-operative, what I want to see as a farmer is more competition in the industry,” Erickson said. “I think farmers get concerned when they see a concentration of company outlets, with reduced choice or options. We want to see an industry where the company assets are spread out so a producer does have a choice. More competition is healthy.”

Erickson said the concept of a farmer-owned co-operative returning to the grain handling industry has potential, although he isn’t sure if a new co-operative can manage the financing to be a player today.

“It might be easier today to manage a co-operative simply because there aren’t as many small farms as there was years ago,” Erickson said. “A co-operative needs to serve all size of farms—I consider my own as a small to medium-size operation—but it might be simpler today simply because there aren’t as many farmers. I believe there is also much more business sense out there today to better manage co-operatives. I can see potential for 20 to 30 farmers to form a co-operative to operate a particular facility, but if the group is buying assets from a large company, that company may not be interested in selling individual locations, so then it becomes a challenge to raise the capital for a larger investment.”

Comments