AN AGTECH PIONEER

BY LEE HART • PHOTOS BY ZOLTAN VARADI • ARCHIVAL IMAGES COURTESY OF GLENBOW ARCHIVES’ UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY LIBRARIES AND CULTURAL RESOURCES DIGITAL COLLECTIONS

Over seven-plus decades, Alberta farmer Charles Sherwood Noble developed and promoted new farming practices and technical innovations. Of these, the Noble blade cultivator was used around the world as a low soil disturbance weed control tool. For his work, he was named a Member of the Order of the British Empire in 1943.

Noble was among a number of Alberta farmers who set out to improve soil conservation at the turn of the 20th century. Fearless in his pursuit of agronomic innovation and the prevention of soil erosion, he earned a central place in the history book of western Canadian agriculture.

FROM BAREFOOT PLOWMAN TO EQUIPMENT MANUFACTURER

Born in State Center, Iowa, in 1873, Noble left school when he was 15 to help his widower father raise his five younger brothers. He established his own farm at Knox, North Dakota, in 1896, later leaving it to homestead near Claresholm in 1902. Reportedly, he was seen breaking land in his bare feet behind a plow pulled by three oxen and a horse.

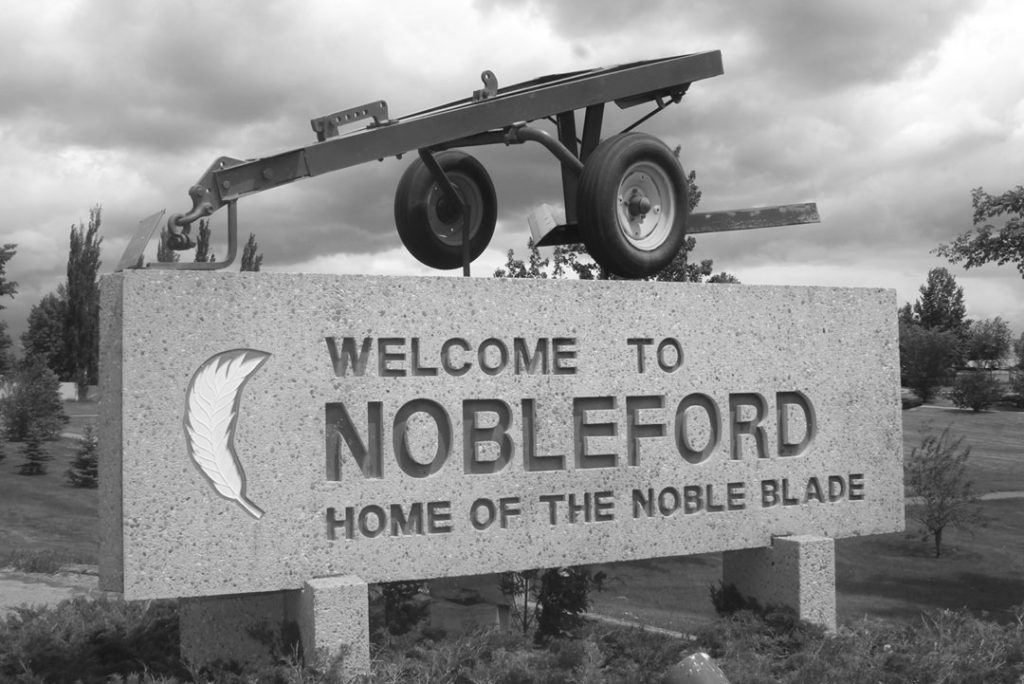

From this humble start, he relocated north of Lethbridge and over the following dozen years assembled the largest farming operation of its day in the British Empire. He farmed about 36,000 acres using as many as 600 horses until steam, and later gas-powered machinery, came on the scene. His farm headquarters grew and later became the village of Nobleford.

The impressive farm was hit by falling grain prices and drought conditions that produced successive poor crops. The downturn caused lenders to foreclose on a $600,000 debt. Bankrupt but undeterred, the resourceful Noble rebuilt his business over a handful of years. By 1930 he again farmed about 8,000 acres—still a good-sized operation even by today’s standards.

Throughout much of his farming career, Noble championed soil conservation. According to author Grant MacEwan in his book Charles Noble: Guardian of the Soil, Noble observed the impact of soil loss due to wind erosion in the Dakotas around 1900 and later in southern Alberta during the severe drought years of 1910, 1918 and 1919.

In the early 1900s, tillage was common practice on North American farms. “For generations the plow was the symbol of farming. Good plowing was good farming and good farming was good plowing,” wrote MacEwan. In the absence of herbicides, plowing was necessary to control weeds. Farmers also preferred the tidy aesthetics of black dirt fields.

This preference was supported by certain leading agronomic advice of the day. This included people such as H.W. Campbell, a South Dakota farmer and author who promoted farming practices developed in England in the 1700s. In his widely read 1907 book entitled: The Soil Culture Manual, Campbell promoted multiple tillage operations to produce “dust mulch” on the soil surface as a supposed method to conserve moisture. Noble himself had been a follower of what later proved to be faulty advice.

The dust storms Noble witnessed in his early farming days were a prelude to the drought years of the late 1920s and 1930s and prompted Noble to investigate conservation measures.

He discussed such initiatives and worked with fellow farmers and researchers at the Claresholm School of Agriculture and the Dominion Experimental Station, which later became the Lethbridge Research Centre. All believed in improving soil conservation and worked together to tailor practices. Collaborators included Rufus Bohannon of Sibbald who experimented with “plowless summerfallow.” He used a duckfoot cultivator and harrows to control weeds.

Fields looked messy, but the practice was somewhat effective in reducing wind erosion.

Noble also followed the field trials of farmers such as L.P. Tuff of Lethbridge and the Koole brothers of nearby Monarch who experimented with strip farming techniques to reduce soil loss by wind erosion. In his blacksmith shop, Noble developed one of the first rod weeders as a low-disturbance weed-control tool. None of these measures were perfect but all appeared to reduce soil loss.

Heading into the 1930s, drought conditions worsened and the Prairies experienced weather events known as black blizzards. “About the only farmers who were escaping the devastation of wind were those who were strip farming and those who seeded in stubble or on land that had been cultivated without loss of stubble,” wrote MacEwan. “It was silt from farms being cultivated by the old methods that was polluting the air and depressing the people.” Noble felt compelled to invent better ways and “better tools,” to protect the soil.

In 1935, at the age of 62, family members urged Noble to finally take a holiday, “especially after the dry and discouraging summer of 1935, and they prevailed upon him to visit California,” wrote MacEwan. During this trip he observed a farmer using a straight blade tool. It slid a few inches below the soil surface to loosen sugar beets for harvest. Noble envisioned a similar tool being used to control weeds while leaving stubble to protect the soil.

With the help of a California friend who owned a shop, the excited Noble found a nine-foot section of grader blade with which to build a prototype cultivation tool he soon hauled back to Nobleford. “[The] farm shop rang again with the clank of a smithy’s hammer as [Noble] with the help of Niels Kristofferson [one-time mayor of Nobleford], pounded out new blades and frames making each model a little better than the last one,” wrote MacEwan. Noble initially had no plans to enter the manufacturing business, but simply to develop equipment to be used on his farm.

Along with strip farming practices, the prototype straight blade tool worked well over the following two seasons. It controlled weeds and left stubble to protect the soil. Neighbours were impressed and asked Noble to build more of these tillage tools for them.

Noble made 50 blades in 1937. In June 2 of that year, the worst dust storm ever seen on the Prairies blew from Lethbridge to Regina. Already mounting calls to deal with soil erosion reached a new pitch.

Noble began the small-scale manufacture of his blade cultivator. Eventually the straight bar was replaced by a V-shaped blade. For light, sandy soil, a 75-degree blade could be used and a wider-angle 100-degree blade could handle firmer soil.

Demand for the cultivator soon outgrew the ability of Noble’s shop to produce them. A factory was built in Nobleford in 1941. It produced 125 cultivators that year and increased output to 200 in 1943. As manufacturing materials became available at the end of the Second World War, production jumped to 1,000 units in 1946. A larger factory was built in 1951 to meet demand in Canada and the U.S. The unit was later exported to Egypt, El Salvador, India, Iraq, Pakistan, Russia and South Africa.

Noble Cultivators Ltd. eventually diversified to produce hoe drills that could work through crop residue, chisel plows, packers and harrows. At one point, the company had 600 dealers in Canada and 17 states. The business remained family-owned until it was sold to Versatile Manufacturing in 1982.

A FARMER THROUGH AND THROUGH

“Development of the Noble blade was a significant step in soil conservation,” said Ben Ellert, a soil research scientist at the Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Lethbridge Research and Development Centre. Ellert recalls using a Noble blade cultivator to control weeds during his early years on the family farm at Milk River in the late 1970s. The tool was widely tested at research centres during the 1930s and 1940s and used in zero-till research projects even into the 1990s.

Henry Janzen is a semi-retired agricultural researcher in Lethbridge. He similarly said Noble developed an important link in early soil conservation efforts.

“Development of the Noble blade was a pivotal event,” said Janzen. “Charles Noble was among many who were horrified by severe soil erosion and worked hard to find a solution. The Noble blade was probably an important intermediate step between mold board plowing and no-till farming. It took a while to be adopted, but farmers came to appreciate the importance of keeping stubble on the soil surface.”

Noble would no doubt have been proud to know that certain conservation farming methods he and like-minded farmers pioneered remain in practices today.

Noble’s great-grandson Mike Noble was busy direct seeding canola on his farm northeast of Nobleford when GrainsWest spoke to him in early May.

With family members, he farms about 3,000 dryland acres as well as irrigated cropland. The family carries on the conservation farming practices of continuous cropping and direct seeding adopted by his late father Bryan Noble more than 30 years ago.

Mike never knew his great-grandfather who died in 1957 at the age of 84, but is certainly aware of his legacy as a champion of conservation farming methods. “Actually, from where I am seeding today, I can see some of the Noble blade cultivators that were once used on the farm,” said Mike. “I believe my great-grandfather had a huge impact on the conservation farming movement. He, along with others, led the way for zero-till farming. Some people note that C.S. Noble was only involved with tillage, but that was primarily an interim measure. He was interested in conservation farming and very forward thinking. He was always interested in what was next, looking for the next improvement.”

Noble’s grandson, also named Charles, now owns the two-storey house in Nobleford sometimes referred to as the Noble Mansion. Semi-retired from farming, he is also a writer and poet and enjoys spending time in the home’s comfortable den with books from its extensive library. He fondly recalls his namesake.

“We lived in the house across the street from the big house, but as kids we would come over to visit and my grandmother [Margaret] would serve us cookies,” said Charles. “My grandfather was quite an imposing figure, he was a tall man, 6’2”. He always enjoyed spending time with us and he had quite a sense of humour.

“He was a man who loved horses. He farmed with 600 head at one time, but he had his favourites. He’d often be up at 3 a.m, and head out to the barns to feed the horses. He used to farm with some huge hitches. He actually hated to see the horses replaced by steamers, but realized it was necessary.”

Charles said while many words can be used to describe his grandfather, “more than anything, he was a farmer through and through. He was a farmer committed to conservation farming practices. When he was around the factory, he was certainly a businessman. My dad and my uncle along with others always called him ‘the chief’ as he was always thinking and had a lot of drive,” said Charles.

“When he was out in the country and perhaps saw another farmer doing something he might not agree with, he would often stop and talk to them about conservation farming. He always promoted the idea of smaller farms, simply because he felt they were easier to manage properly and could adopt best management practices.

“Yes, he was an entrepreneur, a businessman and a good salesman, but it all involved promoting conservation farming,” said Charles. “Right to the very end he was concerned about protecting the soil.”

Comments