A TERRA FIRMA TALE

HOW GEOLOGY AND GEOGRAPHY SHAPED ALBERTA AGRICULTURE

BY TODD KRISTENSEN • PHOTO COURTESY OF PROVINCIAL ARCHIVES OF ALBERTA

The soils around us are not the soils that our grandfathers broke,” explained Darwin Anderson, a retired professor from the University of Saskatchewan who spent his career studying Prairie dirt in Western Canada. Anderson explained that soils are constantly changing. To understand how they took shape in Alberta requires a look back, not just at a century of family farming that altered soil productivity, but at millions of years of strange and powerful events. Modern farming in Alberta is based on a thin sliver of soil with a thick history.

The story of every field in Alberta begins over 180 million years ago when the province sat, smooth and flat, inside a geological plate that began slowly crashing into islands and belts of land to its west. The collision, which ended about 50 million years ago, lifted the mountains of B.C. and Alberta and tilted this province down to the east. Since then, sand, silt and gravel poured down the slopes and laid the bedrock basement beneath our rubber boots.

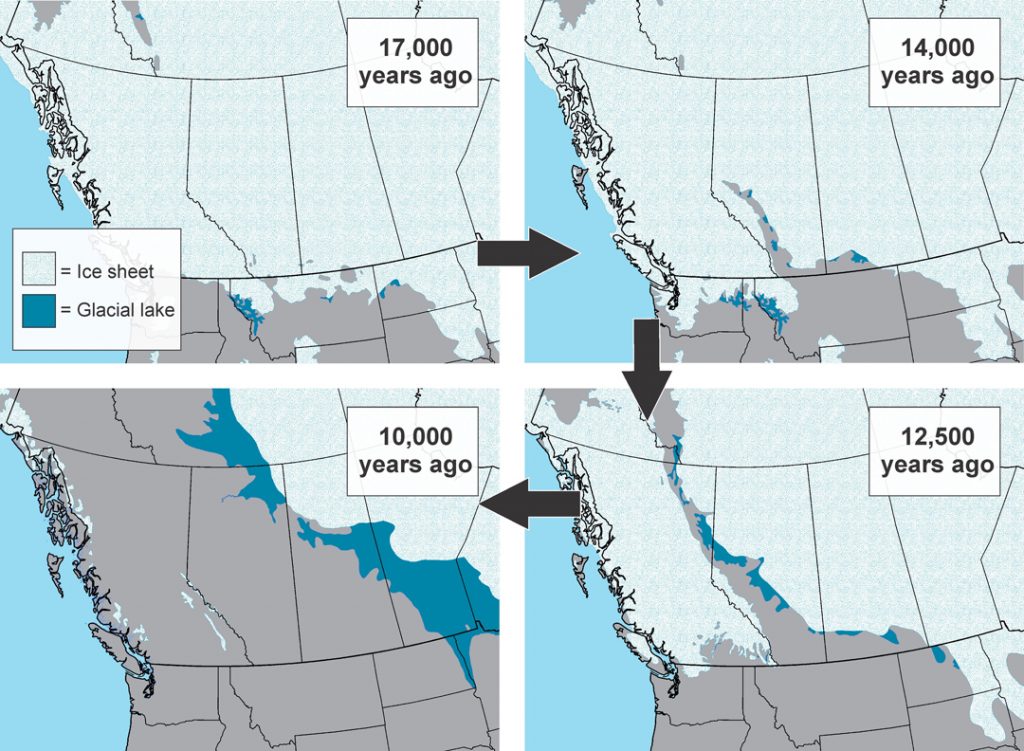

All was peaceful until two million years ago when ice sheets over one kilometre thick carved a new landscape. Nigel Atkinson of the Alberta Geological Survey likens these glacial forces to bulldozers that moved loads of rock across the province, cut out swaths, and smoothed the Prairies. Atkinson explained that most fields in Alberta owe their current shape to the legacy of ice or its meltwater. Importantly for modern agriculture, ice wiped away existing dirt and reset the soil formation clock to zero.

Unlike other regions of the globe, where soils that have been leached for millions of years, Alberta’s ground is a youthful 10,000 years old. The ice age produced fertile soils—growing glaciers were like a blender that chopped the compact bedrock of acidic shale and sandstone in with basic limestone to make a porous smoothie of sediment with a healthy pH.

Map by Todd Kristensen.

Ancient ice that covered Alberta melted to the west and east to create a hallway or ice-free corridor. For thousands of years, meltwater from the west delivered sediment to glacial lakes in this corridor that were dammed by ice to the east. Picture water flowing down a ditch to a blocked culvert. Large parts of the province were covered in a trapped water body larger than the Great Lakes where fine materials, such as clays and silts, dropped out. Such lake sediments make fertile soils because they retain moisture and bind minerals.

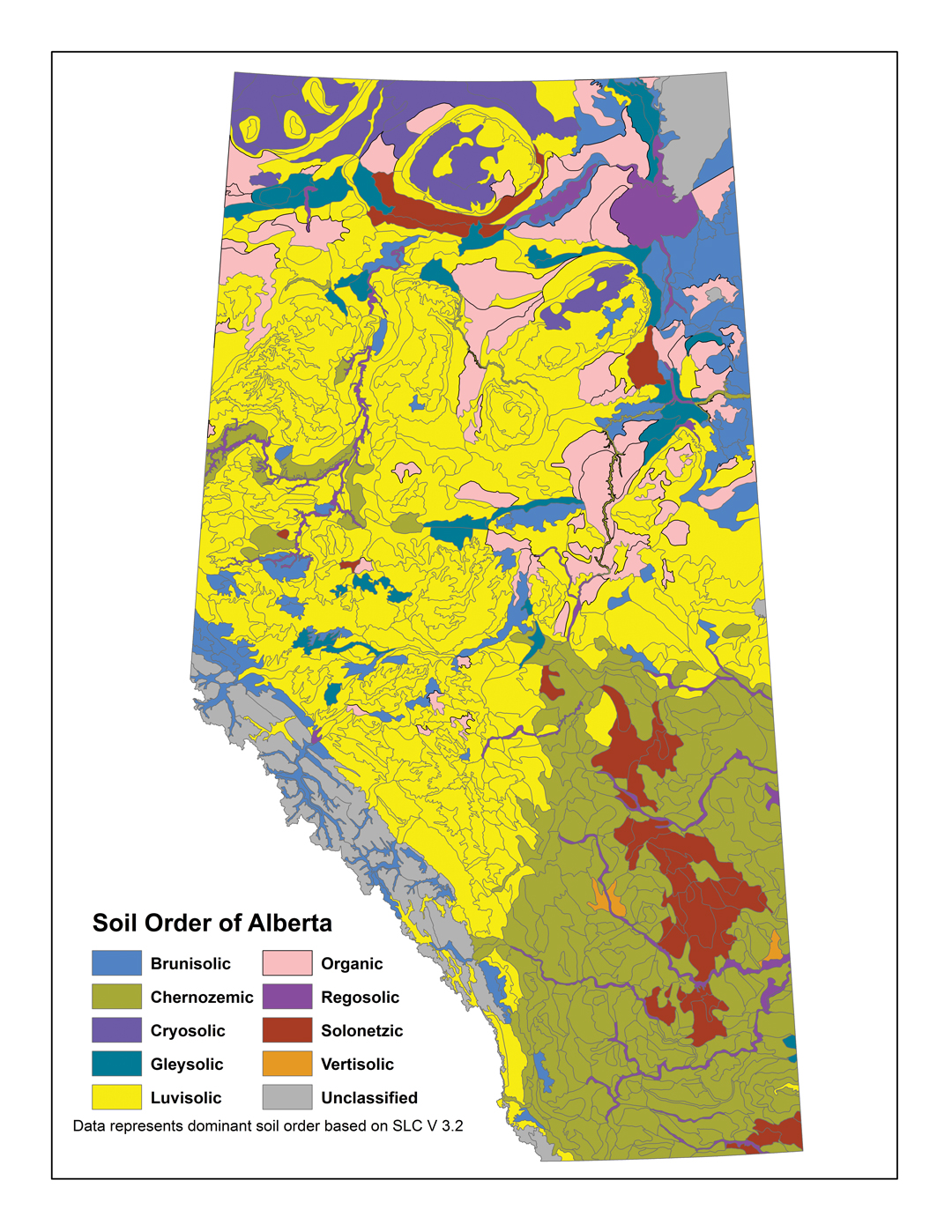

While mountains, ice and water provided the basic ingredients for modern soils, plants and microorganisms did the rest. Alberta has been divided into a patchwork of soil types known as orders by scientists such as Anderson, who noted that soils are the base for plants, which in turn build more soil. The two shape each other. Modern farm fields were altered for 10,000 years by two main types of plant environments. Forests in Alberta grew where moisture was high thanks to abundant rain, low summer evaporation and retention of water in winter, owing to its northern geography. Southern Alberta experiences a water deficit because it lies in the rain shadow of those ancient mountains that push warm and wet air from the Pacific Coast up where it cools, which causes it to drop most of its moisture west of the province. As well, high winds and hot temperatures combine to produce high rates of evaporation in the southern grasslands.

Map by Todd Kristensen.

Northern forests and southern Prairies make very different soils. Forests have big tree roots that break down slowly. The rest of the organic matter produced by trees and shrubs falls on top of the soil where much of it stays. On the other hand, grasses store most of their mass underground in small roots that break down quickly, which pumps organic matter below the surface. Prairie grasses produce rich black and brown chernozem soils while the central parkland and northern boreal forest produce grey luvisols. In the middle of Alberta’s Prairie region are large pockets of solonetzic soils. These are created where the parent rock is high in sodium and where ground water and evaporation are relatively high, which brings up salts from lower layers.

Len Leskiw has been mapping soils in Alberta for more than 40 years. “It’s in my DNA,” he said of the deep passion for soil science he developed as a farm kid. His consulting firm specializes in soil reclamation and conservation and he has worked with many land developers from Fort McMurray to Lethbridge. He said the province’s soils develop in harmony with climate. Northern latitudes have shorter growing seasons but more water, which favour cereals such as barley, oats and certain types of wheat. All of these can be cultivated annually given abundant ground water and healthy rains that pour onto dense luvisol soils where forest has been cleared.

Central and southern Alberta have longer growing seasons where, if rich chernozem soil occurs, the areas can support canola, wheat, rye, barley and oats and pulse crops that include dry peas and beans. But water is relatively scarce, so, in the past, fields had to be left fallow to recover moisture. Irrigation solved some of these problems and now the southern fields also support good forage yields, corn and vegetables such as beets and potatoes. Often called clay-pan soils, solonetzic soils are found in a similar climatic region to chernozems and support much of the same vegetation but the salts generally lower productivity. As an example of how soil type and geographic weather patterns come together, Alberta’s barley belt encompasses an arc of land extending approximately from Vermillion at its northeast to the foothills of the Rockies in the West with its northwest side taking in Lacombe and its southeast limit taking in Stettler and Drumheller. The area curls across the margin of the fertile chernozems and is bordered by more arid land (with solonetzic soil) to the east and south and by luvisols (with lower organic matter) and shorter growing seasons to the north and west.

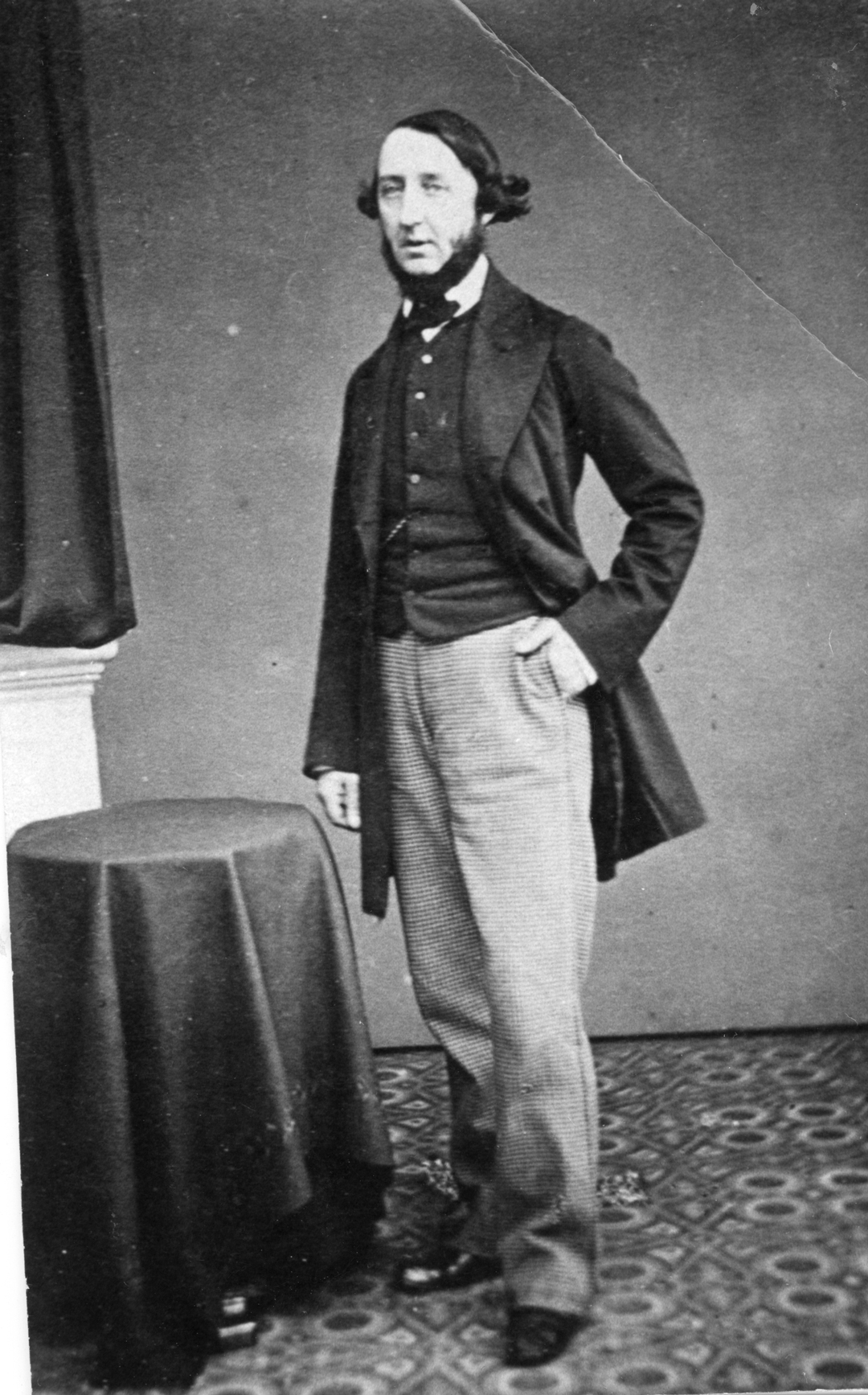

Captain John Palliser photo courtesy of Waterford County Museum, Dungarvan, Ireland and Sean Murphy.

As neat and tidy as soil maps of the province are, scientists recognize that local topography, like the rolling hummocks that the glaciers paved, create soil characteristics that vary by the acre. In 1857, the British-led expedition of Captain John Palliser assessed the agricultural potential of much of the Prairies. He famously deemed southeast Alberta and southwest Saskatchewan to be a near desert unfit for the plough. The area became known as Palliser’s Triangle. Bounded by the United States border, it extended from present-day Cardston and Calgary in the west almost to Lloydminster, SK in the north and encompassed Regina to the east. We now understand that this region is far from uniform and features a patchwork of soil types. New wheat varieties and irrigation would later turn these fields into some of the most productive in Alberta.

Alberta’s agricultural origins lie in a chain of events that began millions of years ago. Mountains made our bedrock and glaciers pulverized it. Plants then built various types of soil that now interact with mountain-driven climate to influence what crops can grow where. But the story of Alberta’s soil development has a few more curious chapters. Biologists call much of the province a “buffalo landscape” because millions of bison pounded the Prairies, grazed along its margins and stamped out the spread of trees and shrubs. They helped build North America’s chernozems.

For thousands of years, people burned grasslands and parklands in part to provide food for bison, as lush grass grows in recent burns. Early explorers in the province observed how First Nations controlled vegetation as their fires burned back the constantly advancing forests. The actions of buffalo, people and climate created the grasslands found through central Alberta and up to Peace River Country north of the well-named Grande Prairie and High Prairie.

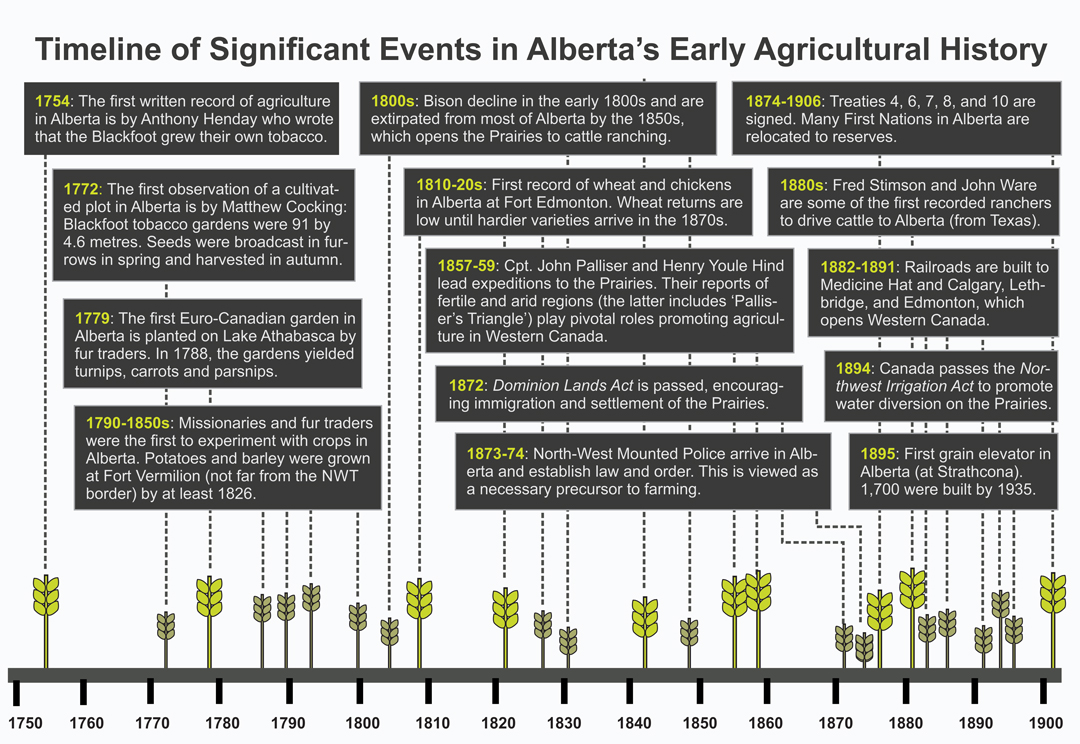

Grazing and burning helped produce the inviting grasslands that greeted Alberta’s early farmers. Blackfoot First Nations in Alberta farmed tobacco for several hundred years before Europeans arrived. Archaeological evidence also suggests corn may have been traded into Alberta centuries ago but domestic grains and cattle ranching didn’t arrive in the province until the 1800s.

Over-hunting to feed fur traders and settlers in the first half of the 1800s wiped out Alberta’s buffalo herds and opened the Prairies to cattle, while treaties in the second half of the 1800s forced many First Nations to relocate. This happened at about the same time as the Dominion Lands Act was passed by the federal government in 1872 to encourage homesteading in Western Canada. To help settle the West, national programs of railway construction pushed rails to Calgary (1882) and Edmonton (1891), which made it possible to move immigrants, livestock (including horses for ploughing), machinery (such as tractors and seed drills) and supplies. Large-scale irrigation began in the first decade of the 1900s. All of this contributed to an agriculture boom with major impacts on soil development.

In the early days, ground was ploughed up to 30 centimetres deep to improve water absorption, break up roots and recycle nutrients. Summer fallowing was also practiced to replenish moisture and nutrients. Winds, rain and drought did a number on the brokenup topsoil. In places, up to 13 centimetres of it blew away and crippled productivity. Contemporary studies show that up to 80 per cent of the organic matter in some chernozems disappeared in the first few decades of cultivation. “Tillage erosion” was also noted when soil was washed from hills and ridges into basins and wetlands. By 1926, 10,000 farms in Alberta were abandoned due to crop failure. Most of these occurred on solonetzic soils that responded poorly to drought.

Timeline by Todd Kristensen.

Allan Rowe is an historic places research officer for Alberta’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism and an historian of Alberta’s early immigration. Rowe noted that ethnic groups of immigrants settled in different patches of Alberta, which shaped the soil and farming practices. Americans were the most common immigrants in southern Alberta and they brought their dryland techniques with them. Central and northern Alberta were settled by a mix of Europeans and farmers from Ontario. Both groups sought a balance between subsistence farming and other tasks including the cutting of wood for sale as fuel and building material. For this reason, groups of immigrants were attracted to trees on the parkland, despite those fields being less fertile than the open prairie.

Rowe explained that experienced farmers brought soil practices with them while new farmers relied more heavily on their kin, agricultural societies, newspapers and mobile government education programs to learn what worked and what didn’t. Alberta’s modern soils still preserve the legacy of early farming brought from Ukraine, Britain, Scotland, Scandinavia, Eastern Canada and the United States and we are still shaping our soils. Soil conservation in the 1980s led to the adoption of zero tillage and other practices that maintain fertility and maximize yield and these practices will be visible in our soils 100 years from now.

Below the furrows of each field is a layered library of landscape change. Anderson said reading these soils reveals an elegant history. Sentiment aside, there is practical value in appreciating soil science and the history of soil formation.

The footprints of early farming and modern land use will be dealt with for generations. “Every time we touch a landscape, we disturb it or take it apart,” said Leskiw. “We need to know how to put it back.”

Comments