MODEL MATERIAL

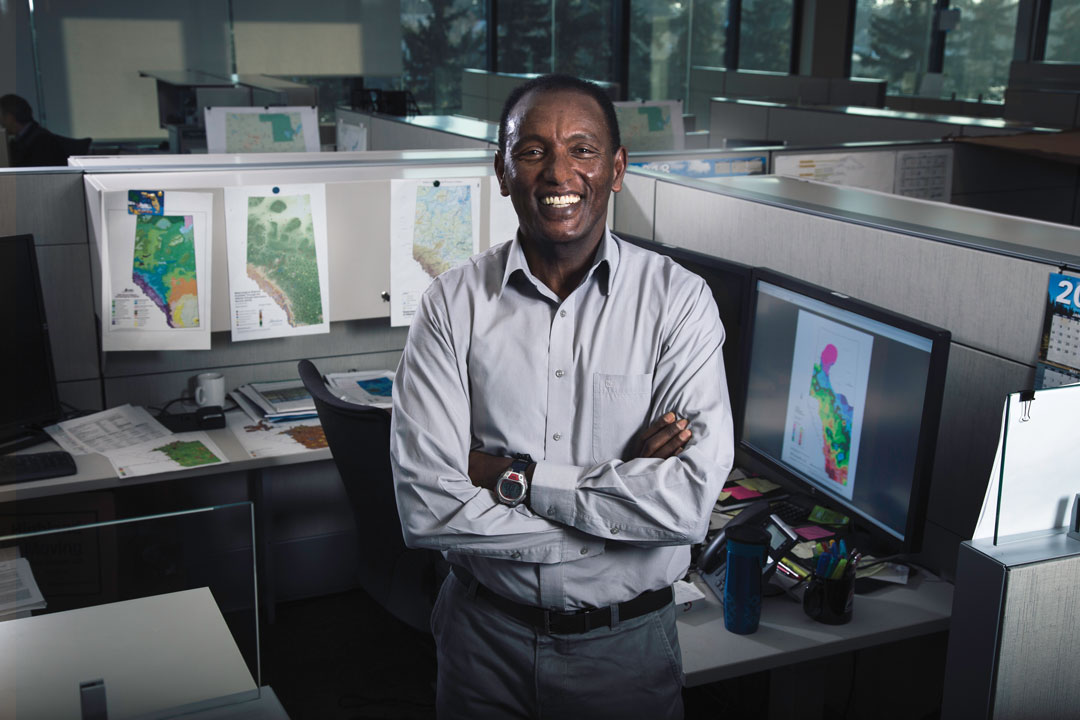

DROUGHT MODELLER DANIEL ITENFISU HELPS FARMERS MANAGE CLIMATE RISK

BY ELLEN COTTEE

No industry is more aware of the value of water than farming. In Alberta, varying levels of precipitation year to year can alternately produce fields of mud and punishing drought. Daniel Itenfisu, a drought modeller with Alberta Agriculture and Forestry’s (AF) AgMet unit, collects data on weather and soil conditions from around the province, which is used to create drought reports and maps that aid farmers. With his international experience, Itenfisu has helped expand Alberta’s weather station network to world-class levels while also helping farmers prepare for emerging weather issues.

GrainsWest: How did you become interested in water management?

Daniel Itenfisu: I am from Ethiopia, and while Ethiopia has quite a few rivers, it is well-known for having problems with drought. I thought I’d better understand water as a natural resource and the science of it in order to solve the problem of drought. I have an agricultural engineering background and did my graduate studies and research in Belgium, in the Netherlands and at Utah State University.

GW: Your passion for drought management has taken you all over the world. What brought you to Alberta?

DI: I was working at Oklahoma State University, with Oklahoma Mesonet, the best weather station network in the world. I often visited my extended family in Alberta and loved the prairie and the mountains. There was an opportunity to expand the provincial drought modelling and risk management program following the drought of 2001/02. So, in 2004, I decided to work for AF, and since 2005, I have worked with what is now the AgMet unit on drought monitoring and reporting.

GW: So, the idea for a risk management program came out of the 2001/02 drought?

DI: That was a critical point. Of course, drought had happened before, but this was when AF and the province decided it was time to track and manage that risk. The traditional way of managing drought was not economical or timely. The province implemented the Alberta Drought Risk Management Plan, using science-based drought reporting to manage the risk. However, when the program was launched, there wasn’t enough weather data to write a scientifically sound drought report.

GW: Why wasn’t there enough data?

DI: The weather data for the agricultural area of the province was primarily based in cities, which meant it wasn’t sufficient in quality and quantity to build an agricultural drought risk management program.

GW: How was the data improved?

DI: AF established a standard drought weather station network consisting of weather stations in the dry land (37) and irrigated areas (10) in the south. You can have a simple weather station on a stick, which many guys have, but they don’t last. Weather stations must be placed right, and you should be able to perform quality control on the weather data. In our standard weather stations, we measure precipitation, temperature, humidity and wind speed at two and 10 metres. Additionally, we measure solar radiation, and profile soil moisture and temperature at selected weather stations. We monitor weather variables every five seconds. We then do quality control to replace faulty data, and report hourly and daily summaries. This is near-real-time reporting.

GW: Do these standard weather stations provide foolproof data?

DI: Sometimes the sensors can fail or report faulty readings, so the computer system uses a quality-control program to identify errors and replace faulty data. We audit each error correction.

GW: How is that data used in the modelling?

DI: The drought risk management and weather analysis is the first part. We need to know where it is dry, what is the extent of the drought, its severity. It’s not enough that we measure—we also need to know historically where it stands. I can’t just report that recently the temperature was cold; it doesn’t make sense until you compare it historically. We went through the historical weather data going back through the last 100 years and we put together a good weather data set that was collected by Environment Canada and others, we organized it, and now anytime we have data, we can compare it going back to 1961. We are unique in that.

GW: What else separates Alberta’s weather analysis from that of other Canadian and North American regions?

DI: From my work experience, Alberta has one of the biggest standard weather station networks. From the 47 stations we started with, we now have 174 weather stations across Alberta. This is thanks to work with other groups including crop insurers. When I started working on this, crop insurers sold plans based in part on precipitation, so they either had to find a network to use or put in the time and money to build their new networks. We convinced them the best option was to expand the existing drought-station network to have reliable data, and we would take responsibility for the data. That started in 2007, and in that first year we added 67 weather stations. That is impressive.

We also make use of all other provincial near-real-time weather station data, do quality control on their data and report it to the public.

GW: How available is the weather and drought data to the average person?

DI: This information is freely available online at the Alberta Climate Information Service (ACIS) website—for updates from our stations to province-wide weather conditions. We also regularly report and map provincial drought and moisture conditions year round, including weather analysis, and publish it on ACIS. Our regular map summarizes the past seven and 15 days, plus monthly, growing-season and cold-season conditions. As part of the provincial crop report, we provide growing-season moisture condition updates every week so farmers know how conditions are. Our models and risk assessment tools are publicly available on our website (weatherdata.ca).

GW: Are there other applications for this data besides drought monitoring?

DI: There is another agricultural risk program I’m a part of. We are developing models that predict insect pest risks across the province. The objective is to provide insect risk forewarning and decision-making support for effective pest management. In 2013, we implemented a daily grassfire danger forecasting model that produces two maps showing fire potential and fire-spread conditions for the agricultural area of the province.

GW: What ambitions do you have for the program?

DI: I would like to continue expanding our weather data use and modelling experience to serve provincial, agricultural and environmental risk management programs. I also would like to expand the success of our weather monitoring network and use of the data to support agricultural and environmental risk management tools in other provinces and around the world, including Ethiopia and East Africa. We’ve been lucky to get the funding we have, and it would be nice to share the experience we’ve had.

Comments