PASS THE SALT

STUDY FINDS BARLEY THRIVES IN SALINE SOILS

BY MELANIE EPP

A study conducted by a team of researchers from King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) in Saudi Arabia has identified a genetic anomaly in barley that allows the crop to grow in high-saline soils. Under saline conditions, 30 per cent more barley plants were produced with the genetic mutation in comparison to a common mother line.

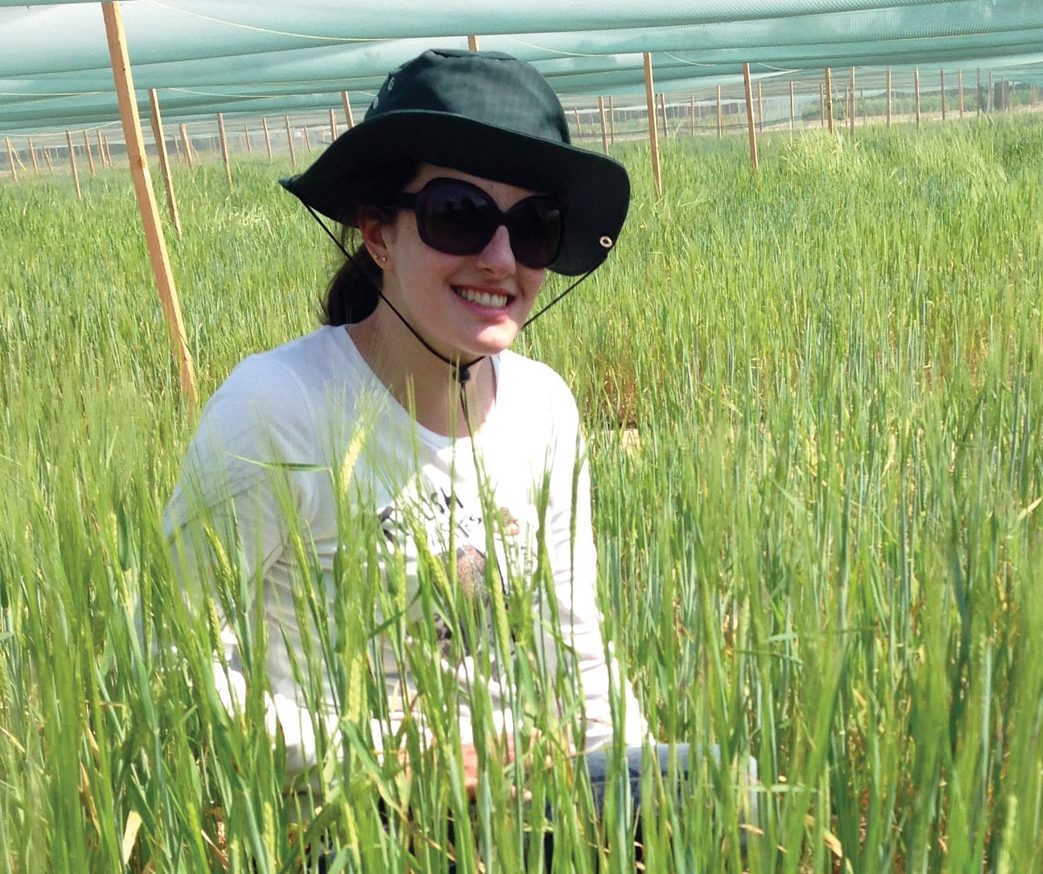

Salinity is an important issue, said KAUST plant science professor Mark Tester—especially since one-third of the world’s food is produced under irrigation and salinity issues affect a quarter of that land. Tester, whose crop of focus is barley, conducts research out of KAUST with the help of his PhD student, Stephanie Saade.

“Why barley? Because it’s salt tolerant,” said Tester. “I can learn tricks from barley that are missing from rice and wheat, both of which are affected by salinity.

“I have a dream of being able to ultimately use seawater or really salty groundwater for agriculture,” he explained.

While Tester doesn’t believe that straight seawater is a viable solution, he does think that partially desalinized water could be used in some crops. His research shows that it is possible in certain barley varieties.

The mother line used in the study, Barke, represents around 75 per cent of the genome of each plant. The researchers used 25 different father lines of wild barley that were shown to exhibit higher salt tolerance in comparison to commercial strains. The team then assessed each for 10 specific crop traits related to crop performance, such as flowering time. More specifically, though, they looked for plant genes that were successful in highly saline soils.

In Tester’s field trials, plants were grown in deep, sandy soil that was irrigated with both fresh and brackish water that was roughly 50 per cent seawater. Plants were later assessed for important traits, such as yield, height, number of heads and grain weight. Intriguingly, researchers found that one father line yielded 30 per cent more than the Barke line. That father line was from northwest Iraq.

Next, said Tester, the goal is to replicate the results. “There’s still a way to go,” he said. “It’s a good start, but now we have to validate it in different backgrounds and different environments.”

The outcome, if it’s validated, could lead to a significant jump in barley yields around the world. More importantly, though, it could pave the way for new salinity research in other important crops, like rice and wheat.

“Having a 10 or 20 per cent jump in yield in barley is good,” said Tester. “But if you could then learn from that and replicate that in wheat… Can you imagine? That would be brilliant.”

Comments