NEIGHBOURS IN NEED

AWARENESS OF MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES IN FARMING COMMUNITIES IS ON THE RISE, BUT FINDING HELP IS NOT ALWAYS EASY

BY ALEXIS KIENLEN

Depression. Mental illness. People in rural communities used to be quiet about these conditions, and many still are. But there’s a growing movement of people who want to talk about depression—who realize how mental illness is affecting people in rural communities.

Gerry Friesen is one of those people. Friesen used to be a hog farmer in Wawanesa, MB, but quit farming in 2007. Now based in La Salle, MB, he works as a consultant and conflict resolution specialist, and often works with farmers. Friesen frequently speaks about mental health issues and his own struggle with depression.

“Back when I was farming, there were certain challenges, and I found myself at one point slipping into a depression,” he said. “It’s been a journey for me and it continues today. I recognize now that it probably started long before I recognized what it was.”

Friesen thought that his problems would end when he quit farming, because his farm caused him significant financial stress.

“I’ve learned since then that that was not the cure-all, although getting rid of a large stressor did help,” he said. “But I still have to be very much aware of what is going on in my life and recognize when I’m slipping backwards again.”

Financial issues are only one of many stressors farmers face on a daily basis. They work long hours and have extremely busy seasons. They face uncertainty because of volatile markets and unexpected weather events. Some farmers struggle with financial management and communication with their families. Shrinking rural communities and fewer neighbours can mean that farmers have fewer people to talk to and resources to access.

Friesen’s story is not uncommon. Many farmers are dealing with mental health challenges. In fact, mental health problems in rural areas may be more prevalent than previously thought.

The University of Guelph recently conducted an anonymous survey to determine the frequency of mental health issues among producers in Canada. More than half of the 1,100 respondents self-diagnosed themselves as experiencing “high stress.”

“Stresses that producers face are continuous and from multiple different sources. Very few of these stresses are under their control,” said Andria Jones-Bitton, an associate professor in the department of population medicine at the University of Guelph and one of the researchers behind the survey. “They’re dealing with changing weather, government regulations, disease outbreaks, herd productivity and constantly changing prices. They work in social isolation, so that’s a factor as well. They work long and hard hours, and rarely does a producer get to leave work. They’re living their work, day in and day out, 24/7.”

Many producers haven’t taken a vacation in years, she added.

“When you think about the wide array of stresses that producers are facing, it wasn’t too surprising—unfortunate, but not surprising—that there were so many in that high-stress category,” she said.

A high proportion of study respondents reported they have experienced anxiety, depression, emotional exhaustion and cynicism, which are contributors to burnout. “All of these things are helping to show everyone that mental health is something that we need to be paying attention to in Canadian agriculture,” said Jones-Bitton.

The University of Guelph conducted the study on rural mental health because there was so little Canadian information available. The university initially wanted to focus on livestock producers living in Ontario, but soon found that farmers from all sectors of the industry wanted to participate in the study. Researchers are analyzing the preliminary data, and will use it to work directly with producers, government, veterinarians, psychologists, social workers and rural family-health teams to address the issue.

“One of the first things we’d like to do is help develop mental health literacy programs that will teach people about mental health. And that will help to break down some of the stigma that we know exists quite strongly, both in general and especially in agriculture,” Jones-Bitton said.

The next phase will also involve creating a mental health emergency response system.

“When the next agricultural emergency hits—like, say, a big disease outbreak or an extreme weather event or a major disaster—then we can be very quick to respond to producer mental health under those crisis situations,” she said.

There was one bright light in the University of Guelph’s findings: about three-quarters of the people who completed the survey said that seeing a mental health professional could be helpful, and they would seek professional help if they were stressed or worried for a long period of time, said Jones-Bitton. Little by little, the stigma is decreasing and people are starting to get help.

However, there are still challenges hampering help for rural residents, many of whom have few formal or clinical services available to them.

“That doesn’t mean that communities can’t support people with mental illness. In fact, historically, Albertans have been doing it in their communities for years using natural supports, community helpers, clergy and family members. In rural communities where there are gaps in services, family, friends and the community pitch in,” said Dave Grauwiler, executive director of the Canadian Mental Health Association’s (CMHA) Alberta division.

Even with help available in the community, the stigma associated with mental health can still prevent people from accessing that help. For example, said Grauwiler, “maybe your sister-in-law is a nurse at the same hospital where you would get support in an emergency room.”

Family and Community Support Services (FCSS) programs are also available across the province and can be easy for people in rural communities to access.

“We see that FCSS in those communities are doing their best to help people find the help they are looking for, whether that is as a caregiver for someone living with mental illness or as someone who is experiencing mental illness in their community,” said Grauwiler. “There are challenges that exist around receiving the support you need, but the biggest challenge is probably understanding what resource to access at what time.”

Alberta Health Services has a provincewide mental health helpline, and many of the regional hospitals offer support in emergency rooms or primary care networks. The CMHA also maintains a website, www.mymentalhealth.ca, that has an interactive map of Alberta outlining CMHA programs and resources across the province.

Additionally, the CMHA has nine regional offices in Alberta and can help people connect with the mental health resources in their area.

“There are still huge areas of the province and communities that are too far away from our offices to be able to access service. We certainly understand that, and so we have to look at mental health delivery as well as what exists within the local community and then what resources can be accessed electronically. It has to be a mix because we’re never going to have everything we need in every community across Alberta,” said Grauwiler.

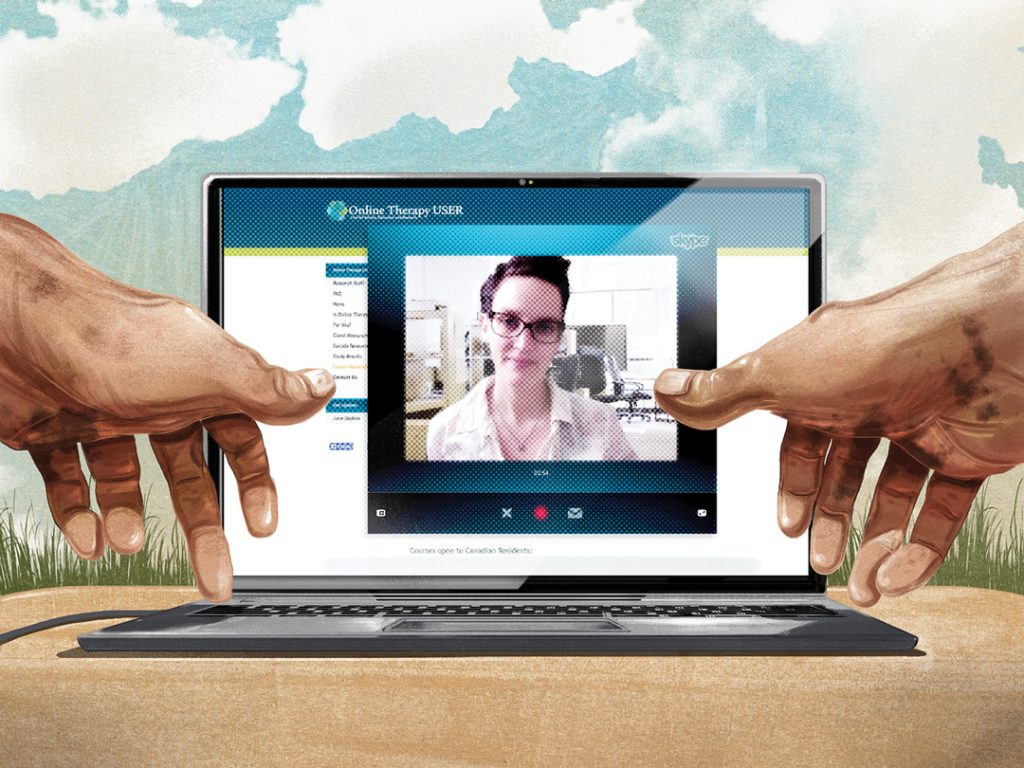

To help more people access support, a team at the University of Regina has developed the first online therapy program in the country, www.onlinetherapyuser.ca. The free program, which offers participants access to a registered therapist, is only open to Saskatchewan residents and serves 400 people a year. Originally designed as a research pilot in 2010, the program is now connected with Saskatchewan’s health regions. Each participant spends eight weeks working through five modules, learning about depression and anxiety, thought-challenging and the physiology of depression. They finish off the course by learning how to reintegrate themselves into their lives if they have been withdrawing, and creating plans that help them stay well.

Marcie Nugent, co-ordinator of the online therapy unit, said the program has worked well with Saskatchewan’s rural residents.

“Access to services isn’t high in the rural areas, although they are covered by the health regions,” she said. “People do have access to psychologists and things like that, but often they do have to travel to get that appointment, because there’s not somebody locally based. Transportation becomes an issue if they’re not able to go into the community as well, and they happen to be in a community where someone doesn’t come out.”

Also, in urban centres, if waitlists are too long for services through the health region, people can choose to pay for services—but this isn’t an option in rural areas.

So far, the reaction to the online therapy program has been overwhelmingly positive. “Ninety-four per cent of clients said that the program is worth their time and they would recommend it,” said Nugent. “Clients seem to think it is valuable, and professionals in the community think that this is something that is needed.”

While the program is the first of its kind in Canada, this type of programming has become popular in the United Kingdom and Australia. There is interest in expanding the program, but no concrete plans to do so yet.

“There are lots of people interested in this in other parts of Canada,” said Nugent. “We have no formalized plans to expand, but we do recognize that it needs to grow.”

One thing that can help people increase awareness of mental health issues and depression is just talking about mental health and being open about mental health issues. It’s also important to know some of the signs of mental health problems.

Friesen said there are four types of mental illness symptoms— mental, social, physical and emotional. Sometimes frequent headaches or a sore back can actually be part of a larger mental health issue. People with depression might also feel tired, have lower energy levels and feel irritable or sad. They might have problems with eating or sleeping enough, or find themselves eating or sleeping too much. Many people who are feeling depressed will withdraw and stop taking part in social events. They might find themselves snapping at the people around them.

Just talking with someone can make somebody with mental health problems feel better, and this can also help to reduce the stigma surrounding mental health.

“From personal experience, I remember a neighbour came by and he just looked at me and said, ‘How are you doing?’ Of course, my response would have normally been, ‘I’m okay,’ or ‘I’m good.’ For some reason, that day I talked and he listened. He didn’t give me any advice. He was a neighbour, another farmer, and so he just listened and normalized and validated what I was feeling. When people can verbalize what is going on in their brains, that in itself is a huge relief,” said Friesen.

He still needs to watch certain things to make sure his mental health issues are kept in check. He watches his nutrition and makes sure to eat properly.

“Make sure that, even in busy times, you take the time to eat,” he said. Getting enough sleep also helps him to maintain his mental health, and exercise makes a big difference as well. “It releases endorphins in your brain, and I know from personal experience that that really helps,” he said.

Friesen said that no one, especially men, should be scared to go see a medical doctor, psychiatrist or psychologist, or to talk about what they’re going through.

“Men in particular, we have this ability to put on this façade. We go out in public and pretend everything is okay,” he said. “It’s better to talk about these things. People feel relief when they learn there are people going through the same things they are.”

Comments