IRRIGATION INNOVATION

CEREALS PROJECTS A DRIP IN THE RIGHT DIRECTION

BY TAMARA LEIGH • PHOTO BY ROB OLSON

When it comes to gambling with nature, irrigation may be a Prairie farmer’s ace in the hole. While competition for water resources between users is increasing, innovation in irrigation technology is providing new tools to help farmers stack the deck in their favour.

In Alberta, roughly 1.7 million acres of cultivated land is irrigated, with nearly a third planted to cereal crops. Overall, irrigated agriculture represents less than five per cent of total acreage in crops and livestock but generates 19 per cent of agricultural sales. Efficiency is the name of the game.

“One of the most interesting things in irrigation is the increases in conservation efficiency; and the gains realized by that,” said Margo Jarvis Redelback, executive director of the Alberta Irrigation Projects Association (AIPA), which represents Alberta’s 13 irrigation districts. “Between 2005 and 2015, the irrigation sector increased its conservation efficiency and productivity (CEP) score by about 48 per cent due largely to efficiency gains. That’s what will drive expansion in the districts,” she added. CEP plans are part of the Alberta government’s Water for Life strategy. The 10-year action plan sets out planning processes for water-using sectors, including irrigation. Most efficiency gains in irrigation have resulted from rehabilitation projects undertaken by the districts, including lining canals to curtail seepage and converting others to pipelines to reduce evaporation.

On-farm irrigation conversions have also created efficiencies, she said. Gradually replacing high-pressure wheel-line and sprinkler equipment, low-pressure, drop-tube pivot-irrigation systems release water close to the crop surface, reducing evaporation and wind drift.

Jarvis Redelback estimates these can take the industry to 80 per cent efficiency, but there’s room for improvement. Farmers are looking to additional technologies to maximize efficiency, including drip irrigation systems.

At its simplest, drip irrigation incorporates the precision application of water using lines and emitters that deliver directly to the soil. The system requires supply lines and a pressure station that runs water to drip lines that are either buried in the field (sub-surface drip irrigation) or laid over the field (surface drip irrigation) to deliver water to the crop. Unlike pivot systems that are limited to a circular watering pattern, drip irrigation systems allow complete field coverage.

IRRIGATING BELOW THE SURFACE

Lethbridge area farmer Ken Coles has partnered with Southern Irrigation—a drip-irrigation products and servicing company—to set up the largest sub-surface drip irrigation demonstration site in Alberta. In 2016, the company installed the system on Coles’ first field, a 110-acre irregularly shaped piece of land now planted with seed alfalfa.

“The goal is to make it easy,” said Coles, who is general manager of Farming Smarter. With a young family and an off-farm career, Coles needed a less hands-on system. Its setup required a substantial field renovation. Permanent water supply lines, or header lines, were installed. These run water to drip lines trenched into the field to provide water from below. Drip lines, also called drip tape, are similar to hoses and feature water emitters at specific intervals. In Coles’ fields, the drip tape is buried 25 to 30 centimetres and 100 cm apart with emitters every 46 cm. A pump that maintains consistent water pressure and liquid fertilizer tanks feed into the system in a process known as fertigation. Field moisture sensors and a controller allow Coles to operate the setup from his home. “It’s like an underground sprinkler system with automatic controls set up in your house. I program it to turn on when I want it to,” explained Coles.

In 2016, his drip irrigation project yielded 76 bushels per acre of canola, and he estimated he would have gotten just 45 to 50 with wheel lines. The result was so promising he installed another 18 acres the second year.

The learning curve and cost of equipment and installation are potential barriers to drip irrigation, but for Coles, the benefits outweigh these factors. “With irregular-shaped fields, I was going to have to buy a quarter-section pivot, and only get 80 acres irrigated. That drove the decision,” he said. “You can put the drip tape everywhere. My coverage is always perfect. Windy or not, there’s no evaporation.” Benefits also include reducing disease risk by not wetting the canopy and maintaining irrigation while crops are flowering and pollinators are active.

“It’s not just one change you make, it’s two or three in the system,” said Coles. I moved to a precision planter, and I precisely put that over the lines. I have precision fertilizer through the drip system in conjunction with zero tillage—three sets of changes that together might make a big difference.”

WEIGHING THE BENEFITS

Irrigation isn’t common in Peace Country, but recent droughts and the prediction of diminished future precipitation have farmers consider investing in systems. In 2016, the Mackenzie Applied Research Association (MARA) started surface drip irrigation trials, making it an irrigation innovator.

With financial support from the Alberta Wheat Commission, MARA field trials are assessing the effects of drip irrigation and fertigation on wheat. Because moist crop environments favour fungi growth, fungicide use is incorporated in the trials.

“Before the irrigation project, we had only one producer in the county who had a permit for irrigation. We’ve helped seven design systems and apply to the Alberta government for irrigation permits,” said Jacob Marfo, manager of MARA.

Results are promising, showing increased yield when irrigation and nitrogen application are combined, and that it’s a significant factor in increasing bushel weight and 1,000 kernel weight. While trial data is still being collected and analyzed, Marfo believes seeing the equipment in action helps area farmers assess their options.

“We have one producer here with huge pivot irrigation looking at how he can either make that very efficient or change the whole system to drip,” he said. “People with old pivots are making modifications—changing the guns and nozzles or putting lines on the irrigation heads so wind doesn’t affect them.”

Willemijn Appels is the Mueller applied research chair in Irrigation Science at Lethbridge College. Her program works with farmers and irrigation companies to evaluate new irrigation tools and techniques, including soil moisture sensors, drones, weather stations, variable-rate and drip irrigation.

“It’s sometimes difficult to figure out what’s valuable and what isn’t. Think about the tools you need to use your new technology to its potential,” said Appels.

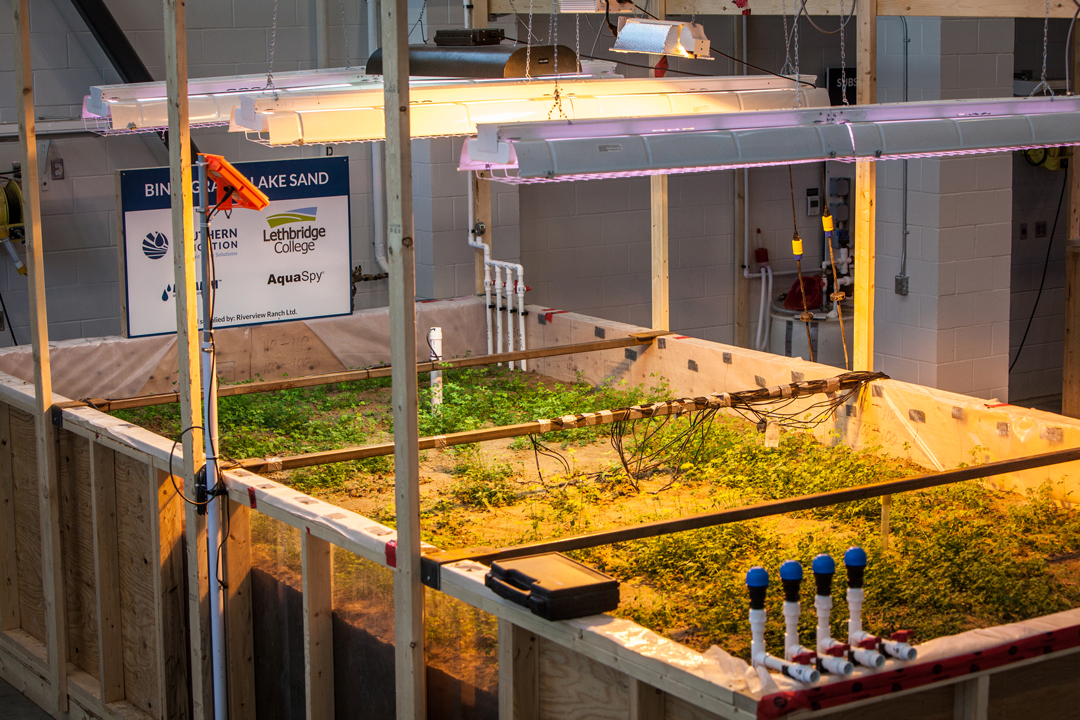

Appels is now conducting indoor, sub-surface drip irrigation trials year-round. Soil and irrigation equipment are contained within three wooden boxes sided with a transparent Lexan panel, allowing moisture penetration of the root zone to be viewed. With soil instrumentation, Appels follows moisture movement. More than a mere outreach project, it will produce management recommendations for Alberta crops and soils.

In predicting the potential for increased Alberta cereal crop irrigation, Appels is pragmatic. “A lot of grains will also grow and produce yields without irrigation, but you will get a higher yield if you add extra water.” Similarly, while drip irrigation may offer a viable alternative to conventional systems and offers opportunities for fertigation, Appels is hesitant to dub it the go-to irrigation setup for grain growers.

“A quarter section put into sub-surface drip irrigation is not going to be economical,” she said. “For a weird corner or an oddly shaped piece of land where you need to make substantial changes to a pivot or conventional irrigation system, it could work, but it will depend on local factors.”

Comments