POWER SURGE

BY IAN DOIG • ABOVE PHOTO COURTESY OF GROWTEC

In an enclosed handling facility at Nature Energy Månsson, a biogas plant in Brande, Denmark, a massive claw hoisted a mixture of manure and straw. The facility works co-operatively with 50 livestock farmers who supply manure for off-gassing. This carefully contained, excremental mess stands in sharp contrast to the plant’s gleaming exterior.

In June 2022, GrainsWest toured the facility, which was launched in 2017. It is obliged to use 75 per cent manure and other agricultural waste. Mette Hansen, a mechanical engineer and the facility’s corporate director, explained the value of being a good neighbour, given its malodorous feedstock. The plant keeps odour in check and the facility’s exterior and manure-hauling trucks are spotless. While staff work hard to impress the locals, the world has taken note of the Danish biogas system.

Denmark is blessed with a rich supply of livestock manure. This allows its many biogas plants to collect fresh manure for off-gassing at peak ripeness. “We borrow from the farmer, and they get it back,” said Hansen. The individual farm’s contribution is mixed with various manure types such as cattle and pig plus additional biomass, usually food waste. With the aid of anaerobic bacteria, the Nature Energy digester collects methane from this mixture to produce renewable natural gas (RNG). The farmer receives digestate, the bioproduct of the process a high-nutrient crop amendment similar to liquid manure that can reduce the use of synthetic fertilizer. Food-quality “green” CO2 is also produced. While the methane is used as an energy source rather than being released into the atmosphere, the farmer receives a cut of whatever profit is derived.

Europe’s biggest biogas producer, Denmark has aggressively funded its biogas economy. While it has predominantly generated electricity, as of 2020, the country produced 475 million cubic metres of RNG annually. Canadian biogas production has developed in a slower, piecemeal fashion, but has taken cues from the Danes.

A 2020 survey by the Canadian Biogas Association identified 279 biogas projects across the country, said Jennifer Green, the organization’s executive director. This includes 61 anaerobic digesters as well as wastewater facilities and landfill gas capture. “That number is relatively small compared to some other countries, particularly the U.S., which has been accelerating incredibly, especially within the ag sector,” said Green. “We have untapped potential in feedstock opportunity in Canada.”

There is opportunity for farmers to join this circular process as suppliers or to construct their own facilities. “By layering biogas and RNG into their business model, it’s a natural next step,” said Green. She cautions biogas operations are not for everyone, given the complexity of the systems involved and the steep learning curve. “It is a living, breathing animal. All the tools the farmer brings to the table with their electrical, mechanical and biological education are integrated in these systems.”

BIOGAS PIONEERS

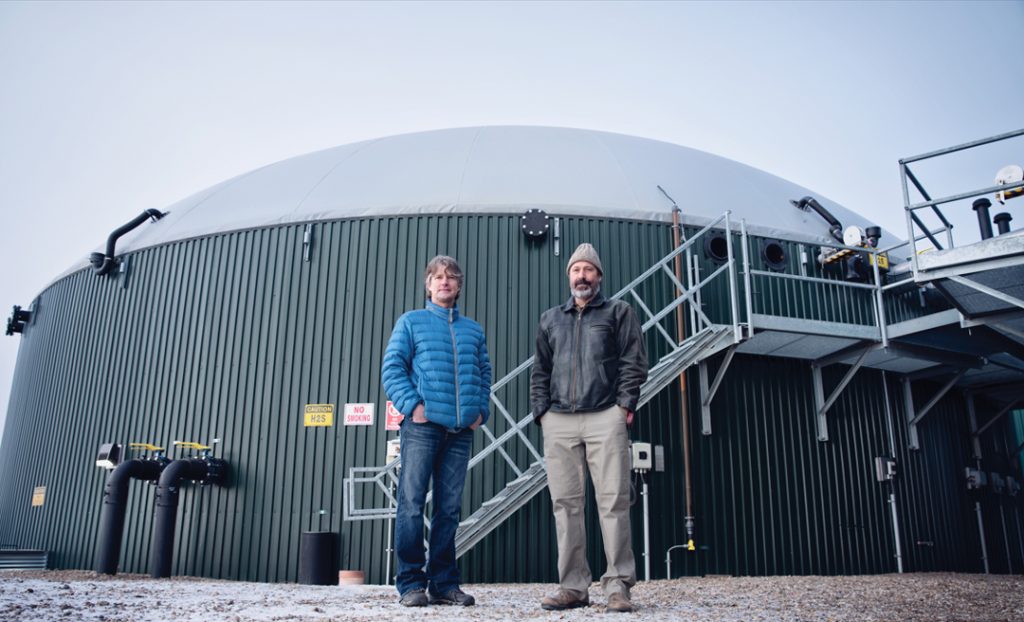

The Perry family grows grain, potatoes and other vegetables on their 5,000-acre farm near the village of Chin. Chris, Harold and their father Gerry built an on-farm biodigester in 2014 that relied upon the farm’s own culled potatoes as its main feedstock. While his father and brother now handle agronomics, Chris is founder of GrowTEC, the family’s biodigestion business. It remains one of just a few in the province. “In Alberta, in Canada, biogas has a great role to play in energy infrastructure,” said Perry.

Interest in Canadian biogas production has recently picked up, too. The Royal Bank of Canada, BCG Centre for Canada’s Future and the Arrell Food Institute prepared a report on sustainable food production for the 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference in November of 2022. It calls for government to support the ag sector in the implementation of new technology with the development of infrastructure, systems and national verification standards. Among these technologies is biogas production.

Until now, the Perry biogas plant produced methane used to produce electricity and to heat farm buildings. Over the years, the scope of the project expanded as the facility accepted a mix of farm and food waste from the surrounding area.

The Natural Resources Conservation Board mandates farm-based digesters use a minimum of 50 per cent livestock manure as feedstock. GrowTEC typically uses 60 to 70 per cent manure by weight as well as potatoes, food processor waste and grain screenings. The process guarantees weed seeds are rendered non-viable. The same goes for grain contaminated with ergot and other diseases.

In July of 2022, EverGen Infrastructure purchased a 67 per cent stake in GrowTEC. EverGen is an RNG developer that owns and operates four Canadian facilities from B.C. to Ontario. The partners are now upgrading the GrowTEC plant to produce RNG. Whereas biogas is composed of 60 per cent methane on average, RNG contains 99 per cent. This will be fed into the FortisBC pipeline network as part of a 20-year offtake agreement. An energy utility company, FortisBC will convert 15 per cent of its gas supply at minimum to such carbon neutral sources by 2030. When GrowTEC’s two planned expansions are complete, the project will supply 140,000 gigajoules of RNG annually. This contains enough energy to equal the yearly electrical needs of approximately 2,800 homes. And this is just one single digester on one farm.

Perry was convinced to market energy beyond the farm while attending a Canadian Biogas Association conference a couple of years ago. There, an official from the Ministry of Environment and Food of Denmark spoke about that country’s biogas industry, which forms a hub-and-spoke business structure with biogas facilities supplied by regional farm and agri-food operations. The approach rang true for Perry, and the EverGen partnership proved the means to implement it. Though the plant initially produced electricity, the biogas market evolved to favour RNG production. “We just never saw the support mechanism come in the electricity market that was coming down the pipe in the renewable natural gas market,” said Perry. The initiative also mitigated some risk for the family who can now provide input on the agricultural side of the business while EverGen handles day-to-day gas production.

Industry growth is now driven by increased focus on getting renewable energy in the gas grid, said Chase Edgelow, EverGen CEO. “The biogas potential of agricultural and food waste has been overlooked in Canada. What’s changed the dynamic is demand from consumers for more green energy.” Whereas the electrical grid has a large renewable component, this is not yet so for the gas market. “We’re just starting to see the increased focus result in more and more RNG projects in Canada.”

The sector has moved in the Danish direction. “Biogas needs to be a distributed model; a lot of smaller players are much better than one big one,” said Perry. GrowTEC handles relationships with local feedstock suppliers and creates a unique contract with each manure supplier, some of which may take digestate. Much of the GrowTEC digestate is applied to the Perry family’s own land.

EverGen provides infrastructure access and manages the relationship with FortisBC. As Canadian biogas production has grown, the feedstock market has become more competitive, said Perry. “Because EverGen has four facilities now and hopes to grow, they can create relationships with bigger waste haulers and bigger agricultural producers across the country that will hopefully add value those facilities.

“The biggest challenge with the waste is there is lots of availability but there is a contamination problem,” he added. Much potential feedstock contains plastic, dirt, rocks and other materials. Similarly, curbside organic material contains much plastic. Such “dirty” feedstock requires pre-processing to be useable. The problem must be solved, but progress is slow, said Perry.

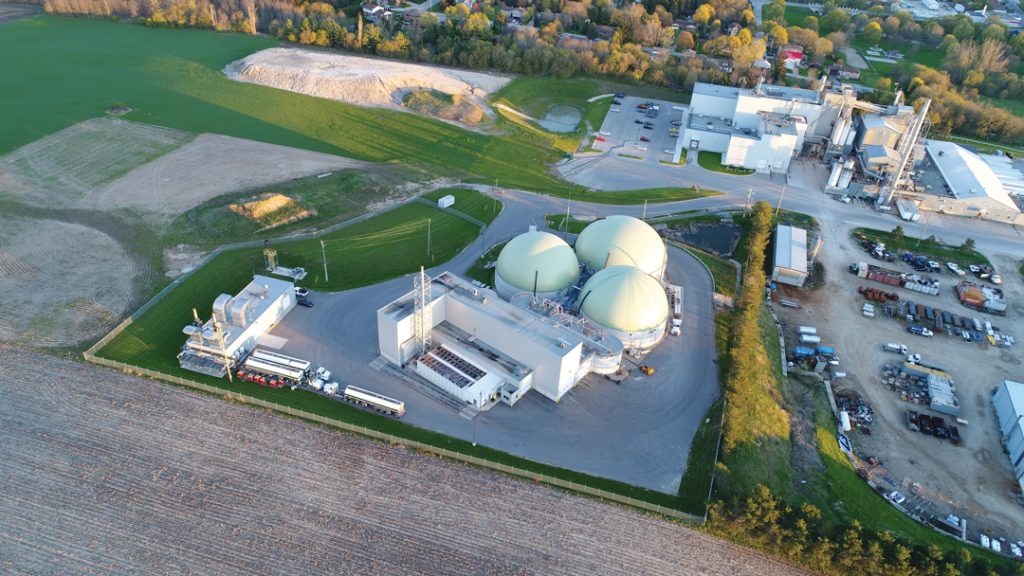

Skyline Clean Energy partners with Bio-En Services and Technology, which designs, owns and operates biogas facilities. These include a biogas plant in Elmira, ON, and Lethbridge Biogas, which the partnership purchased in June 2022. They also aim to construct a new Alberta facility to process municipal organics, said Deanna Martin. Bio-En director of operations, she ran the Elmira plant, her family’s business, for a decade. Like the Perrys in ag biogas, they were pioneers in processing urban organic waste.

Despite its relatively low energy content, said Martin, agricultural projects have great appeal where manure is plentiful. The addition of sources such as urban food waste boosts gas yield and economic viability. Lethbridge Biogas had made its money on a combination of tip fees paid by feedstock contributors and electricity production. Just over a year ago, its new owners also launched their own 20-year RNG supply agreement with FortisBC. “The [electricity] pool pricing is quite volatile,” said Martin. “It’s really difficult to do any sort of financial modelling or forecasting. That RNG contract really brought a degree of stability to the operation.” Though the plant now exchanges digestate for manure for free, this model may also evolve. “There’s quite a decent N-P-K value in this stuff,” said Martin. “We’re trying to figure out what the market will bear.”

The mix of locally available feedstock determines the size and design of a given biogas facility. “We’re technology agnostic,” said Martin. “We design these facilities on an individual basis.” For example, if the main contributor is a feedlot with dirt pads, a process for grit removal may be necessary. “Design choices like that have a big impact on the long-term viability,” she said.

Bio-En has developed a process it has dubbed “smarter organics management,” to separate difficult-to-remove plastic and other materials from feedstock. This allows it to access rich biogas sources that would otherwise be unusable and ramp up the use of new feedstock quickly. “There is not really a waste stream we’re scared of,” said Martin.

Martin emphasized biogas plants produce truly green energy and the methane they capture is a very potent greenhouse gas. Their inherent sustainability has driven the rise of the sector. “Climate change is almost indisputably real, because insurance companies are starting to charge for it. They’ve seen a pinch on their bottom line and pass that cost down primarily to industry. Economic pressure to do better with carbon is going to strengthen our position within the marketplace.”

SUPPORT SYSTEMS

Targeted support has been critical to the biogas sector, but a patchwork of programs varies between provinces, said Canadian Biogas Association’s Green. “And that’s one of the challenges. How does one wade through to figure out which pathway to take?”

Perry admitted being ahead of the curve has been economically challenging. His family’s facility would not exist without an initial 50 per cent capital grant from the Climate Change and Emissions Management Fund, which is now Emissions Reduction Alberta. The bio-producer program introduced by the Notley government further contributed to its viability. In going the RNG route, 20 per cent of capital cost of the GrowTEC overhaul is connection to the grid. Perry believes such costs have limited biogas investment, but he envisions biogas plants as building blocks for economic opportunity. “They’re like distributed energy packs spread across the landscape.”

The biogas sector has yet to receive sustained government support in Alberta. Programs tend to be one-offs. Without ongoing subsidies, high-value feedstocks are being lost to the U.S. where the return is more substantive, said Perry. Edgelow suggested Ontario has led the way in the creation of a streamlined regulatory process other provinces can emulate to encourage development. Incentives may also include funds for construction of biogas facilities and infrastructure projects such as feedlot renovations that support the collection of manure, he added.

Various resources are available for prospective biogas entrepreneurs. While the Canadian Biogas Association advocates for the industry and calls on government to support stable RNG markets to foster growth, it also provides information for prospective entrepreneurs at farmingbiogas.ca and will soon publish a digestate management guide. “The growth for biogas in ag in Canada is only going to expand and grow,” said Green. “The future is very bright, but it will not be easy.”

Earl Jenson is director of the bio-industrial services division of InnoTech Alberta. The Alberta Innovates subsidiary offers comprehensive startup assistance, system evaluation and design as well as training courses and manuals. Its pilot scale biogas equipment aids the development of new projects. While the performance of feedstock such as dairy manure is well understood, for new and untried sources, test runs on these systems are highly valuable, said Jenson. For instance, some feedstocks can prove unexpectedly “hot,” and their richness overwhelms the bacteria. Like people, these micro-organisms require a well-rounded diet, said Jenson. Meat-and-potatoes is preferrable to living on chocolate cake.

Like Green, Jenson praises biogas as a methane-emission reducing renewable energy source, but cautions production is complex and capital intensive. Since he joined the industry in 2001, biogas has developed in waves along with incentive programs. The latest are renewable natural gas pricing incentives and carbon offsets—the latter of which, dry manure notably does not fully qualify for. He said economies of scale can be created, but pricing can only go so low. The solar sector benefitted from increased production of ever-improved solar panels that drove costs down, but this is impossible for the pumps and tanks central to biogas production.

FortisBC offers RNG pricing as high as $30 per gigajoule for RNG, he cited. A new project that has a production cost in the mid to high twenties may not prove lucrative as it might in the U.S. where various states have instituted layered carbon incentives. “When you compile them all together—I’ve heard numbers as high as US $70 for RNG—now, that makes a project,” said Jenson.

His guiding principle for biogas entrepreneurs is simple. “Do your homework: understand your feedstock. Let the feedstock define your decision-making processes and dictate techniques and equipment.”

THE TIME IS RIGHT

While industry pioneers such as GrowTEC and Bio-En endured much trial and error, they offer encouragement to newcomers. “If you’re considering a biogas project, think about your inputs,” said Martin. “What else in the area could potentially be an input, what am I going to do with the gas and what am I going to do with the digestate? If you can answer those three questions, you’ve probably got a project on your hands.”

“The time is right,” said Perry. “It was not when we did it. Now, the support mechanisms are there.” He advises interested parties thoroughly investigate environmental permitting, access to energy markets and utility grids and the availability of feedstock. He also suggests they contact industry consultants and successful biogas facility operators for input.

Perry is confident Canada’s biogas sector can come to grips with market complexities. “It’s what Alberta and the West need as a story. It’s going to take a little money, but once it’s going, it will be a sustainable energy industry long-term.”

Comments