THE FUTURE IS NOW

THE OLD GUARD PASSES THE TORCH TO CANADA’S NEXT

GENERATION OF AG RESEARCHERS

BY TAMARA LEIGH

In agriculture, succession planning isn’t just an issue that affects the farm. As senior researchers in government and postsecondary institutions near retirement, the pressure to recruit the best and brightest students into agricultural research is getting higher.

“In tough times, succession planning is usually one of the first things hit because it takes time and training,” said Clair Langlois, cereal extension specialist with Alberta Agriculture and Forestry. “In the long term, it’s not necessarily a wise way of going.”

Langlois has had a long career in applied agriculture research. Now his job is to bridge the gap between producers with questions and the researchers who can provide answers.

“Young researchers come to the industry with fresh ideas, fresh perspectives and new energy,” he said. “We need to have a constant influx of them so we can have our research icons mentor them before they retire.”

Facing complex issues including climate change, herbicide-resistant weeds and productivity challenges, agricultural research is essential when it comes to helping farmers innovate, adapt and remain viable into the future. In some ways, it is the complexity of these challenges, and a desire to make a difference in people’s lives, that make agriculture attractive to the next generation of researchers.

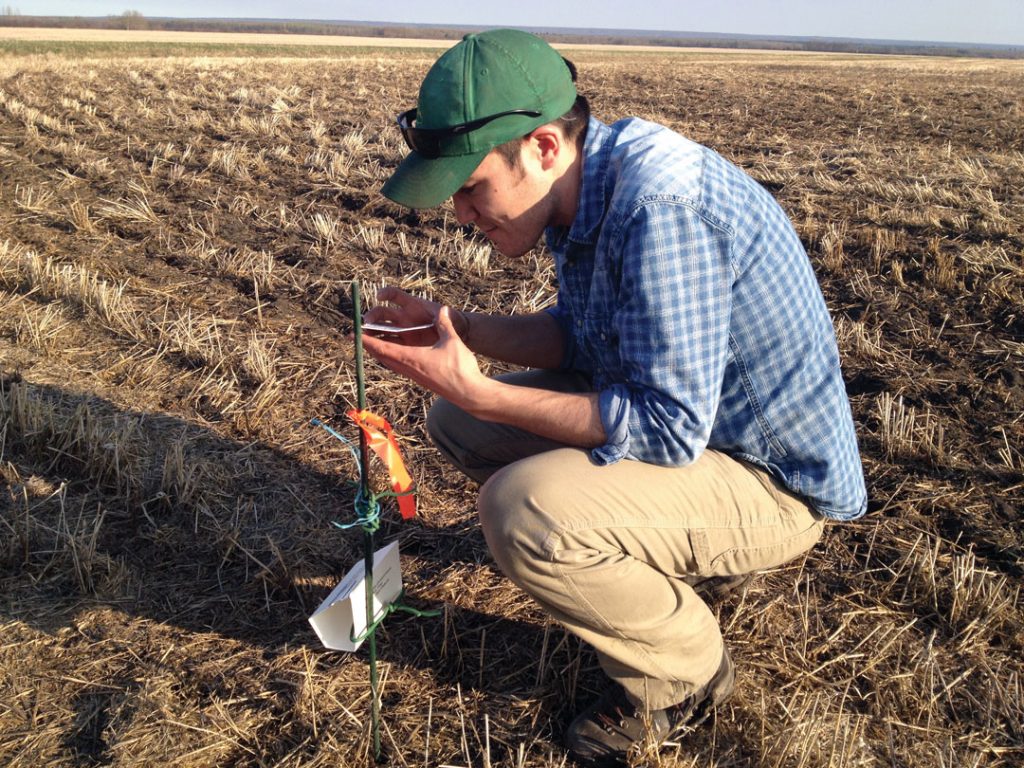

Breanne Tidemann, Laurel Perrott and Boyd Mori are three fresh faces in the field of agriculture research. Their work and their journeys are different, but they share a common goal: to find practical solutions to agriculture’s most pressing problems in order to move Canada’s agriculture sector forward.

BREANNE TIDEMANN

Research scientist, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

Breanne Tidemann likes to know her work is making a difference. She grew up on a grain farm in Saskatchewan, but decided to study biological sciences on her way to becoming an orthodontist. Two years into her studies, she found out she didn’t like teeth, triggering an early-life crisis.

Her interest in agricultural research was sparked when she went home that summer and got a job at Agriculture and Agri- Food Canada’s (AAFC) Scott Research Farm, 10 minutes down the road from her family’s farm.

“I fell absolutely in love with agriculture research. For me, it was an applied way to use my science background,” said Tidemann, adding that she sometimes struggled to see the point of some of the pure science work she did in school.

“Agriculture research was still science—it was still asking the questions and trying to figure things out—but with a direct application where I could see that if we work on this new herbicide, or this new fertilizer rate, this could help my dad on his farm,” she said.

Tidemann completed her undergraduate degree and spent some time working in different areas of agriculture before deciding to pursue a master’s at the University of Alberta in weed science. It proved to be a good fit, and veteran research scientist Neil Harker recruited her to AAFC’s Lacombe Research and Development Centre, where she was offered an opportunity to work full time while she completed her PhD.

“My primary area of interest has been weed science and looking at new ways of managing, in particular, herbicide-resistant weeds. In places like Australia and the U.S., they’ve had a more significant problem with herbicide-resistant weeds than what we have, but we expect our problems to continue increasing as long as we rely solely on herbicides for weed control,” said Tidemann. “In my master’s, I was looking at new herbicide molecules we could use, and then I got into more non-chemical control measures in my PhD.”

As she wraps up her PhD, Tidemann is excited about what the future holds. She has been hired as a research scientist to replace John O’Donovan, who retired last year from AAFC’s Lacombe agronomy program, and she will continue the weed program in Lacombe after Harker retires. She said she is grateful for the opportunity she has had to work on and learn the programs while she completed her PhD, as well as the continuity of the technical staff who support the programs.

Despite the challenges of establishing networks, and trying to secure project funding when you’re starting a career, Tidemann said she has been greeted warmly by the industry.

“People have been very willing to provide information, advice and guidance,” she said. “It can be a bit tough to break into the typical collaborations—you have to be a bit more outgoing than I necessarily expected. You have to be the one to reach out and say ‘I’m here and I’m looking for projects.’”

LAUREL PERROTT

Crop researcher, Lakeland College

Growing up in a rural setting doesn’t necessarily mean you will know a lot about agriculture. That was the case for Laurel Perrott, until she connected with a group of agriculture students while she was working on her undergraduate degree in science at the University of Alberta.

“I knew farming existed and thought it was great, but it never occurred to me that I could do that as a profession,” Perrott said. “I didn’t understand that there was a whole industry behind it.”

The budding researcher transferred into the crop sciences program at the university, then worked for Cargill in Vermilion for a year-and-a-half after graduation before she decided to go back for a master’s degree in barley agronomy.

Since her discovery of agriculture, Perrott has made the most of her time in the field. While she was still working on her master’s research, she accepted a full-time job to start up the crop research program at Lakeland College.

“When I came to Lakeland College, they had just started thinking about doing small-plot research and they had bought a combine, but that was about it,” said Perrott. “We got a first season under our belt last summer. We did a few of our own trials and collaborated with Linda Hall from the U of A on some plant growth regulator work. It launched us off, got us some experience collaborating and got our name out there.”

The program has taken off since Perrott joined the applied research team to expand the crop research program. She has been able to use her relationships and expertise to set up more collaborative projects for the 2017 growing season with Hall at the University of Alberta and Sheri Strydhorst at Alberta Agriculture and Forestry, looking at forage agronomy and cultivar-specific wheat agronomy.

Perrott will defend her master’s thesis this spring, and said she will likely take a break before considering a PhD.

“What excites me about the future with agriculture research is that I know the career is always going to be challenging and changing,” she said. “It’s always striving to discover new and valuable things for farmers that drives me.

“I’ve been living on a mixed farm with my fiancé for the past few years, so I have a foot on the farm and a foot in research. It helps me identify where we should be researching and what challenges farmers are running into.”

As someone who wasn’t raised farming, Perrott said it took time and a concerted effort to learn about the business and the culture of the industry. She sought out learning opportunities and asked her friends if she could help on their farms. Throughout this learning process, she has developed an appreciation for how much there is to know and the importance of communication.

“To farmers, researchers are getting better at working with them and understanding on-farm logistics and what drives the management decisions that might counter what we find in research,” she said. “I think it would be valuable to have a more open dialogue between farmers and researchers. Farmers are smart people—they have a lot of good ideas and recognize production challenges on their farm. If those ideas are shared more, they will turn into research. More cross-communication will benefit everyone.”

BOYD MORI

Entomologist, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

Sometimes it’s the little things that really captivate people. For Boyd Mori, he followed his interest in insects into a career in agricultural research.

Mori grew up in Abbotsford, a mid-sized city in the middle of British Columbia’s berry belt. No one in his family farmed, but like many young people in the area, he picked berries when he was in high school, and even worked on a daffodil farm in the Fraser Valley.

“I had no idea I would end up working in agriculture,” said Mori, who did his first degree in immunology at the University of Alberta. “I took a few courses in entomology and plant science that I really enjoyed, so I went back and did a second B.Sc. in animal sciences with a focus on entomology. The research kind of drew me in.”

Entomology, the study of insects, offers a diverse array of opportunities for study, from horticulture and agriculture to medical and veterinary entomology. After completing an undergraduate honours project on the mountain pine beetle, Boyd decided to pursue a master’s degree.

“My supervisor, Maya Evenden, had an opportunity for a M.Sc. student to start a funded project to work on red clover in the Peace Region. From that point forward it has all been agriculture,” said Mori, who subsequently went on to complete his PhD as well.

Mori is currently an entomologist with AAFC at the Saskatoon Research and Development Centre. His work is primarily focused on the swede midge, a small fly that affects canola and other brassicas.

“Swede midge is devastating in Ontario, and turned up in Saskatchewan in 2008. They noted it was here and they noted some damage symptoms, but it’s not a huge pest like it is in Ontario,” Mori said. “So what’s different in Saskatchewan compared to Ontario?”

Mori is looking at host-plant resistance to determine what plant hosts swede midge can attack, with a particular focus on weeds like wild mustard, stinkweed and peppergrass. He is screening the alternate hosts to determine whether they have swede midge-resistant properties and why.

“If we can figure that out, potentially we can dive deeper into the genetics of it and [find out] if it’s a particular gene that is enhancing resistance. If it is, we could potentially give [that information] to breeders so that they could incorporate that into canola lines or other brassica vegetable lines,” he said. “We are trying to use the plant to combat the insect rather than have to use a secondary approach.”

Mori’s work blurs the line between field entomology and lab entomology. While the fieldwork keeps him grounded, being able to bring new tools to bear on a problem—like genetic investigation—deepens understanding and opens up possibilities for new approaches.

“I think we’re getting more integrative in agricultural research,” he said. “You’re not just an entomologist working on a problem. We’re working with so many different people—plant breeders, geneticists, even engineers. It’s looking at the whole agricultural system. You can’t just focus on one single thing. You really have to look at the whole ag system and see how you can improve it.”

DOES MORE NEED TO BE DONE?

The recent infusion of young talent into agriculture research is a good sign for the industry, as well as a relief to some of the researchers who are nearing the end of their careers.

Harker, one of Tidemann’s mentors, has spent 32 years doing weed research and field research. As a research scientist in weed ecology and crop management at AAFC’s Lacombe Research and Development Centre, he will be looking to researchers like Tidemann to carry on the valuable work he has done for the industry.

“For a few years, we were hard-pressed to find any graduate students in my area of weed science and general agronomy. There were very few that were taught in the western Canadian situation,” said Harker noting that interest is on the rise and there are now a number of qualified students working in the field.

Like any occupation, attracting and retaining talent to agriculture research means there have to be jobs available and funding to support the work. Harker said the federal government is starting to hire researchers again, after years of program cuts and fiscal restraint.

Industry also needs to display leadership on this front. Langlois’ position with Alberta Agriculture and Forestry was created when producer groups identified it as a priority and pushed for action. They are also pushing for research investment and providing the much-needed matching funds to get projects off the ground.

As more and more young people grow up without a direct connection to agriculture, they need to be made aware of the science-based opportunities that agriculture has to offer in areas like computer, satellite and engineering technology, as well as plant and animal sciences.

“One of our challenges is making people aware that agriculture is a very vibrant and forward-looking industry in terms of new technology,” said Harker.

It’s a sentiment that Langlois echoed, while taking it one step further. “We don’t do a very good job of promoting agriculture as a science-based industry like other sectors do,” he said. “We’re not going to promote more Canadian youth to get involved in science and agriculture without promoting agriculture first.”

Comments