KNOW YOUR LIMITS

BY LYNDSEY SMITH

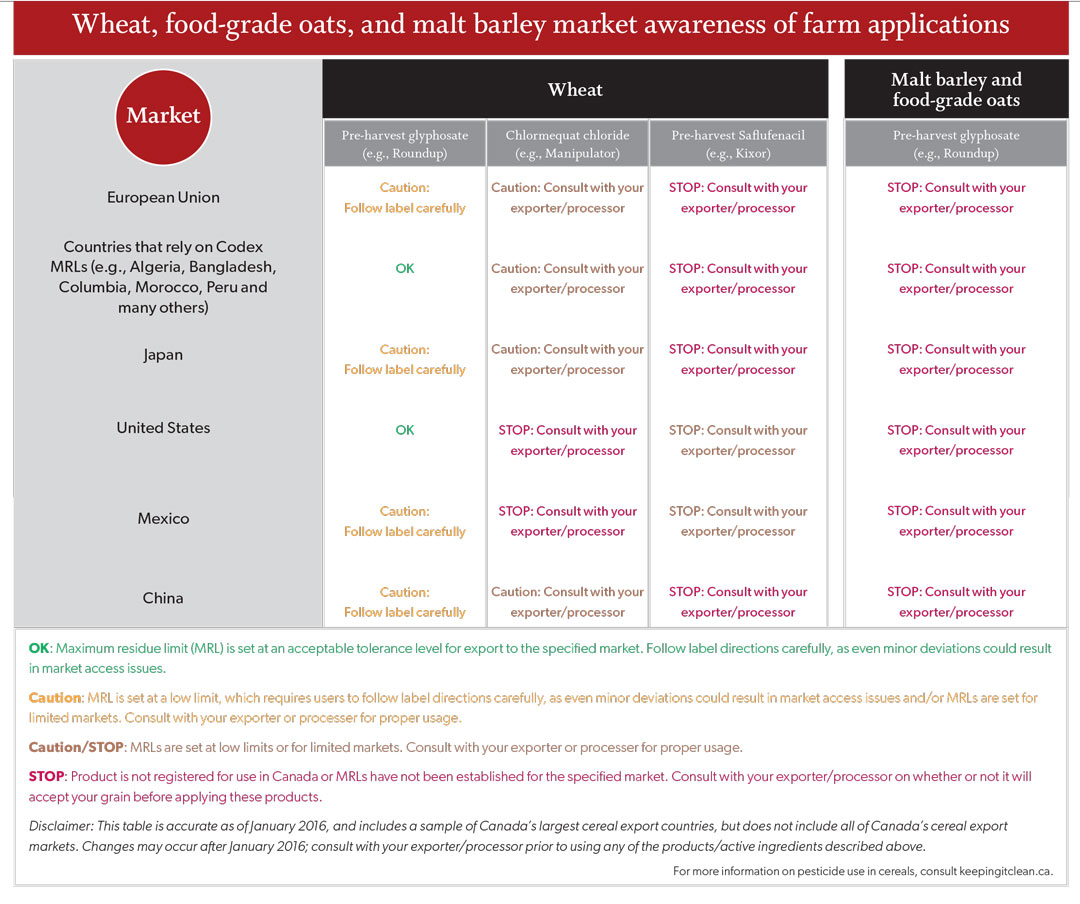

If you don’t know what MRL stands for, you can be forgiven. Maximum residue limits have been, until recently, not something that most grain farmers in Western Canada have had on their radar. If you bought registered crop protection products and used them according to the label, all was well.

That’s not entirely accurate, of course. Whether you knew it or not, establishing and monitoring global MRLs has been an ongoing process since the 1960s. In the absence of a problem, it’s not something many farmers would have had to worry about. In 2011, however, MRL issues following glyphosate use on pulse crops destined for Europe brought the issue to the fore. Then, in 2015, the lack of an MRL in the U.S. for the plant growth regulator Manipulator prompted grain buyers to refuse grain delivery and ask for declarations of use.

Can these trade disruptions be avoided? To a degree, yes, but MRL setting and management is a complex, global issue. It’s important to first understand how the MRL regulatory system works.

HOW MRLs ARE SET

Each and every crop protection product registered in Canada is subject to an MRL—an allowable amount, in parts per million, of residue on the harvested grain or oilseed.

In Canada, once a new crop protection product is created, the crop protection company submits reams of data to the Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA) in support of product registration. The PMRA then not only assesses the product’s crop safety and other parameters, but also its safety to human health. “Health Canada must determine whether the consumption of the maximum amount of residues, that are expected to remain on food products when a pesticide is used according to label directions, will not be a concern to human health,” reads the PMRA website.

Countries around the world can establish their own MRLs through something similar to the PMRA, or by referring to the global MRL database known as Codex Alimentarius, or Codex, with all risk assessment done by the World Health Organization.

Because each country decides on its own way to deal with MRLs (or which products have them), the MRL regulatory layer can cause headaches in the grain trade. In the case of a new product, there’s always a time lag—one or two growing seasons, typically—between a product’s registration in the country it is to be used in and the establishment of a Codex MRL in exporting countries. The second hiccup can occur when a mature product is destined for markets where the MRL is zero or defaults to zero in the absence of a set level.

MISSING AND MISMATCHED MRLs

Some products carry a very low risk of any residues ever being present—think seed treatments—but most products, especially those used later in the season, are likely to leave some tiny residue behind. That’s where an MRL of zero causes problems.

“Here’s the trouble with zero,” said Cam Dahl, president of Cereals Canada. “We can now detect residues down to parts per billion. To put that in perspective, that’s equivalent to one second in 32 years.” A tiny speck of residue from a combine hopper, a bin, an elevator or a shipping vessel could be detected and, if there is no MRL in place, could cause shipping disruptions.

MRLs have been around a long time, Dahl said, but testing equipment has become more and more precise. Because of this, zero has become too great a risk for exporters. What’s the answer? Dahl said grower groups and commodity organizations are working hard with Canada’s trading partners to avoid absolute zeros for MRLs and to improve communication throughout the value chain.

In the meantime, however, approved MRLs simply cannot be exceeded, Dahl said. “A rejected vessel at port isn’t just a huge cost for the exporter, Canada’s global reputation as an exporter could also suffer,” he said.

The ongoing issue with Manipulator is a perfect example of where the time lag between registration and MRL establishment caused a major headache for western Canadian farmers.

Manipulator, distributed by Guelph-based Engage Agro, is registered for use in Canada. However, the product does not yet have an MRL in one major market: the United States. This missing MRL with a major trading partner prompted an alert to growers in 2015: check with your buyer before using the product, as many exporters were not going to accept grain treated with Manipulator, and all elevators asked farmers to sign a declaration regarding its use.

Dahl said that while the MRL issue is a complex one internationally, there really are two simple ways to avoid a major issue. “Always read and follow label directions and, if there’s any doubt on the use of a product, check with your buyer first,” he said.

For example, while glyphosate has established MRLs in Canada and most of our markets, going in too early on a pre-harvest application could result in higher-than-acceptable levels of residue. This is because the chemical can migrate into the grain if the kernel is still maturing. Going in too early for pre-harvest application is going off-label and puts the resulting grain at risk of exceeding set MRLs.

TRADE, TARIFFS AND TECHNICALITIES

Gord Kurbis, director of market access and trade policy for Pulse Canada, is hopeful the MRL issue is one that the Canadian grain industry can get in

front of.

“MRLs set at zero aren’t necessarily compatible with trade,” Kurbis said. What’s more, exporters are often the entity that bears the risk of an exceeded MRL, but they’re not the ones with any control over the use of products or the establishment of MRLs. “Overall, farmers and industry are doing the right things,” Kurbis said, but there needs to be reasonable, predictable ways and means of dealing with MRLs.

What’s more, misaligned or missing MRLs are only going to become more of an issue as more free-trade agreements are signed, such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Canada-EU Comprehensive and Economic Trade Agreement.

“As more tariffs disappear, non-tariff issues like MRLs will matter more,” Kurbis said. “While misaligned MRLS, like a 10-ppm (parts per million) MRL in one country and a five-ppm MRL in another, can occasionally be a challenge, the key problem is missing MRLs. A missing MRL could default to zero or near-zero tolerances.”

The advantage of working through trade agreements, he said, is that we have the opportunity to establish rules to deal with these technical issues as they arise, ideally including recognition between trading partners of each other’s risk-assessment work and MRLs. “That way, if a country had a missing MRL, it could apply a trading partner’s MRL instead of defaulting to zero. This could solve a majority of the problems that arise,” Kurbis said.

In the short term, Kurbis said it’s vital that commodity organizations communicate with growers well ahead of the growing season. But the long-term goal has to be one of getting out to our important trading partners and securing the MRLs we need, Kurbis said.

“No one entity can solve this, so it’s important that commodity groups are working in partnership on the issue,” Kurbis said—which they are, both nationally and internationally.

KEEPING IT CLEAN

As both Dahl and Kurbis noted, the bulk of the issues with MRLs come down to two things: following label directions and communication. Kurbis said that the pulse industry has produced a grower advisory each year since 2011 to alert farmers to any potential MRL-related issues ahead of a new growing season.

Cereals Canada recently collaborated with the Canola Council of Canada, expanding on its Keep it Clean program to include grain-related reminders and considerations for growers (find it at keepingitclean.ca). The Keep it Clean initiative acknowledges not just in-crop considerations for crop protection use, but also covers storage best management practices, in an effort to minimize mycotoxin growth that could also have trade implications

(see sidebar).

The responsibility of the individual farmers, added Dahl, is to ask a few questions ahead of this growing season. “Before using a product for the first time, talk to your crop input supplier about any potential MRL issues,” he said. “Be sure to talk to your buyer about any MRL-related concerns.” MRL issues are highly dependent on where a product is headed, so one buyer may be more particular than the other.

And, as always, read and follow label rules when using crop protection products—entire export markets depend on it.

Comments