A DARK PRESENCE

BY TREVOR BACQUE

It may be thought of as a disease of the past, but ergot still causes headaches for farmers across the Prairies. While its prevalence may be high, its threat level is typically low and often a non-issue. However, the fungus that’s been a fact of life since at least the Middles Ages, remains a concern. Downgrades at the elevator and contaminated screenings cause issues for grain farmers and feedlot owners alike.

Simple to identify in a field, the collection of data on ergot occurrences is valuable. Every year, the Canadian Grain Commission’s (CGC) Harvest Sample Program analyzes quality characteristics of samples submitted by farmers from across the country and this includes the presence of grain diseases such as ergot.

Sean Walkowiak is keenly aware of ergot developments. A research scientist and program manager for microbiology and grain genomics at the CGC, he sees continued occurrences of the fungal pathogen but doesn’t worry much about it. “There is a trend. It may be increasing in incidence but perhaps not in severity,” he said. “It’s always been on the radar on our Prairies as well as anywhere else grains are grown. This is an issue in other countries.”

Farmers who submit to the Harvest Sample Program receive an unofficial grade and all specs related to their grain. Meanwhile, these samples provide CGC with valuable information about the overall quality of Canadian crops. The CGC has collated ergot trend data for the years 1995 through 2020. Analysis of the 230,000 samples collected during that period allowed CGC to rank the occurrence of ergot across the grains. Most affected is open pollinated rye, followed by wheat, durum, barley and then oat. It is also a threat to canary seed.

While contamination has always been present, there was a considerable difference in ergot occurrence between the 1995-2009 and 2010-2020 samples. Most notably, ergot presence in rye jumped to 65.6 per cent from 27.6. It also increased substantially to 19.5 per cent from 4.2 in CWRS and to 13.1 per cent from 2.9 in durum. Levels in barley and oat were negligible during this period. In his research, Walkowiak speculates the rise in the presence of ergot could be due to weather variation, germination rates of the disease and overall spore production. He points out, though, that despite increased numbers ergot has consistently posed the same level of median danger.

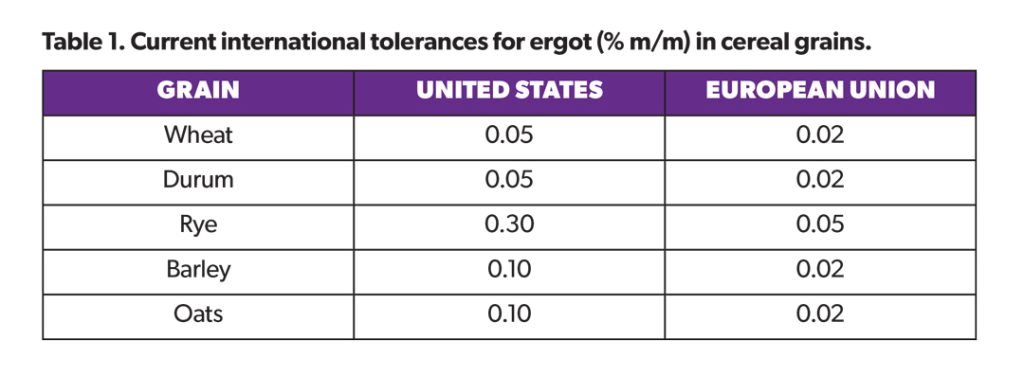

Standards have been developed for acceptable ergot presence domestically and globally (see Table 1). Canadian standards are close to the EU, which has the tightest regulations, regarding acceptable levels.

A soilborne pathogen, ergot thrives in wet, cool conditions and can live in the ground for at least one year, possibly longer. The presence of the disease becomes apparent at flowering when an orange-to-yellow substance commonly referred to as honeydew appears on infected florets. Certain insects consume it and inadvertently transfer ergot spores to healthy, neighbouring plants. Ergot honeydew is also spread by rain splash. At the peak of its damage, the pathogen goes on to replace an otherwise healthy kernel with oblong purple-to-black fungal bodies.

No commercial fungicides are available to control the disease. Agronomic wisdom typically suggests ergot management include continual mowing of headlands where disease inoculum can often collect, crop rotation that includes a non-cereal option, the use of clean seed and a watchful eye.

Because it has often been treated as a minor issue, scientific literature that pertains to ergot is minimal. “This is an area that really requires some additional research, because there really aren’t a lot of studies out there,” said Walkowiak. “A lot of the information on management is more anecdotal. It doesn’t get regular attention, but it might be time to revisit and do some good studies to look at the best management practices for ergot.”

Post-harvest, ergot can be cleaned, but usually costs 75 to 85 cents per bushel. The cost may be a few cents higher than this if it’s for seed. However, it may be worth the investment, especially if a farmer runs the risk of a downgraded delivery. It is possible to blend it off with a higher quality, clean crop.

Walkowiak said federal government protocols are effective. Assessed cargoes are never failed for contamination reasons and are always exported without issue.

“The grain grading system is working, and industry is doing a good job of cleaning it up when they need to,” he said.

FEED COMPLICATIONS

A level of primary risk does occur with grain screenings, which are often bought by feedlot owners in pallets and given directly to livestock. When palletized, the presence of ergot is difficult to detect on visual inspection.

At the University of Lethbridge, in the heart of Feedlot Alley, Kim Stanford works as an associate professor of biological sciences and focuses on food- and feedborne pathogens. She works diligently to track and monitor the impact of ergot in feed cereals within the cattle sector. One of the biggest concerns is the presence of ergot alkaloids, which can severely damage livestock health or even be fatal when consumed. She said even though 2023 was drier than average, ergot was detected in feed grain, which indicates farmers must monitor for its presence.

Regulations suggest animals should ingest no more than two to three parts per million ergot alkaloids, said Stanford. Feed companies can be prosecuted for selling unsafe feed if levels exceed three parts per million, she added. “Over three parts per million, you’re in big trouble. Even over two parts per million, probably you’re going to be in trouble.” Her most recent study demonstrated that 1.75 parts per million had no negative effects on the animals. “My finding that 1.75 was just fine doesn’t mean every feedlot that’s trying to feed 1.75 is fine,” she said. “They might run into problems. It’s difficult to work with and it’s better to err on the side of caution.”

Of course, zero per cent is not achievable and an unnecessary target. Feedlot owners feeding their animals any grain, but especially screenings, should simply pay close attention to their herd.

Research by Gabriel Ribeiro at the University of Saskatchewan determined livestock experience heat stress at 20 C and beyond when they consume more than three parts per million ergot alkaloids. “Twenty is not super-hot,” said Stanford. “As temperatures keep getting warmer, if ergot is making animals like cattle less able to thermoregulate, it’s another little problem.” Thankfully, there is a remedy. “The solution is just to blend it out so that you have much less concentration,” she said. “If you’ve got it less than one part per million in feedlot cattle, there might be a little bit of reduced intake, but mostly you are not going to run into problems.”

Such additional problems could include vaso-constriction of blood vessels due to high alkaloid presence. This will cause tissues to die, which can result in tails and ear tips falling off. It may also get into a cow’s hooves, which can cause the entire hoof to slough off, or the animal may appear lame.

TEST FOR IT

To confirm its presence and determine the concentration of ergot in grain, have it tested. In Western Canada, Prairie Diagnostic Services is available for farmers, said Stanford. A non-profit co-created by the Saskatchewan government and USask, it operates at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine on the university’s campus.

While some smaller outfits may perform a general test, PDS targets all six primary ergot alkaloids that negatively affect cattle. Because each alkaloid comes in two forms, R and S isomers, testing for both is critical. “It’s important to get R and S analysis,” said Stanford. “The problem is we’re working with very, very small concentrations of these alkaloids. Some of the research we’ve done lately shows that the analysis of the feed can vary up to one part per million just based on if you’re looking at a complete diet that would have silage in it versus just the grain. So, differences in pH are going to affect the analysis of these alkaloids. They’re very difficult to analyze.” Results are generally received within seven to 10 days.

Farmers can also feed alkaloid binders to livestock. These are typically clay-based. Stanford said it’s up to individual judgement whether the cost of such binders outweighs the risk to animal health. “The performance would have to be really a lot better to pay for the binder,” she said.

She reminds cattle farmers to trust their gut. If they see signs of ergot contamination, such as cattle being suddenly less interested in their feed, to deal with it immediately before it gets out of hand.

ERGOT RESISTANT DURUM A WORK IN PROGRESS

Canadian durum is of huge value to the export market. A recent Cereals Canada study determined durum wheat is responsible for the creation of 5,000 jobs and $1.1 billion in annual revenues. Its one glaring weakness looms over this strong market position. Not a single durum cultivar is resistant to ergot. The country’s top variety, Transcend, for instance, is susceptible. Much of Canada’s durum is exported, including to Italy, where it is used in pasta products. The dark colour caused by the ergot sclerotia is a problem for food processors and manufacturers. Customers want a bright, uniform yellow on store shelves.

Research is underway to create truly resistant cultivars and make them commercially available to Canadian farmers.

Yuefeng Ruan is Canada’s public durum breeder, and Samia Berraies, is a cereal pathologist hard at work to make this a reality. The two are in the midst of a four-year Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada project to develop one or more resistant cultivars. Their project began in April 2021 and will conclude by Aug. 15, 2025. Intensely aware of the necessity to produce high-quality cultivars, Alberta Grains contributed $60,000 of the project’s total $315,000 cost.

The project began on an optimistic note. Results from previous work on ergot resistance conducted at Swift Current provided a solid base to explore genetic factors that confer resistance. “The objective of evaluating durum genetic populations is to identify the regions in the genome that are associated with ergot resistance,” said Berraies.

Two durum wheat genetic populations were used for the study. Plants were challenged with ergot inoculum at the flowering stage. The reactions of the lines to infection was recorded. “The lines carrying the desirable genetic regions for ergot resistance were selected and used as parental lines and crossed with other durum-adapted materials in order to transfer those resistance genes in durum germplasm,” said Ruan. The researchers appear to have identified multiple winning genes, which will be bred into future crosses.

Ruan is hopeful the project will deliver new genetics to western Canadian farmers soon. “If we get more genes in one plant, then even in a really bad year, the plant will show much better resistance compared to the plant having less genes,” he explained. “For resistance, this is a complex trait, it’s not just one gene, it’s multiple genes.” They are working to identify as many genes as possible, a number they have yet to determine.

Like any disease, ergot pathogens evolve and mutate, so variety development will be ongoing. It is well worth the fight, given the protection it could provide Prairie farmers.

Berraies points out ergot tolerance regulations are increasingly strict around the world. This is a signal Canadian breeders must work hard to provide cultivar options for farmers so they can supply the international market.

“Those tighter restrictions can affect the trade market and the capability to export our wheat,” she said. “The need to develop truly resistant varieties for ergot in our breeding program is of paramount importance.”

Comments