JUST DO IT

BY TREVOR BACQUE • PHOTOS BY ZOLTAN VARADI

In 2024, another slew of Canadian farmers will transition out of farming while the next generation takes over either in part or whole. It’s a fact of farm life: eventually the farm changes hands. For countless reasons, farm transitions take many meandering paths. Depending on business and family dynamics, the trip can be smooth going or a rough ride.

The country’s farm economy continues to grow while the farm workforce out in rural Canada continues to shrink, and rapidly at that. Twenty-three years ago, the average Canadian farmer was 50 years old and there were 346,000 of them from coast to coast. While there is no official number for 2024, Statistics Canada data from 2021 showed the farmer average was 56, representing 60.5 per cent of all practitioners. The total number of primary producers dropped by 84,000 to 262,000 over that two-decade span, a decrease of 24 per cent. What’s more, a recent RBC study demonstrated that 66 per cent of Canadian farmers do not have a succession plan in place. The study’s lead author is Mohamad Yaghi. As part of his research, he surveyed more than 500 Canadian farmers, and discovered two-thirds had no plan for generational transition. The report predicts that in nine years’ time, 40 per cent of Canada’s current farm workforce will have turned over, with or without a plan. It will also drive a 24,000-worker shortfall unless action is taken. This affects the family farm, but also more labour-intensive farm operations.

Having heard from so many farmers, Yaghi understands the gravity of the transition process and knows it’s a big task for many to complete. “On an emotional and personal level, a lot of people don’t like to have this difficult conversation,” he said. “But if we don’t have the right measures in place to ensure the next generation can take over, it’s going to present some real issues to the country. Succession planning is really important because when you’re handing the farm down, you want to make it as clear and transparent as possible.”

It may pose a challenge to sit down as a family or bring in third parties who can assist in the process, but Yaghi labels it as necessary and insisted it’s a non-negotiable for any farm. Of course, not all farm children want to pursue agriculture as a career. Some may be more reluctant than their ancestors to do so, given the high cost of doing business in 2024.

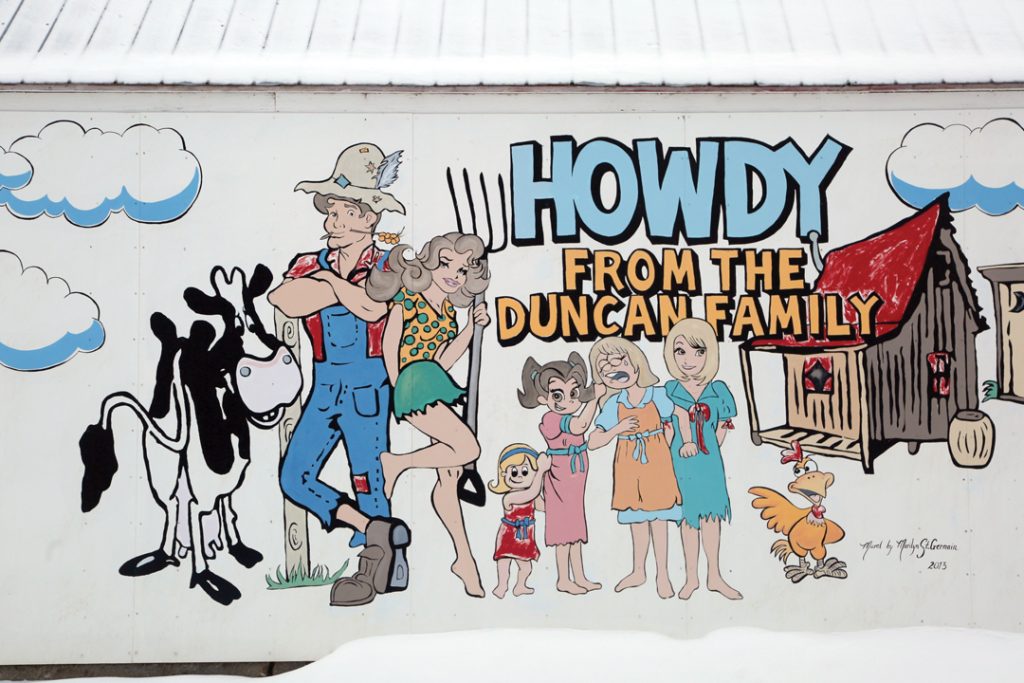

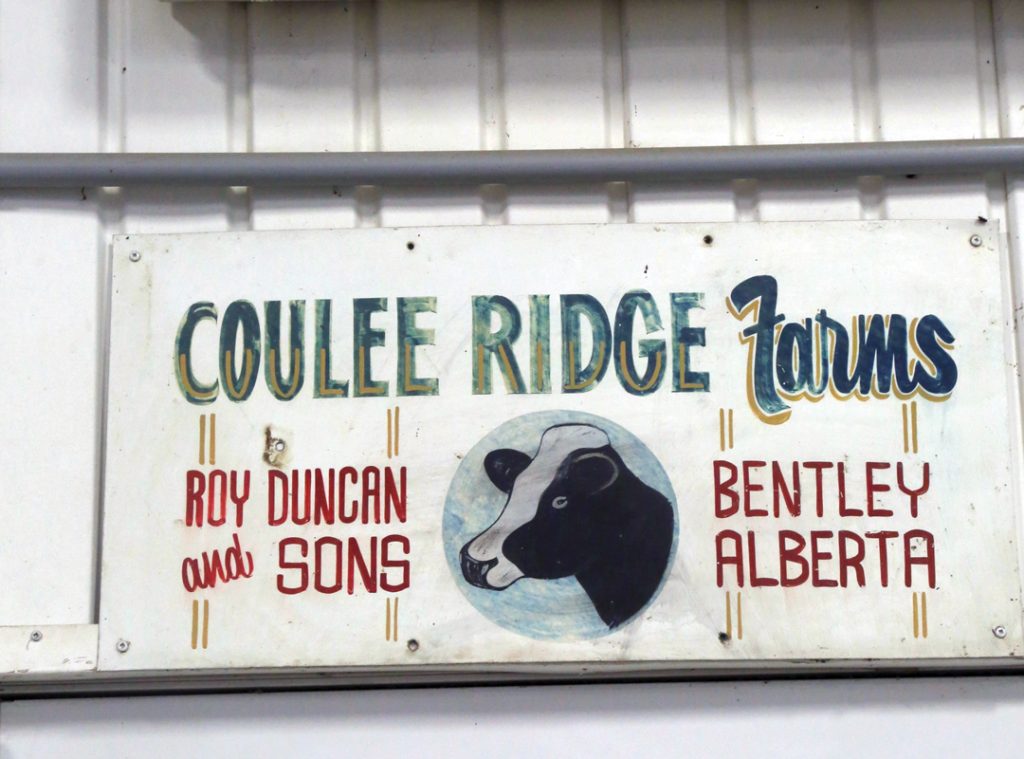

THE DUNCAN FAMILY FARM

Coulee Ridge Farms is located on the north shore of Sylvan Lake. Owner-operators Dennis and Laurie Duncan have recently completed a succession plan. Of the couple’s four adult daughters, two of them, with their husbands, will become the next generation to manage the farm. They are Shelby and Ty Lethbridge and Darci and Matt Cole.

The farmgate butts up against one of Sylvan Lake’s most popular boat launches. To fill the void following the sale of the dairy that had been central to the farm for decades, Dennis and Laurie created a boat winterization business. One year later, they launched an equipment shrink-wrapping business. Unrelated to farm transition, the thriving businesses were purchased independently by the two younger couples.

At 66, Duncan knows he does not want to run the farm business forever. He’s been in the driver’s seat now for a shade more than half his life, having fully succeeded his parents in 1990. In recent years, circumstances forced him to think about some of life’s realities. “We had a couple of close friends pass away, and you realize that it can happen to any of us,” he said.

Bona fide snowbirds, the Duncans were urged by their children to return home from Palm Springs during the pandemic for their own safety. It was the final push that got the succession process going. “I think COVID had a lot to do with it,” said Duncan. “That was a real mover to say, ‘Holy s—, we need to really get our ducks in a row,’ because this can happen. That’s something we all have to face: when do you start doing this? Not when you’re dead.”

The Duncans’ wills were written three decades prior when their daughters were all in their single digits, and it simply said in the event of death, sell all assets and divide by four. If this remained the case, the proposition may have been nightmarish given the desires and goals each daughter has regarding the farm.

Over the years, the family continued to chat informally about what a farm takeover would look like. Initially, the two non-farming daughters were fine to inherit land. However, as time went on, both decided it may be easier to take a financial payout. In contrast, the Coles and Lethbridges, who will operate the farm, will have all their equity in land, machinery and infrastructure.

The money was one of the biggest worries on Duncan’s mind, though, and he admits he didn’t want to dedicate much brain space to the subject, especially because of the capital gains taxes he believed would have to be paid on the appreciated land. “You don’t even want to deal with it or think about it,” he said. Duncan also had to mentally wrap his head around the realization that fair and equal aren’t possible if a farm is going to continue.

The two farming daughters have a disproportionate amount of equity in the farm, but without such an agreement, there would be no next generation. All four daughters understand this, and Duncan is grateful. “They realized that’s the direction you need to go in order to facilitate all of your mom and dad’s wishes,” he said. “Greed and all these other things play into this and can totally jeopardize and deep-six any forward movement on a farm transfer. So, my kids were fabulous that way.”

The Duncans had also given their daughters a questionnaire about the farm they had received from an insurance company. The questions evoked feelings about the farm from both an emotional and business point of view. It prompted them to picture what a reasonable future for the land could look like, and what role they may or may not play in it. A recurring word that became a theme during the transition was heritage. The daughters love the farm and want it to continue to honour the legacy created over the last 98 years. “All of them wanted to see it continue, and they would rather have a piece of the farm than money,” said Duncan.

Duncan noted the conversation shifted into “high gear” when his son-in-law Ty asked if he would finally become a farmer the day Duncan dies. What went unmentioned in the quip said it all. “Just that one statement was all it took,” said Duncan.

After harvest 2022, the conversations ramped up. The family enlisted the help of two farm advisors, Annessa Good at Farm Credit Canada and Don Oszli, a partner at Pivotal Accounting LLP in nearby Red Deer.

By early 2023, the two non-farming daughters had a change of heart. They had little interest in finding renters and upkeep and maintenance of their land. The two decided a cash payout was their preferred option. Their money will come in the form of a future sale of one quarter-section of land, which is eligible for development, that they share.

Even with co-operative children, Duncan admitted to feeling frazzled by even starting the process. He said Oszli was a life saver. After their return from Palm Springs last March, the Duncans sat down in Oszli’s office and began the process. Oszli has worked with hundreds of families throughout his four-plus decades in accounting. He asked the Duncans many questions about family history, established which members will be involved in the succession process and began to draft a roadmap.

In June, the Duncans returned to Oszli’s office. He presented a detailed inventory of their assets, an outline of the potential land transfer and a process to navigate capital gains taxes, which, again, was Duncan’s biggest worry. By the end of the meeting, a weight was lifted from his shoulders. “We came out of there with the biggest smile. We were like, ‘Wow, that was easy.’ He drew out an absolute perfect plan that we could give to the kids and say this is what we want to do.”

Families should budget at least one year to complete a farm transition, if not longer, Oszli recommends. Not surprisingly, the process becomes trickier when more than one child is involved. The process can simply begin with a conversation that involves incoming and outgoing generations.

“Sometimes you have to plant seeds,” said Oszli. “There has to be some communication and some type of a plan to facilitate the change. Oftentimes, it’s an education in financial literacy that needs to happen between father and child. Quite often dad has made the decisions, it’s all in his head, but to put a succession plan in place, it really needs to be in writing so both parties can understand where decisions are coming from.”

Having seen many clients simply start too late, he urges farm families that haven’t begun the process to begin today, even if it’s a quick, throw-something-at-the-wall conversation. “The neat part about the plan is there’s always different points we can make changes to, and if the plan needs to be looked at periodically, we can make changes as circumstances dictate.”

For the moment, the Duncans need no adjustment to their plan. The girls share collective gratitude for their parents’ well-considered efforts, which negated any heated voices, gnashed teeth or thrown chairs. “The farm is everything in my world, so to split it up would be tough,” admitted Duncan. “To have my kids fighting would be horrible, so I think they looked at all that and just went, ‘Whatever mom and dad want, we’re good with.’”

The sons-in-law even signed post-nuptial agreements that stated the farm itself could never be part of a settlement in the event of a divorce. Both men signed it with zero hesitation.

Duncan knows families that have been destroyed by greed when a child believed they were entitled to more than was offered. However, to ensure a farm continues to operate typically requires a disproportionate split of assets. “Let’s face it, there’s no question it is pretty lopsided,” he said of the farm transition. “It’s lopsided for the future of our farm to continue. You absolutely cannot look at numbers when you’re doing something like this. The old adage, equal is not fair, and fair is not equal; that’s a huge statement that really applies here.”

Nonetheless, the process was amicable and straightforward, said daughter Shelby. All four daughters are great friends and recognized the uneven asset distribution necessary to maintain the existence and operation of the family farm.

“Everyone was very friendly and just felt comfortable voicing any concerns if they felt something was unfair. But the way my parents did it, everybody kind of agreed it seems quite fair,” she said.

Now that the succession plan is in motion, it’s an exciting time for her family and sister Darci’s. With a clear path ahead, both families can envision long-term plans for the farm and its continued evolution.

Each sister will receive a set amount of land. The Lethbridges live on the home quarter with their parents and will receive outbuildings and houses but less land. The Coles have more land and live on a nearby acreage. The equipment is the only part of the farm that is owned jointly by the two sisters’ families as a corporation.

THE REAL THING

A self-described “hardcore farmer,” for many years, Duncan didn’t let on as to when he would start the succession planning process. His children were somewhat concerned it wouldn’t happen. “We’ve always felt like all these talks are great but is it actually going to happen?” said Shelby. “He always said, ‘In the next five years, in the next five years.’ But then years would go by, and it would still be, ‘in the next five years.’ It wasn’t until last year that things started to actually happen.”

The completed plan will see Duncan fully succeeded by the time he turns 70. As of today, each family has bought in at three per cent. Not monumental, but enough to make it feel real. “As soon as mom and dad put a plan in place as to how we’re going to move forward with this, I felt like that was the perfect solution. That’s what we needed to get the ball rolling, even if it’s slowly,” said Shelby. “It’s moving in the right direction. We’re learning a ton from working with my parents instead of just taking over all at once. I feel really good about the way it’s moving now.”

With the heavy lifting of the succession plan behind them, the real fun has begun for both generations. Shelby admits there were many career paths she and her husband could have taken, but the certainty they will be farmers is exciting and has practical implications. Ty and brother-in-law Matt can glean as much as possible from Duncan while he’s close at hand to mentor them. As well, Shelby loves the assurance her children will grow up to enjoy the same country lifestyle she did.

“The biggest thing is openness and communication by all parties,” said Duncan. “We put out there what we wanted, and they put out there what they thought of what we wanted, and in the end, it was just a smooth, very good process.

“When I’m on my deathbed and see my kids’ and grandkids’ names on those titles and that the farm is operating, I’m great, I’m done, I’m happy.”

Even though it was initially said of planting a tree, Oszli reminds farmers the best time to start this was yesterday, but the second-best time is today.

Comments