BLIGHT AT THE END OF THE TUNNEL

DREADED CEREAL DISEASE COMING SOON TO A FIELD NEAR YOU

BY GEOFF GEDDES

At the movie theatre, trailers for “coming attractions” are designed to whet your appetite. Unfortunately, for many years in Alberta, the most hyped “coming attraction” in the agriculture world was a rapidly spreading cereal disease with an appetite for destruction. After scathing reviews in other provinces, the B-movie thriller known as Fusarium head blight (FHB) is taking Alberta by storm, and producers have a front-row seat.

Also known as “scab” and “tombstone,” FHB is a fungal disease that affects wheat, barley, oats and other small cereal grains, as well as corn.

“It is caused by a range of Fusarium species, but the most damaging one is Fusarium graminearum (F. graminearum),” said Kelly Turkington, a plant pathology research scientist at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s Lacombe Research and Development Centre.

In the mid 1980s, F. graminearum was rare in Western Canada. However, the situation soon changed.

“1993 was a watershed year for F. graminearum,” said Turkington. “Prior to that, it was found mostly in Manitoba and states like North Dakota and Minnesota. Suddenly it was being detected more frequently in Fusarium-damaged kernels in eastern Saskatchewan in the late 1990s, before spreading west and into Alberta.”

By the early 2000s, Fusarium became more prominent in southern Alberta, causing an increase in issues with grade reduction. Then, five years ago, the disease made its way to central Alberta and beyond.

HITTING CLOSE TO HOME

Now that F. graminearum has become more of an issue in Alberta, FHB risk maps are in the works. The Alberta Wheat Commission (AWC) will provide initial seed funding to get the map project up and running. Brian Kennedy, grower relations and extension co-ordinator with AWC, is spearheading that effort.

“The map isn’t a definitive tool,” said Kennedy. “It provides more data and awareness to growers to inform their decisions.”

If all goes as planned, there may be pilot maps available to producers by next summer. “We need to review weather and F. graminearum data from the last couple of years to validate the model for Alberta,” said Kennedy. “Getting the maps out is important, but we’d rather release no information than bad information.”

Although the current focus is on developing a map for wheat, it’s hoped the project can be modified for barley once a working model is established, said Garson Law, research manager for Alberta Barley.

MAP READING

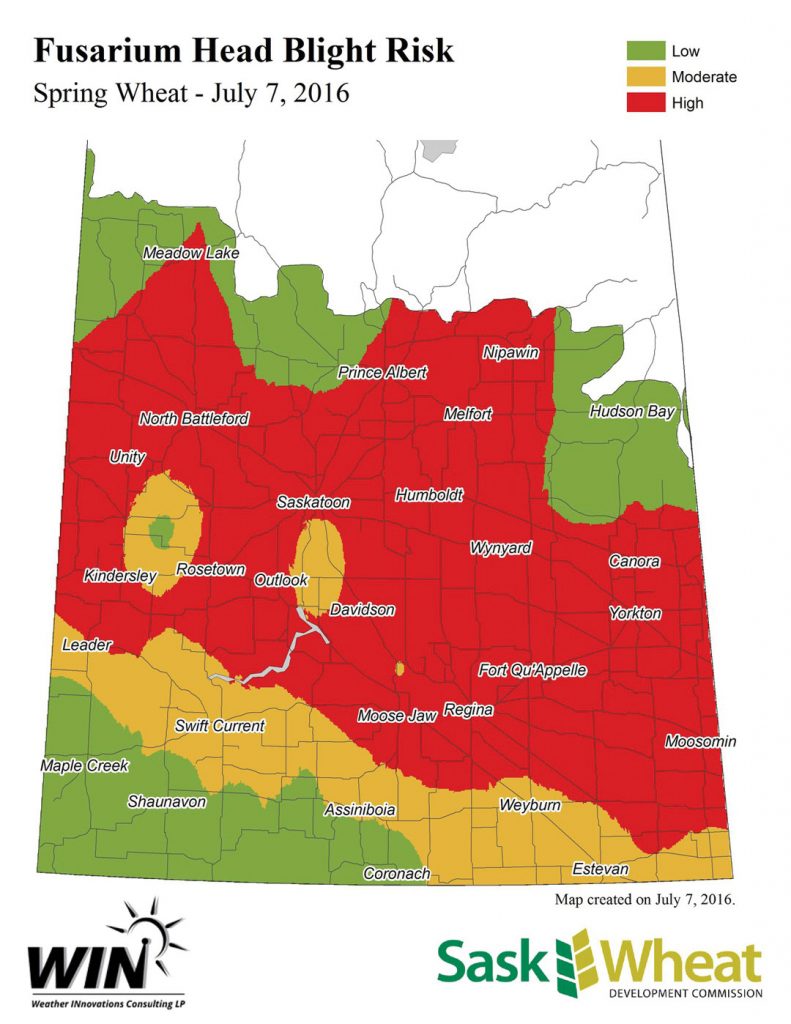

FHB risk map have been used to help battle F. graminearum in other regions where the fungus has long been an established problem for farmers. They have been available in Manitoba and parts of the United States for several years, and the maps were added to Saskatchewan’s arsenal by the Saskatchewan Wheat Development Commission (Sask Wheat) two years ago.

“Our board received a strong message from producers that more resources were needed to help manage FHB,” said Harvey Brooks, general manager of Sask Wheat.

Identifying areas of the province as high, medium or low risk, the maps—posted on the Sask Wheat and provincial government websites—indicate whether weather conditions are favourable for the development of F. graminearum.

“Farmers located in zones with the requisite moisture and high nighttime temperatures to warrant a ‘high risk’ or ‘medium risk’ label should be checking their crops and weighing their management options,” said Brooks. “Plants can’t get infected until flowering, so if they’re at that stage and conditions are risky, there is additional material online to guide producers through critical spraying decisions: whether to spray, which fungicides are approved for use with F. graminearum and the best times to apply them.”

Although he also advocates use of the maps, Mitchell Japp, provincial specialist for cereal crops with the Government of Saskatchewan, agrees with Brooks that farmers should use multiple resources to determine how they will limit F. graminearum infection. “The map is a good starting point to indicate if there’s risk, but no tool is perfect,” he said.

Japp stressed that farmers still need to be in the field getting a sense of what’s happening and factoring in local conditions. “If you are at high risk when the crop head is emerging, which is when the crop starts to become susceptible, it doesn’t mean you should spray. Farmers must consider many factors, including whether they or their neighbours have had FHB before. They should look at what stage their crops are in, check the weather, factor in the cost of applying fungicide, estimate their crop yield and decide if applying fungicide will provide a positive return on their investment.”

SINGS OF THINGS TO COME

If you’re worried that a child has chickenpox, you look for spots. But how do you spot FHB in your crops?

“Symptoms in wheat initially appear as dead, prematurely ripened portions of the cereal head affecting one or more spikelets,” said Turkington. “With severe infections, the entire head may prematurely ripen and there will be a brownish discolouration of the stem directly below the head.”

Although the symptoms are similar for barley, Turkington said, “head and kernel symptoms in barley are much less distinct and can be easily confused with diseases such as spot blotch and kernel smudge, or even hail damage.”

While knowing what to look for is crucial, knowing when to look is also important.

“One of the best times to scout for head blight on cereal crops is at the late milk to soft dough stages, because the healthy tissues are still green and the infected tissues, which appear bleached, are clearly seen,” said Michael Harding, a plant pathology research scientist with Alberta Agriculture and Forestry.

BRACING FOR IMPACT

Turkington warned that it is dangerous to treat Fusarium just like any other run-of-the-mill cereal disease, given the negative consequences it can have on producers’ bottom lines.

“I’ve always emphasized to producers and industry that Fusarium is unlike any other disease. Not only can it cause yield and grade reductions, but what really sets F. graminearum apart are the mycotoxins it produces, which are harmful to both animals and humans. Whether producers are focusing on feed or food, the damage to end-use marketability can be devastating,” he said.

That view is shared by Harding, who added that, “while yield loss is a concern, the greatest impact is downgrading.”

This is borne out by a recent economic impact study conducted by the Alberta government, which examined the potential effects of Fusarium infection in a field of Canada Western Red Spring (CWRS).

“At just 0.4 per cent disease prevalence, the total revenue loss from reduced yield and a class downgrade from No. 1 to No. 2 is about $52 per acre,” said Harding. “When the wheat is downgraded further to No. 3 or feed wheat, the economic impact increases significantly to $62 and $65 per acre, respectively.”

Over the last five years, depending on the value of No. 1 wheat in a given year, that translated to losses in the millions of dollars for Alberta farmers. For example, in 2012, a large amount of CWRS production—more than 400,000 tonnes—was downgraded from No. 1 to No. 2, with a small amount further downgraded to No. 3. Since the price discount is fairly low, the total provincial cost was a relatively modest $3 million.

That cost was much higher in 2010, when a smaller amount of production was downgraded, but the grade drop was more severe. This time, all the downgraded grain dropped to No. 3 or feed wheat at a total cost of about $8.7 million, according to the economic impact study.

However you crunch the numbers, that’s a lot of money, and CWRS is just one of many crops affected by Fusarium. Few would argue that it’s a disease unworthy of special attention, but what exactly does that entail?

MANAGEMENT TRAINING

The answer came in 2002 when, after an extensive public consultation process, Alberta Agriculture and Forestry released the first comprehensive Alberta Fusarium graminearum Management Plan. The plan was designed to limit the introduction, escalation, spread and economic impact of F. graminearum in Alberta.

It included input from the province’s Fusarium Action Committee, which is composed of several industry groups, including Alberta Barley and the Alberta Seed Growers. The committee’s mandate is to represent the interests and views of Alberta’s agricultural industry regarding the management of F. graminearum; recommend management strategies; and educate Alberta’s crop and livestock industries about the disease and the threat it poses to producers, processors and other stakeholders.

“We cannot take a wait-and-see approach to management of this disease,” said Harding. “By the time symptoms appear, it is too late to apply management tools other than trying to remove Fusarium-damaged kernels from harvested grain. Nearly all management tools must be implemented prior to seeing symptoms.”

Ultimately, producers must take an integrated approach that employs as many tools as possible. “For diseases like blackleg or scald, there are highly effective management techniques to mitigate the risk,” said Turkington. “With F. graminearum , you can use all the tools and still have significant yield loss, grade reduction and mycotoxins.”

DURUM DILEMMA

As if the basic challenges presented by F. graminearum weren’t enough, the obstacles to effective management are even greater when it comes to durum.

“Durum has historically been very susceptible,” said Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) research scientist Ruan Yuefeng.

“F. graminearum is generally assessed in terms of incidence (number of spikes affected), severity (amount of spike tissue involved with the disease) and the effects on the grain, which we measure as a proportion of Fusarium-damaged kernels,” added Yuefeng’s colleague, AAFC biotechnologist Ron Knox. “Durum tends to be higher in all three aspects.”

Both men stressed the importance of selecting the most resistant varieties of durum. “Even though they can get infected as well, you want to reduce the favourability of conditions for the disease,” Knox said.

SEEDS OF DISCONTENT

One sector being hit hard by F. graminearum is the seed industry, which is being hurt by the disease itself as well as the provincial regulations designed to control its spread.

“With current regulations having zero tolerance for F. graminearum, samples must be treated and cleaned for the disease, leaving less genetic material to go around,” said Kelly Chambers, executive director of the Alberta Seed Growers.

“Even if the seed goes in clean, unless it’s a resistant variety you likely have inoculants sitting in the soil,” she added. “Under the right conditions, you will have F. graminearum develop, and without the province recognizing that, it impedes the education process.”

Consequently, Chambers said producers feel they don’t have to worry about the disease and may manage accordingly, causing it to spread more rapidly.

One of the best tools for controlling the disease’s spread is the use of Fusarium-resistant varieties, but that is easier said than done in Alberta’s regulatory environment.

“Unfortunately, it’s that chicken-and-egg dilemma. If we stick our heads in the sand and say ‘zero tolerance,’ we won’t open doors for genetics coming to Alberta that could offer resistance,” she said. “It’s perceived that we don’t need those genetics because we don’t have Fusarium here, so the provincial stance is a big obstacle to combating this disease.”

Comments