DISEASE DETECTION MADE EASY

BY IAN DOIG • PHOTOS COURTESY OF RILEY MCCONACHIE

AI is rapidly being incorporated in a wide range of agricultural uses from chicken egg sexing and apiary management to in-field crop analysis.

University of Guelph graduate Riley McConachie recently earned a master’s degree in plant agriculture and credits his advisors with suggesting he use newly released AI technology in his thesis project. This prompted his idea to combine the use of Meta AI’s Segment Anything software with remote sensing technology to evaluate crop disease.

With help from the University’s research and innovation office, he received a grant to create an easy-to-use mobile app to detect Fusarium head blight in wheat crops. The as-yet-unnamed tool is at the prototype stage. Though it likely won’t be ready to tackle the 2025 spring crop on the Prairies, McConachie hopes it will be available to evaluate eastern Canadian winter wheat crops. Once necessary field testing is completed this year, a full release in spring 2026 is likely.

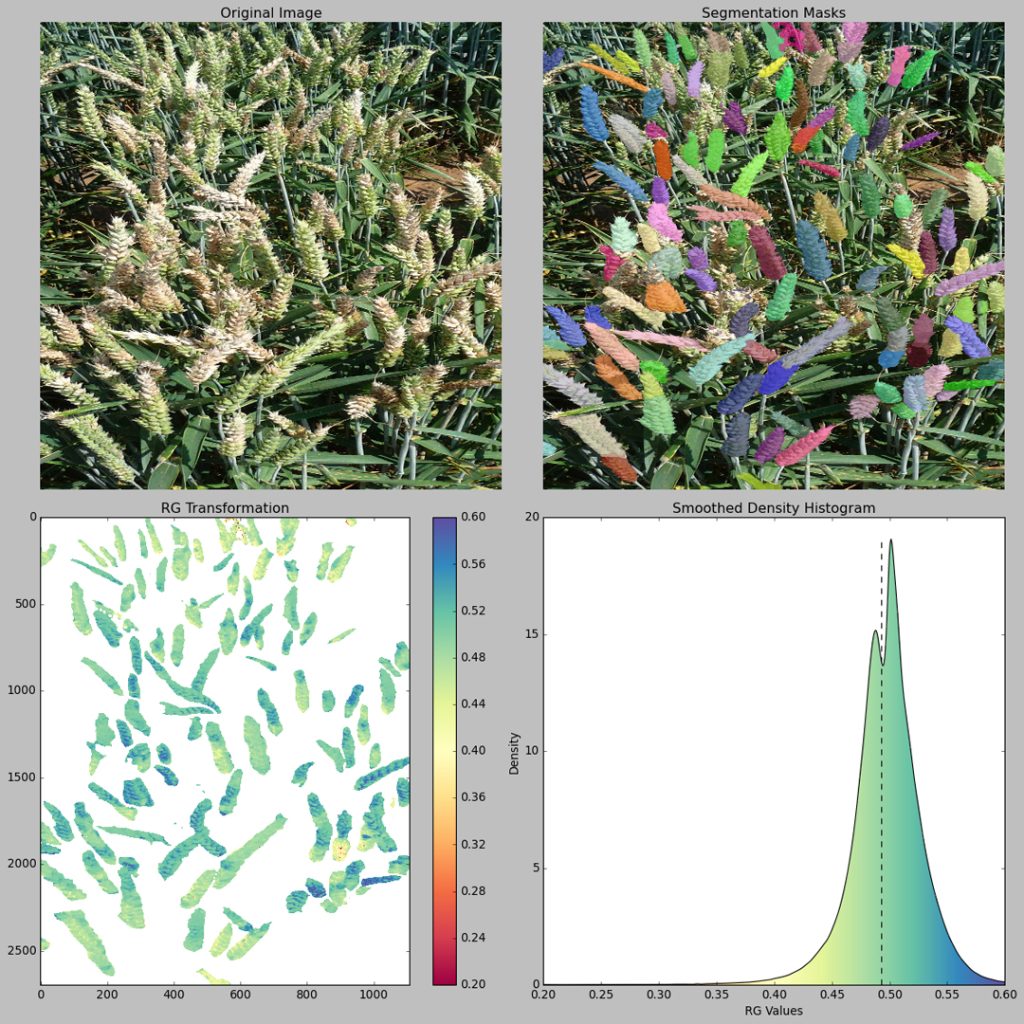

To use the app, a farmer takes photos of several approximately one-square-metre sections of a wheat crop. The AI isolates every wheat head in the image, colour codes it with the use of the spectral index and calculates the percentage of infection visible within the image. “That way, the farmer can alter their harvesting techniques to try and minimize the impact of the pathogen,” said McConachie.

He stressed it is important to remember AI, which is shiny and relatively new and receives a lot of hype, is not always the best solution to every problem. “Slight lighting changes can really mess with these AI models quite a bit,” he noted. His app makes relatively simple demands of its AI component: find the wheat heads in the photo and do the math required to colour code them for signs of disease. The task is easily adjustable for light conditions.

The tool can be used by farmers and agronomists but is also well suited to crop breeders. In its nursery, the University of Guelph wheat breeding program artificially infects wheat plants with Fusarium to gauge their resistance. The app makes the assessment of such disease plots more efficient. “It’s a lot less time consuming and more accurate than assessing them by eye,” said McConachie. For the past two years, McConachie has photographed these disease plots to collect field data that will contribute to his PhD research. The app’s assessments have closely matched visual assessments. “Overall, we’re very happy with the results,” he said.

This summer, Ontario’s Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs will incorporate the technology McConachie has developed—not the app itself—in the work of its Great Lakes Yield Enhancement Network. The initiative is intended to assist winter wheat farmers close the gap between actual and potential yield.

In the future, McConachie also intends to incorporate head count capability in the app as a yield estimate indicator. Fine-tuning of infection data by field zone is another potential area of exploration, and a fellow master’s student in his department is at work on scaling the technology up for use with drones and satellites.

Comments