ENDANGERED SPECIES

BY TREVOR BACQUE • LEAD PHOTO COURTESY OF AAFC

Prairie farmers continue to deal effectively with grain diseases of all kinds. This is due to an efficient new variety pipeline, access to certified seed and a host of crop protection products and cultural practices. Reassuring as this is, farmers must remain vigilant in the fight against crop diseases such as Fusarium head blight, rust, bunt and smut. Likewise, researchers work to produce resistant varieties and create tools so farmers can curb incidence rates.

Over the last 36 years, James Menzies has had much experience with grain disease on the Prairies. The federal plant pathologist at the Morden Research and Development Centre in southern Manitoba has focused his research on ergot in wheat, crown rust in oat and smut in small grain cereals.

As long as farmers have grown grain in this region, they’ve contended with smut. However, it’s been largely under control for several generations. From the late 1800s until about the 1950s, smut devastated crops without much recourse. Losses of up to 75 per cent were regularly reported until science developed countermeasures.

“The advent of resistant cultivars, fungicide seed treatment, certified seed; all of these factors working together means the smut pathogens don’t cause very much loss at all,” said Menzies. “I wouldn’t say cases of smut are uncommon, but it would be uncommon for them to cause greater than a trace loss in any cereal crop.”

Menzies does encounter reports of fields that have 25 to 35 per cent loss due to smut. The visual clues are often not spotted until it’s too late. As well, because there are multiple types of smut, it’s important to note which type you’re dealing with in a field (see sidebar). Smut does not drastically affect or delay crop growth, so it is near impossible to detect until late anthesis. “During late anthesis, go and walk through the field, if you have smut you’ll see it,” he said. If present, grain heads will be replaced with masses of black teliospores. Walking through an infected field, these will blacken one’s pants.

To calculate the loss is quite simple, as well. The infection rate typically equals yield loss. Twenty per cent infection? Twenty per cent yield loss. If your grain is substantially downgraded or outright rejected by an elevator, it can be sold as animal feed. Livestock can process smutted grain with minimal to zero associated health risks, said Menzies.

Fortunately, smut is easier to manage than other fungal diseases. Smut seed treatment fungicides are readily available to farmers, noted Menzies. Though outbreaks can have a frightening appearance, he added, the appearance is almost always worse than the actual infection rate. He has inspected fields that at first glance appear to be 90 per cent infected but turn out to be just 10 to 35 per cent affected.

To determine the level of infection, Menzies advises you check three or four areas in a given field. Construct a square metre with rope or PVC pipe and get to work. Count 1,000 or 2,000 heads. “While you’re counting, keep track of the number of those heads that are smutted, and that will give you your level of infection.” Twenty smutted heads, or two per cent, is a bad number, but one in a thousand, would be deemed trace level infection.

The three chemistries typically used against smut are difenoconazole, carbithiin and triazoles. Perhaps the most used fungicide is Group 7 product carboxin, which has high efficacy. There are documented cases of fungicide tolerance or resistance to this product in smut, though. Despite this, Menzies said it remains a very good option and resistance cases are minimal. He does remind farmers to rotate fungicide modes of action when possible and apply only when necessary. If you skip the application of a $200 per acre fungicide seed treatment because you’re only losing $100 per acre by the smut, he said, you’re still ahead $100.

In addition to seed treatments, farmers can guarantee a quality product by purchasing certified seed, which is tested for smut. “Really, the problem usually arises because farmers use their own seed to re-seed,” he said. “If you’re going to do that, you have to monitor your crop the year before.” This will eliminate a surprise occurrence of smut. “If you have high levels of smut, you probably shouldn’t use that crop, or you should use a fungicide seed treatment on that seed. Re-using seed is probably the number 1 culprit for having smut issues. It just gradually builds up.”

Which type of smut do you have?

Prairie farmers must be mindful of six smut types

Corn: Large growths, or galls, form from the inside out of a mature ear of corn. The discoloration is often bluish-blackish, sometimes with a burnt appearance. In certain countries such as Mexico, smutted corn is a delicacy and contains more protein than non-infected cobs.

Wheat: Loose smut infects wheat plants during flowering. Infection can be transmitted by insects, rain droplets or wind. As the disease matures, infected plant heads blacken. Spores blow away or fall off and grain is left headless.

Barley, True loose smut: Similar to wheat, brown or black heads replace healthy grain kernels. True loose smut does not affect a barley plant’s ability to germinate. Typically, flowering spikes are not visible once they’ve been replaced with fungal spike spores. These will rub off on your pants during in-field scouting.

Barley, False loose smut: Typically visible at the heading stage, this smut is characterized by dusty, black-brown heads. Largely identical in appearance to true loose smut, under a microscope, its unique teliospores are oblong.

Covered smut in oat, barley and rye: Covered smut on all three cereals typically emerges as hard, dark brown or black galls. They can be covered in a white-grey outer shell, which differs from other smut types. These galls stay on the plant longer than other types.

BATTLE THE BUNT

Common bunt was also once prevalent on the Prairies. It has largely been brought under control by fungicide seed treatments and resistant cereal varieties. While it occasionally troubles organic farms, conventional operations almost never experience outbreaks. Ominously, when infection does set in, it can quickly devastate a crop and spores may live for multiple years in the soil.

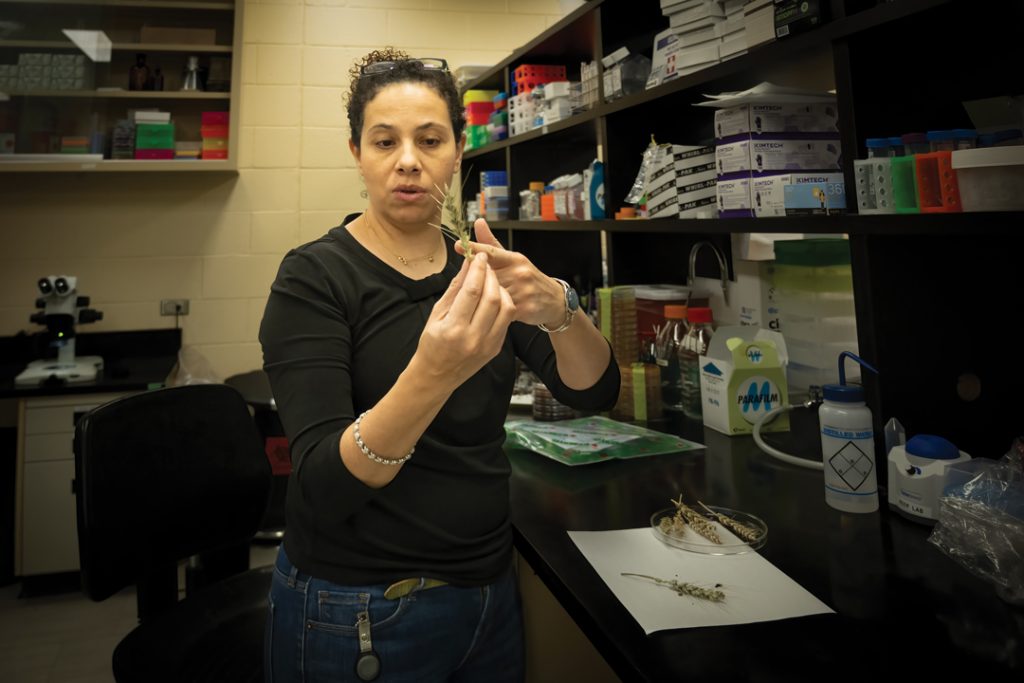

In Lethbridge, federal cereal pathologist Reem Aboukhaddour has operated a bunt nursery for seven years. The facility annually exposes hundreds of wheat genotypes to bunt.

You must have a keen eye to spot bunt, she said. Aptly named, the infection is covered under a plant’s intact glumes, and symptoms become evident only after heading. They can remain undetected until harvest. The fungus grows systemically and replaces the potential kernels with masses of black teliospores that are contained under the glumes.

Despite known controls, bunt remains a priority 1 disease for research scientists, along with Fusarium and all types of cereal rust. Aboukhaddour joked that bunt is treated like a second-class citizen in the disease world, but farmers and scientists best not ignore it. “Any little contamination of infected seed can ruin a big shipment of grain,” she said.

While it diminishes yield, bunt infection causes significant quality losses, even at low levels. In Canada, grains contaminated with bunt spores at levels of 0.01 per cent or higher by weight are downgraded to animal feed. Livestock, however, do not like bunted grains. Grain handlers reject bunted grains for fear it will contaminate their systems.

The infected grain is most easily identified by smell. Infected heads crushed between a person’s thumb and index finger release the unmistakable fishy odour of trimethylamine. The appearance of bunt, once fully developed, is striking. The spores, or bunt balls, are particularly hard to deal with if no seed treatment is applied, because the fungus is known to infect the emerging seedling below ground and grows alongside the plant’s maturing tips. The fungus prefers the cool six to 10 C range. Under cool temperatures the spores germinate, and slower plant development enables the fungus to reach the growing point of the plant prior to stem elongation. In warm soil, plants can escape the infection as they outgrow the fungus.

“Outside, you see the plant as normal, but when the head forms, you start to see some sign of the infected grain. It’s not easy to tell infected plants from non-infected ones. The fungus will form a lot of spores and hijack all the grain.” As the crop emerges from the boot, farmers can observe a bluish-greyish spike, rather than a healthy light green. Crushed heads appear black, and that is the bunt ball inside the infected head. “Usually they make the tiller shorter, and the awns are more outward than inward,” added Aboukhaddour. “There are some clues, but it’s not easy to determine without training.”

Bunt has been found across Canada and the U.S., but the Pacific Northwest and the Canadian Prairie are hot spots for infection. This is attributed to the higher elevation, high snow accumulation and cool spring. In Lethbridge, Aboukhaddour and her team regularly test genetic material for western Canadian breeders from government agencies, universities and the private sector.

Thousands of spring and winter wheat lines are tested annually, each over the course of three years. A line receives a rating to match its worst performance, with environmental factors being considered.

A farmer who suspects a crop may have bunt should scout in the early morning or afternoon—never during the middle of the day—as it is not easy to spot the difference between healthy and infected heads.

Aboukhaddour noted people regularly confuse loose smut and bunt. This is because they are closely related diseases that originate from the same group of fungi and form black spores. In loose smut, however, spores are not contained under the intact glumes.

Unlike rust, bunt does not travel on the wind, which is a huge plus for farmers. When infection occurs, it’s localized and doesn’t necessarily spread quickly. However, machinery contamination may be an issue, and disinfecting equipment is not an easy task as the spores are lightweight and can persist in hard-to-reach places.

Common bunt spores can remain viable in the soil for up to three years. The most effective forms of control are certified seed, fungicide seed treatments, crop rotation and the selection of varieties with adequate genetic resistance, said Aboukhaddour.

ONGOING BUNT RESEARCH

At the Swift Current Research and Development Centre, Firdissa Bokore leads a team of research scientists in the development of common bunt resistance in CWRS wheat varieties. He stepped into the role following the retirement of longtime research scientist Ron Knox.

Beginning in December 2020, the project entitled, “Marker assisted breeding for common bunt resistance in new wheat varieties adapted to the Canadian Prairies,” is slated to wrap by September 2025. Funding partners include Saskatchewan’s Agriculture Development Fund, Alberta Grains, the Western Grains Research Foundation and SaskWheat. Its primary goal is to boost bunt resistance by gene stacking in CWRS wheat.

The project generates crosses of elite bunt-susceptible CWRS lines with bunt resistance sources for marker-assisted selection. Markers are useful indicators, often within the plant’s DNA, that indicate the presence of a specific gene. Beyond this, the researchers have applied breeder-friendly markers of bunt resistance in breeding lines to improve upon, or validate, future markers. These markers allow breeders to work faster and more efficiently because they indicate which varieties contain desirable genes. From there, they can simply crossbreed these with other promising varieties.

Bokore said there are lots of high performing wheat varieties out there, but their genetic makeup may not be entirely known. He points to recent studies at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Swift Current that identified several common bunt resistance genes in cultivars Lilian, Carberry and AC Cadillac that could be pyramided into a single variety. Recently developed varieties such as AC Brandon—now the dominant CWRS variety—lack sufficient resistance to bunt.

“We need molecular markers to pyramid the genes in our newly developed varieties or in our breeding program,” he said. The current project funds, for instance, facilitated the development of new DNA markers for 12 bunt resistance factors, or genes, identified in various chromosomal regions of adapted CWRS cultivars.

By understanding where molecular markers are located and what traits they are associated with, breeders can better track the genes and build upon these traits by stacking additional positive traits on top of them. The markers flag the genes and make the work of scientists that much easier and will produce higher performing varieties.

“We use those markers to test thousands of breeding lines, and we don’t need phenotyping or field analysis to do that,” he said. “It just reduces the cost of field evaluation as lines carrying susceptible genes are discarded.”

Newly developed markers are tested and verified in National Research Council labs. The markers developed by Bokore and his team will be additionally used in marker-assisted selection by the Swift Current wheat breeding program.

His lines are also sent to New Zealand to multiply early generation seed to accelerate the work. “Breeding is a long process. We are not expecting varieties registered right away after this,” he said. “We are just getting elite lines that can go into testing for registration.”

Through Bokore’s research and end goals, there is reason to believe future generations of spring wheat will only get better. This is good news for Canadian farmers who continue to grow a majority of CWRS in their fields.

Comments