COMEBACK CLASS

BY MELANIE EPP • PHOTO COURTESY OF HARPINDER RANDHAWA

There was a time when Canadian Western Hard White Spring (CWHWS) wheat was touted as the next big minor class. Today, though, the class is virtually dead. Despite having lost its shine, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) wheat breeder Harpinder Randhawa believes CWHWS is poised to make a comeback thanks to a new, higher yielding variety he developed. While AAC Whitehead yields 21 per cent higher than previously established CWHWS varieties, industry experts believe it will take more than yield to revive the class. If the history of CWHWS has taught any lessons, it is that marketing, competition and quality all play a crucial role in determining the success of a wheat class. However, GrainsWest recently spoke with farmers and scientists who are cautiously optimistic about its return.

CWHWS: A HISTORY

The story of CWHWS begins in the early 2000s with two newly developed varieties, Snowbird and Kanata. According to a presentation by Graham Worden, who was senior manager of technical services at the Canadian Wheat Board (CWB) at the time, both varieties were developed using CWRS genetics. FarmPure Seeds owned both varieties and worked in partnership with Paterson Grain and the Canadian Wheat Board Identity-Preserved Contract Program (CWB-IPCP) to develop a market.

In 2003, production reached 190,000 tonnes, and quality was excellent. In the following year, production rose to 600,000 tonnes. Quality, however, was compromised due to a poor growing season and challenging harvest weather. In 2005, production increased to nearly one million tonnes. Again, quality took a hit due to poor harvest conditions.

Snowbird’s sister line, Kanata, was slower to develop. In 2005, production reached around 40,000 acres.

The success of CWHWS at that time can be partly attributed to the CWB-IPCP, which initially offered a contract premium of $7.50 over CWRS. On top of that, protein premiums were introduced for the 2004/05 growing season.

Under the 2005/06 program, farmers received a contract premium of $2.50 over CWRS, including protein premiums. The program offered guaranteed acceptance and delivery and escalating storage payments. Farmers were also eligible for CWB pricing options. N. M. Paterson & Sons and Cargill handled 90 per cent of CWHWS grain at that time. Six additional partners handled the remaining 10 per cent.

Under the 2006/07 program, farmers were offered a contract premium of $2.50 over CWRS (including protein levels). That season, however, guaranteed acceptance and delivery was limited to 300,000 tonnes. In the previous two seasons, acceptance and delivery had been guaranteed.

Snowbird yielded five per cent more that Kanata, but Kanata matured slightly quicker than Snowbird, making it more suitable to northern wheat farmers.

CWHWS target markets included Asia, North America and South America. End-users were impressed by its quality, particularly in 2003, recalled Lisa Nemeth, director of markets, Canadian International Grains Institute (Cigi), the technical division of Cereals Canada. “There was excellent feedback from customers about the quality of it, and a lot of excitement,” she said. Weather challenged farmers in the following years, and the class acreage declined significantly and never really recovered, she added.

Still, customers in the Asian market were fans of the class, but they required consistent volume to justify shipping costs. Canadian farmers, at that time, were in competition with their Australian counterparts who won the shipping battle by sheer proximity.

Price was also an issue, as Canada couldn’t match the market price, which was driven by Australia. “The single variety just couldn’t sustain the need for consistent volumes,” said Nemeth. “Producers moved away from growing it because of these challenges.”

Western Canadian farmers produced a little more than 7,000 insured commercial acres of CWHWS in 2020. Smaller Canadian mills purchase it for sale in niche markets.

AAC WHITEHEAD SEES CONSIDERABLE YIELD BOOST

Over the years, CWRS varieties continued to show improvement while CWHWS was left behind. Nonetheless, AAFC’s Randhawa set out to create an improved CWHWS variety. His quest proved successful. AAC Whitehead produces 21 per cent greater yield than previously established varieties and comes with an excellent disease package that includes leaf rust, stem rust, stripe rust, Fusarium head blight and common bunt. It is semi-dwarf in height with very strong straw.

“It’s agronomically flawless and very competitive to CWRS varieties,” said Randhawa. It also has the Sm1 midge tolerance gene, but must be blended with a midge-tolerant variety to protect the genetics from being overcome in the future, said Randhawa.

Before being accepted for registration, AAC Whitehead passed stringent quality committee tests. Nemeth was on that committee.

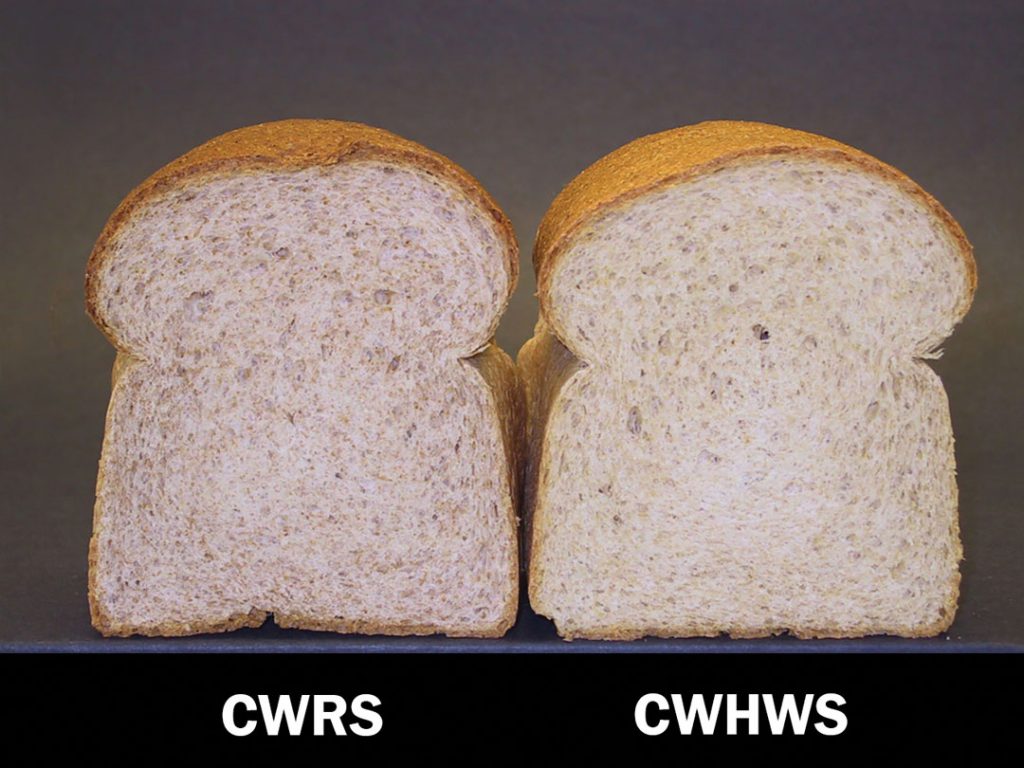

Quality-wise, CWHWS is very similar to CWRS but has a white seed coat. Certain end-users prefer such a white seed coat because it visibly reduces the appearance of specks of bran in the flour. “The bran has a lighter colour and, therefore, it is less noticeable,” said Nemeth.

Certain consumers, she said, find whole wheat bread made from white wheat more visually appealing due to its lighter colour. Others find the sweeter, nuttier taste of its white bran appealing. Those sensitive to the taste of bran find red bran more bitter.

Lighter bran is also desirable for end products such as noodles. When used in noodles, the redder bran particles become more visible over time due to oxidation, said Nemeth. This is much less noticeable when white wheat bran is used.

MULTIPLE LICENSED VARIETIES

Herman Wehrle is director of market development for FP Genetics, a farmer-owned, Western Canadian certified seed company with an interest in hard white wheat. FP Genetics first acquired the licence for AAC Cirrus produced by AAFC breeder Richard Cuthbert’s Swift Current breeding program, said Wehrle. The variety, which will come to market this year, is high in protein and has very good baking attributes suitable for the bread market. FP Genetics then picked up BW402, also from Cuthbert’s program. Wehrle said the variety is suitable for the baking and noodle-making markets.

When AAC Whitehead came onto the market, FP Genetics was immediately interested. “It’s a total agronomic game changer,” said Wehrle. “Its yields are right up there with CWRS wheats.” Wehrle believes the world market for hard white wheat is quite large. Much of it is served by Australia, though availability has diminished as that country’s farm production has been affected by drought and wildfire. Quality attributes such as protein, gluten strength, extensibility and stability of the dough, will be the determining factors for success with millers, bakers and noodle processors, said Wehrle.

FP Genetics is now engaged in product tests with end-users for all three white wheats. Wehrle is clearly optimistic about the potential of CWHWS, but he’s also cautious. “There is less than 20,000 acres of production in Canada today, so it’s pretty small,” he said. “We need to be very, very careful we don’t overbuild this market on the front end until we have the demand from the end-users. If we have demand from end-users, we will have a business here for sure,” he added.

Getting farmers on board to grow the variety is the least of Wehrle’s concerns, though. Farmers, he said, will grow it if there’s demand, which is often followed by a pricing that is competitive with other crop options.

GROWING CWHWS

Lethbridge farmer Ryan Mercer of Mercer Seeds said he enjoyed growing CWHWS. It is similar to CWRS, agronomically speaking, but there is no risk of bleaching with CWHWS, he said. “You can get one rain event on a CWRS crop and you’re downgraded. Whereas with CWHWS you don’t have that.”

Early CWHWS varieties were prone to lodging and difficult to thresh, he said. Yield was also an issue. “I think he’s really onto something if he can increase the yield by that much,” he said, referring to Randhawa. “That would be a desirable thing for growers to grow, and then it would be a matter of developing the market.”

Nicole Rogers, founder and CEO of Agriprocity, has developed an agri-food trading model that focuses on longer-term, transparent and direct relationships between farmers and food processors. She helped Lomond area farmer Glenn Logan to container ship CWHWS wheat to an end-user in the Middle East. Rogers said buyers like CWHWS because it’s very functional, but not too expensive.

In underdeveloped markets, the navigation of delivery logistics can be a challenge. Rogers pointed to containerized shipping as a tangible and practical solution for farmers who want to direct export.

Functional logistics hubs do exist, she said, pointing to Manitoba as a good example. “All the containers come into the centre of Canada, and most of them leave empty,” she said.

Consumers are drawn to small-batch production and anything that makes the end product stand apart from its mainstream counterparts, such as GM-free or regenerative farming, said Rogers. “Consumers will pay a premium for boutique wheat,” she said. “It really comes down to a good marketing story.”

Like Rogers, Logan believes container shipping is the best option for farmers just getting into this class. Initially, it’s a good way to move product to a smaller volume market where the farmer has control over quality, he said. Once it becomes mainstream, bulk shipping appears to be a little more economical. “But the supply has got to be there,” he said. “If the supply is not there, the market will look elsewhere.”

Back when CWHWS was in its early days, Logan multiplied seed for two years, but sold very little and wound up using a lot of it in his own feedlot. “It doesn’t make any money when it’s in storage,” he said. “And elevator companies in Western Canada weren’t really inclined to tie up their space either, so there were few delivery opportunities, other than selling into the feed market.”

He admitted, though, that AAC Whitehead does sound promising. “I think farmers will be really attracted to the yield increase,” he said. “Twenty per cent is really substantial.”

“I’d grow it again if I thought I could sell it,” he said, adding he believes other farmers are open to new opportunities, too. “They’ll certainly take a look at it. If all the stars line up, they’ll buy into it,” he concluded. “But it will take a lot more effort this time to try to revive it.”

Comments