“IT’S NEVER LIKE THIS”

BY IAN DOIG . PHOTOS COURTESY OF ITALPASTA

Canada has seen a growing number of positive tests for COVID-19 among employees at meat processing facilities, which has resulted in slowdowns and closures. This has been most pronounced in Alberta where the Cargill plant in High River is to resume production May 4 following a two-week shutdown. In contrast, agri-food processors have fared much better. Just as seed plants, elevators and farm-to-export transportation links have weathered the pandemic remarkably well, grain-reliant food manufacturers have continued to function, even upping production to meet an aggressive surge in consumer demand.

Weathering the pandemic has perhaps been easier for non-meat food companies due to the way they are staffed and configured, but food manufacturers have leveraged this inherent protection.

“Protocols have been very effective in the milling industry,” said Gordon Harrison, president of the Canadian National Millers Association. As of April 27, he was aware of no illness-related production pauses at milling facilities. “The Canadian milling industry has enjoyed a high rate of operational continuity throughout the pandemic. It has been very fortunate.”

Flour mills are typically large facilities where maintaining physical distance between workers is relatively easy. “That basic fact was a starting point for looking at now how do we do even better at social distancing. What are the additional steps we can take to reduce person-to-person contact, exposure, etcetera?”

“The Canadian milling industry has enjoyed a high rate of operational continuity throughout the pandemic.”

This has allowed mills to flex their production muscle to meet increased retail demand. The country milled about 3.2 million tonnes of wheat in 2018, producing about 2.4 million tonnes of flour. The bulk of Canadian flour is sold domestically, and sales were flat for some years as consumers cycled through grain-dodging diets. Sales have begun a slow uptick in recent years, but the pandemic brought a sharp increase in demand for retail-sized packaged flour. As flour remains readily available to consumers, the size of flour packages produced by individual companies may have changed as they streamline operations.

“The milling companies in that retail flour business have been running very hard to meet the increased demand,” said Harrison. The initial panic purchasing of food staples has likely given way to increased home baking and food preparation as the population is subject to isolation. “I think by this point, consumers have realized there will be flour on shelves again and they don’t need to buy a two-year supply,” he added. As retail sales have perhaps modestly offset lost sales to restaurant and food service chains, major bakeries have remained operational, maintaining the flow of commercial baked goods into the retail and food service sectors.

According to Harrison, most of the nation’s millers are in part reliant on rail transport. While the supply chain made initial adjustments, millers have so far received grain without fail. Barring unforeseen surprises, the milling industry will continue to move product to market, he said.

Harrison also commends Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada for keeping food supply chain participants connected during the pandemic with efforts such as roundtable conference calls held three times a week.

The big question, he added, is will the upsurge in flour consumption and interest in home baking continue after the pandemic. Additionally, will consumers leave isolation with a greater appreciation for the dietary importance of wheat and oat-based foods as well as for the farmers, millers and bakers who produce them? Or, will the return to the normal operation of Canada’s food service businesses result in the decline of at-home use? Though he said there is no way to forecast, Harrison suspected the answer is somewhere in between, and per capita grain consumption may not change greatly post-COVID.

To keep up with a sharp increase in demand for pasta, Italpasta has streamlined its product line to six from 63 and hired additional employees.

Pasta demand has likewise increased during the pandemic. Over the three months prior to mid-April, sales of Italpasta products rose about 30 per cent said Joe Vitale, owner and president of the Brampton, ON business.

Producing packaged pasta products made from durum semolina grown in Saskatchewan and Manitoba, the company typically does $100 million in sales annually and employs 225 to 250 workers. Seventy per cent of its pasta is sold in Canada, with the balance predominantly exported to the United States.

Of Italpasta’s 55,700 square-metre (600,000 square-foot) production facility, two thirds is dedicated to warehousing products. This space is empty as the company races to keep up with demand. While producing up to just under 227,000 kilograms (500,000 pounds) of pasta daily, total orders amount to 454,000 kilograms (one million pounds) daily. “It’s never like this,” said Vitale. He is not sure it will be possible to catch up if sales continue to mount at the rate they have in recent weeks.

But it’s not for lack of trying. The company acted quickly to boost production and create contingency plans when panic buying set in. Returning to basics, production focused on just six pasta cuts of its usual 63. This now includes spaghetti, spaghettini, penne, fusilli, lasagne and elbows. While streamlining allowed greater and more efficient production, additional employees were hired. Automated systems and the size of the facility have made social distancing of the workforce convenient, and employees now wear masks and have their temperatures taken daily.

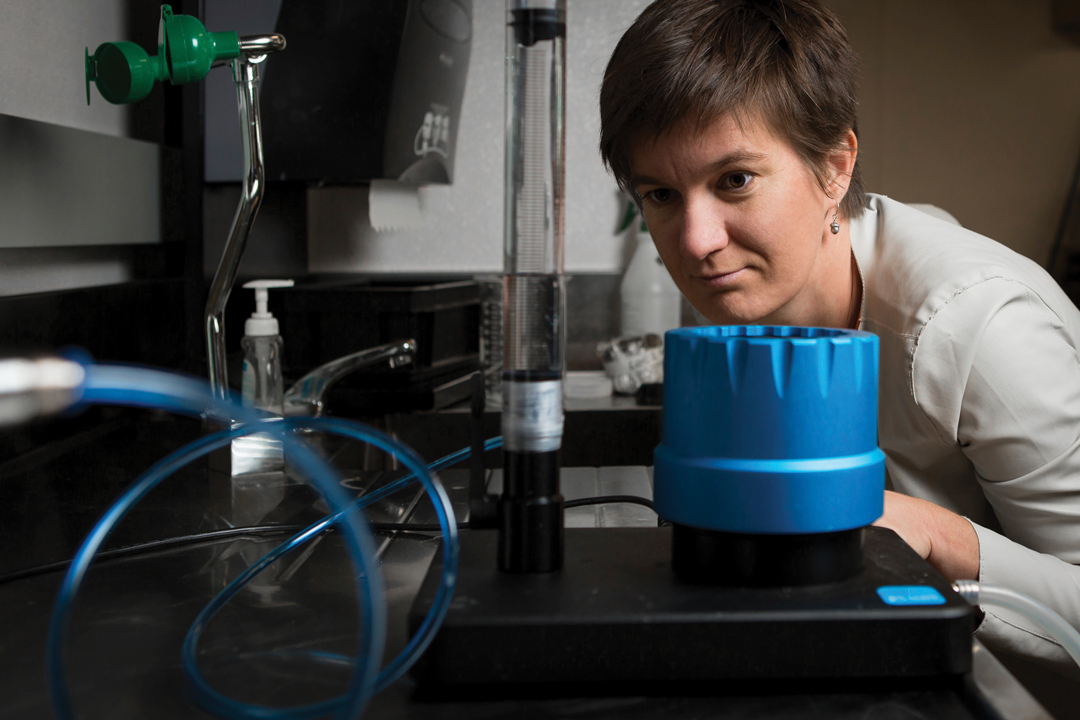

Italpasta owner and president Joe Vitale is confident the supply chain will continue to bring in the raw ingredients the business requires and to transport its finished products to market.

Though he said transport is “getting sticky,” the company has good relationships with multiple trucking companies and the large grocery chains such as Loblaws, Metro and Sobeys now conduct their own pickups. “We should be OK with the transportation chain,” said Vitale. “Between what we have and what the chain stores have, I think we’re very well protected.”

Confident distribution of Italpasta products will continue uninterrupted, Vitale is not worried about the company’s raw ingredient supply. Its central supplier, Howson and Howson is located outside nearby Goderich, ON, the location of grain-filled Lake Huron port elevators. “Believe me, the wheat is there,” he said.

While Vitale reassures consumers they need not worry about the availability of pasta, he echoes Harrison’s hope that the pandemic will heighten their appreciation of Canadian made food. “I’m not tooting my own horn, but with the best semolina in the world, Canadians produce the best pasta in the world.”

Comments