HANDS-ON TECHNOLOGY

BY TREVOR BACQUE • IMAGES COURTESY OF TISDALE’S AG SAMPLING SYSTEMS, STORM, NEXSOURCE

The digital side of farming is a huge source of technological development. While this special issue of GrainsWest naturally focuses in part on data, apps and devices, there is plenty of innovation happening on the mechanical side of farm technology, too. Here we examine three unique products being used by farmers to improve grain-related processes.

Grain sampling might be the world’s most inexact science. Kim Althouse, founder of Tisdale’s AG Sampling Systems, knows the busy lives of farmers is culprit No. 1 when it comes to inaccurate samples.

There are so many things going on at harvest time that sampling isn’t top of mind, said the Tisdale, SK, resident. “The guys hauling from the combine who are charged with collecting a sample may or may not know the scoop-and-pail sampling procedure or appreciate the importance of a representative sample in the marketing process.”

Gravity fed, the Sample Master dispenses a measured flow of grain into a five-gallon pail.

Having worked much of his career as a grain buyer and terminal manager, Althouse witnessed improper sampling techniques and human error on a regular basis. Once he was “retired,” he began developing a simple device that would produce a truly representative sample of an entire load of grain. He completed a conceptual design in January 2018, and by harvest, prototypes were in the hands of farmers.

The relatively low-tech device is available in three models, weighs about 2.3 kilograms and can be affixed to any swing-away auger with its universal adapter. The exoskeleton of the Sample Master is 3D printed with polylactic acid, allowing for rapid production. Eliminating a tedious task as well as the potential for human error, the device uses gravity to allow a measured flow of grain to move from inside the auger to a five-gallon pail outside the auger. Within the device, a hollow tube with an adjustable rotation speed measures the number of individual samples collected. An adjustable aperture into the tube can account for individual sample size and variability in the kernel size of various grains.

“Because marketing has become more and more important to farmers, they want to establish a brand that the buyer can believe in,” said Althouse. He added that his creation is never caught texting or otherwise ignoring the task at hand. “Farmers also want to be able to determine their own issues with quality, such as moisture and protein, and the value that comes with that.”

Larry Woolliams farms near Airdrie and tried the Sample Master for the first time last fall and was impressed with its simplicity and accuracy. “It’s getting a sample throughout that whole load, but if a person is standing there with a hockey stick, maybe they’ll get three samples at the start, and maybe not until the end,” he said. “It takes one thing off their plate while loading.”

With 9,000 acres under his management, dependable sampling is important for Woolliams—another reason the Sample Master is here to stay at his farm. “It’s easy to hook up. It literally takes two minutes,” he said.

The patent-pending device costs between $750 and $900, depending on models, but was a small price to pay for Woolliams come harvest. “The results were good,” he said. “It proved to be a nice fit for our operation. I love it.”

With STORM, seed goes from the seed source into the conveyer, to its treatment boot, or atomizing chamber, depending on model for application of treatment and conditioning and off through a polyflight mixer to the truck.

STORM SYSTEM

Many farmers make seed treatment part of their pre-seeding routine. And although most don’t like to see a storm at seeding, they may feel more comfortable with a STORM portable seed treater. The acronym stands for Seed Treatment Optimized Rate Metering.

The seed treater is for all farmers, but also an excellent choice for those working on a just-in-time schedule. “There’s no need for dirty bins or possible contaminated loads. You can treat and go right into the field,” said Leanne Marin, STORM product manager.

The treater comes in two sizes—the FX, suitable for most farmers and the PRO, typically preferred by commercial seed growers and retailers. The FX handles up to 1,800 pounds per minute while the PRO is capable of up to 2,800 pounds of seed in the same 60 seconds.

The main efficiency has been realized through a metered conveyor. The seed is metered directly from the source and the treater itself can handle crops as delicate as soybeans. The seed goes from the seed source into the unit’s conveyer to its treatment boot or atomizing chamber, depending on the model. Here, the treatment and conditioning is applied and the grain is off through a polyflight mixer to the truck.

Beyond that, a farmer can hook up two different chemical totes through peristaltic pumps, depending on the desired makeup of their seed coat. Also, a peristaltic pump system meters treatment by matching accurately, through a calibration process, to the seed being metered through the conveyer.

With his family, Ethan Klassen farms 9,500 acres in Alberta and Saskatchewan. The Coaldale seed grower used to have a USC model capable of treating about 500 pounds of seed per hour. He upgraded to the Storm FX this spring, more than tripling his hourly treatment capacity overnight.

“The way I had it figured—this treater versus the old one—I could spend an extra full week in the field instead of treating,” he said. “I have saved more time than I thought because of the cleanout, and calibration is so much quicker. That factored into the purchase—how much more efficient is it going to make me?” Klassen also noted his cleanout time has been greatly reduced, down from 90 minutes to between 30 and 45.

The STORM has an electronic interface into which farmers can pre-program seed treatment jobs. These can also be downloaded for transfer to a computer. As well, the interface lets farmers program, in batch size, exactly how much seed they want to treat. According to Marin, if a farmer is short a few thousand pounds, they can go back, punch in their exact needs and treat the seed with no waste.

Klassen, who produces many crops including soybeans said STORM’s conveyor system is gentle on seed.

“As the science behind farming progresses, so does seed treating,” said Marin. “You do what you know best until you know better and then you do that.”

Despite its typical use in the construction industry, flameless heaters have found homes on some Prairie farms. They are being used as a viable alternative to a stationary grain dryer.

HOT AND DRY

Jason Lenz farms in west-central Alberta near Bentley and, like many farmers, faced a wet, snowy harvest in 2016. He didn’t own a grain dryer and custom options were limited. So, he thought outside the box and rented a flameless heater.

Most commonly used to heat large buildings on construction sites, flameless heaters hook directly to grain bins and pipe air in at the desired temperature. Despite not being a traditional agricultural product, Lenz saw the machine’s utility and knew it could be used on his farm. “What makes this thing really work is that it’s zero per cent humidity,” he said. “That’s the hard part to believe.”

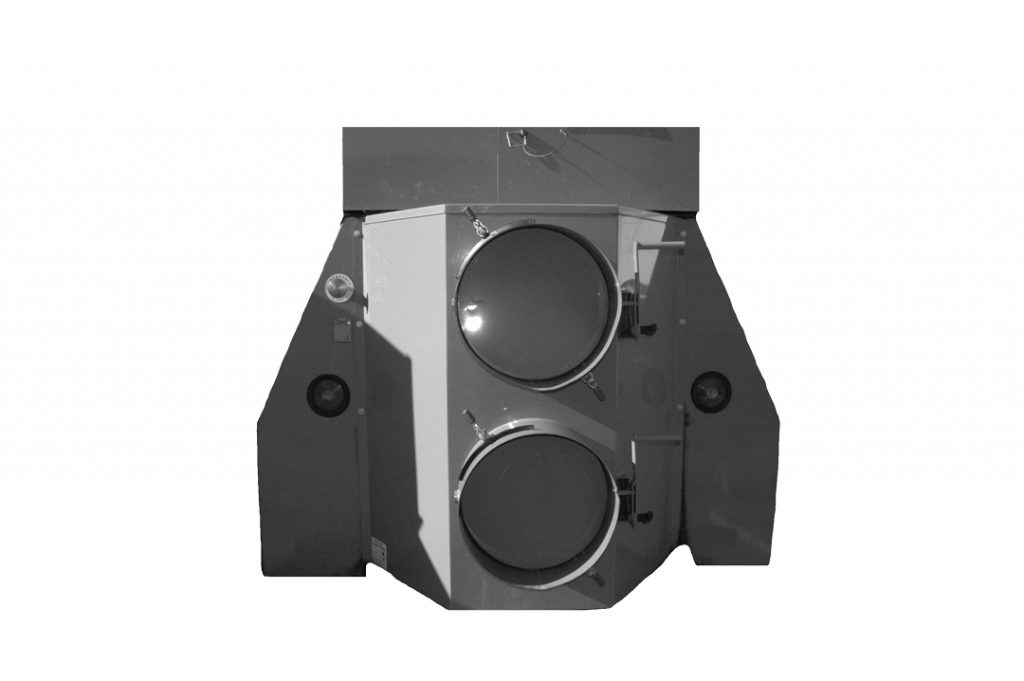

Using diesel power, the enclosed, single-axle tow-behind unit agitates hydraulic oil in a flameless, sparkless, low-pressure environment. The oil is cooled and circulated, not burned, providing a clean, pollution-free discharge to the target environment, according to Darcy Fraser, power and leasing manager of Nexsource in Sylvan Lake.

“It works the same as a normal grain dryer with fans blowing hot air, but it’s a drier heat,” he said. “Farmers were looking for alternatives to the standard grain dryer. We tried the flameless heater on quite a few farms. They were quite happy with how it was drying.”

Because of the unit’s portable nature, Lenz was able to drive it around his yard to any bin site and connect to two 16-inch ports that hook to large collapsible tubes. As the engine revs, the temperature can increase to more than 80 C. Bins need to have a hopper bottom or a side-mount fan to be compatible.

As the unit pulls in outside air, exhaust exits through a top pipe. Lenz believes this method is superior to natural air drying, where outside humidity in his area is sometimes as high as 60 per cent. He found his cereals dried quicker than he predicted, taking 5,000 bushels of wheat at 17 per cent down to 14.5 in 30 hours. He also discovered he was moving less grain around.

His overall bill to rent the unit for a month was $5,250 and it was an easy calculation once he looked at what he was drying. “On a 5,000-bushel bin of malt, all you have to do is dry one bin to keep it at malt quality to pay for that unit,” he said. He added the diesel is exempt from carbon taxation, which removes another cost of production on a unit he won’t necessarily need every year. “There are more and more guys using them all the time. For guys who don’t have an actual grain dryer setup, it’s a very viable option and cost efficient.”

Unlike typical grain drying units, a flameless heater doesn’t require a generator set to power it and is generally a considerably smaller financial investment. It may cost a farmer between $5,000 to $10,000 per month to run a flameless heater, whereas grain dryers are permanent structures that often start at $250,000.

A flameless heater setup, depending on BTU, may range from $75,000 to $110,000, Fraser noted. He added a heater would also have a healthy lifespan since it’s only used a few months out of each year. “With proper maintenance and care for the units, they should last a minimum of one to 15 years,” he said.

Comments