CARBON COMPROMISE

AGRICULTURE AND CLIMATE POLICY IN A SECOND-BEST WORLD

BY TAMARA LEIGH

The pressure is on for Canada’s federal and provincial governments to cut carbon emissions and demonstrate meaningful progress to reduce the impacts of climate change. In an ever-evolving environment of new policies and regulations, Western Canada’s grain growers are working to make sense of what the impacts will be when the dust settles and the bills come due.

“Agriculture is a success story on the whole issue of reducing carbon emissions,” said Kevin Auch, who farms near Carmangay, AB, and is chairman of the Alberta Wheat Commission (AWC). “Grain producers have already made strides in reducing the amount of energy we use and sequestering carbon in our soils. We are part of the solution.”

Over the past year, significant changes have been made to climate policies across the Prairies, all with different timelines and approaches to reducing carbon emissions. Agricultural organizations like AWC have invested their time in meeting with decision makers to make sure that agriculture is part of the discussion.

“One of the other things that governments need to recognize is a carbon tax will be reflected in costs to farmers—not just fuel, but other inputs and transportation of those inputs,” said Auch. “We want them to recognize that putting a tax on carbon shouldn’t disadvantage grain farmers. We rely on exports into international markets and can’t pass those costs on. The price of wheat is the price of wheat.”

Carbon pricing places a per-tonne fee on carbon emissions, sending signals to producers and consumers to reduce their consumption of fossil fuels by increasing the cost. In a cap-and-trade system, government caps the overall level of carbon pollution from industry, and assigns quotas to emissions-intensive industries. If a business exceeds its emissions limit, it can buy unused quotas, or carbon credits, from other companies.

According to Jennifer Winter, an assistant professor of economics and scientific director for the energy and environmental policy area at the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy, the outcomes of both mechanisms are the same—increased cost of production for carbon emitters.

“These policies work because they change incentives. The point is to make emissions-intensive goods more expensive, so a cap-and-trade system is going to make emissions-intensive goods more expensive in the same way a carbon tax will,” she said. “What you get with a cap-and-trade system is certainty about emissions reduction and uncertainty about price. A carbon tax gives you certainty about price and uncertainty in the amount of emissions reduction.

“It is also important to remember that greenhouse gas emissions don’t just come from fossil fuels, so carbon taxes or cap-and-trade systems are not necessarily a silver bullet in terms of fixing our emissions problem,” she added.

Climate policies often use a combination of market mechanisms, along with regulation, to deal with things that can’t be priced or are difficult to measure. Winter pointed to Alberta’s new climate policy, announced in November 2015, as a hybrid approach to emissions reduction.

ALBERTA’S NEW CLIMATE POLICY

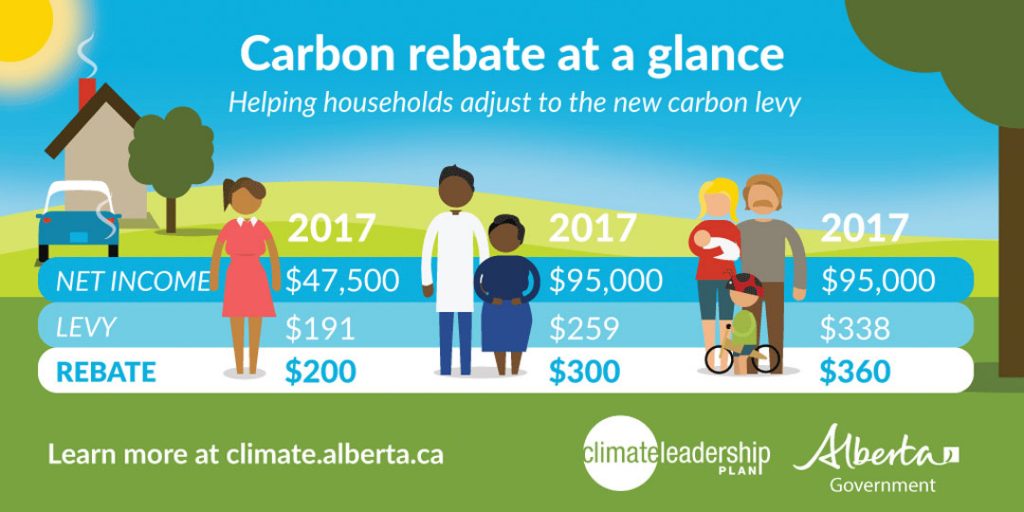

On Jan. 1, 2017, Alberta’s new carbon levy came into effect—applied to fuels at a rate of $20 per tonne. One year later, the levy will increase to $30 per tonne. It will be included in the price of all fuels that produce greenhouse gas emissions when combusted. These include transportation and heating fuels, such as diesel, gasoline, natural gas and propane. The plan also includes a cap of 100 million tonnes on greenhouse gas emissions from the province’s oilsands.

“The province is very concerned about the competitiveness of large emitters. They have provided a baseline for the oilsands industry, and they will issue credits to that industry,” Winter said. “If emissions intensity is above the baseline, then they will pay, but if they are below, they will have credits they can trade. It’s a merging of a carbon tax and cap-and-trade system.”

Alberta farmers play a role in that system through the carbon market that allows farmers to sell offset credits earned by using conservation cropping practices that increase carbon storage in soils and lower emissions from fuels and fertilizer. Since 2007, the voluntary management changes made by Alberta farmers have reduced greenhouse gas emissions by more than 11 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalents (Mt CO2e), representing a value of $150 million in carbon offsets.

The provincial government has also excluded farm fuel from the carbon tax. According to Alberta Agriculture and Forestry, an estimated 84 per cent of grain and oilseed producers’ energy costs are associated with diesel and gasoline. In addition to the exemption, many farmers will benefit from the small business tax cut and new funding for energy-efficiency programs and innovation.

On Oct. 24, 2016, the NDP announced a $10-million investment to strengthen programs that will help producers become more efficient and reduce consumption, emissions and costs. Overall, Alberta’s Climate Leadership Plan commits to a strategy that will see all revenue from the carbon tax—an estimated $2.5 billion—reinvested in measures to reduce pollution, including clean energy research, public transit and programs to help Albertans reduce their energy use.

LESSONS LEARNED FROM B.C.’s CARBON TAX

With growing apprehension among Prairie farmers, many are looking to British Columbia, where a carbon tax has been in place since 2008. Between 2008 and 2012, the price on carbon emissions increased from $10 per tonne to $30 per tonne.

“In the beginning, we took about a five per cent hit on fossil fuels,” said Rick Kantz, president of the B.C. Grain Producers Association, who farms near Fort St. John, B.C. “Since then, we have had the tax removed from our fuels. We still pay it on natural gas, so grain drying and activities like that get taxed.”

The greater impact for B.C. grain producers has come through increased costs passed on through shippers, including rail and commercial haulers, who help get the grain to market. Kantz is watching the situation in other provinces carefully because the decisions made in other parts of the country will impact one of B.C. farmers’ most important inputs—fertilizer.

“If other provinces put a price on fertilizer production, we’re going to be hit for sure,” said Kantz. “Most of our fertilizer is shipped in from out of B.C. An increase to fertilizer costs will be a bigger hit for us than our fuel, per acre.”

When the B.C. carbon tax was introduced, the BC Agriculture Council (BCAC) lobbied hard for exemptions, eventually getting a partial rebate on natural gas used in greenhouse production, and a partial reduction on marked gas and diesel. BCAC executive director Reg Ens rejects the commonly held belief that B.C. farmers are exempt from the carbon tax.

“The key thing on the carbon tax is that B.C. farmers support initiatives to reduce climate change. Our farmers are impacted by climate change more than any other group in society. We have a vested interest in making things better,” he said.

The BCAC fundamentally disagrees with the B.C. government’s claim that the carbon tax is revenue neutral. The organization claims that the carbon tax goes into general revenue, and has been used to lower income tax and fund some social programs. The BCAC would like to see a reinvestment strategy for revenue generated by the climate tax to support climate mitigation, adaptation, research and innovation that will help the industry adapt to climate change impacts and reduce emissions.

“A carbon tax is an input tax. Income tax is paid when you have a successful year. Input taxes can affect cash flow and make it more challenging because if farmers have a bad year, they still have to pay the tax,” said Ens.

PRESSURE FROM FEDS INCREASES UNCERTAINTY

In October 2016, the federal government raised the stakes for the provinces to deliver on their greenhouse gas emission reduction goals by announcing that a federal carbon price will be imposed on all provinces that do not already have a carbon price or cap-and- trade system in place by 2018.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced that carbon pricing should start at a minimum of $10 per tonne of carbon dioxide emissions in 2018, and be increased by $10 each year to $50 a tonne by 2022. While the announcement sent a clear message on federal priorities to the provinces, it only added to the uncertainty in the agriculture sector around climate policy.

Levi Wood is president of the Western Canadian Wheat Growers Association, and farms in Pense, SK. He said the federal announcement will be cause for concern until the specific deadlines are determined and shared.

“We’re concerned about the way the federal government has chosen to mandate a deadline and institute a tax. There’s still a lot of grey area in terms of how it will all come together,” he said. “Really, what we’re looking for in our business is some assurance that we are going to have a predictable regulatory environment.”

The Wheat Growers, along with many provincial ministers of environment, were surprised by the federal announcement. The association would have liked to see more consultation with agriculture groups, and is hopeful that there will be more communication going forward. Wood said that it was evident that understanding the impacts to agriculture was not a priority when a proposal to study the effects of a carbon tax on agriculture was voted down by the House of Commons Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food this past October.

Among the many considerations, Wood wonders where grain growers will find the new efficiencies required to meet emission reduction goals. “A lot of these changes make good management sense on our farm, and we have already implemented them—things like reduced tillage, investing in more efficient machinery and developing best practices for fertilizer use,” he said. “In Western Canada, farms are getting as efficient as they can be. We are way out ahead of the curve.”

CARBON POLICY FOR A SECOND-BEST WORLD

Peter Phillips is a political economist and Distinguished Professor at the University of Saskatchewan’s Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy. His work focuses on technology change in agriculture, and the increasing overlap between new technology and reducing the impacts of climate change.

“Canadian producers have one of the lightest footprints per unit of output of the many jurisdictions producing food for the export market,” he said. “Agriculture is really a science-based industry. They are heavily engaged in technological change and adapting new science to existing and new problems.”

He said a good carbon strategy consists of three mechanisms: pricing, cap-and-trade, and public investment in research and innovation.

“Carbon pricing can lead to distortions in the way we allocate our resources. Cap-and-trade is a little bit better, but we know that the market is underfunded. So we still need the third sector, an investment strategy model,” said Phillips. “This is just one more rationale for governments and industry to spend more on agricultural research. The returns on investment are high, the economy and society benefit, but the benefits diffuse too quickly for private investors to put up all the capital.”

Ultimately, Phillips said governments are faced with the challenge of designing carbon policy for a second-best world.

“In a first-best world, you figure out what the best mechanism is and you say we’re going with that, but that assumes everything is in equilibrium and we’re not. We’re in a second-best world, where everything is out of equilibrium, and at that point there’s a burden of proof in public policy that one should spend time and energy validating that the measure you are going to propose actually achieves the goal you are seeking. So far, the debate hasn’t got there.”

Comments