TESTS SATISFY NEED FOR SPEED

BY IAN DOIG • PHOTOS COURTESY OF CHARLES GEDDES

It’s a lengthy and involved process to identify herbicide-resistant (HR) weeds that pose a steadily growing threat to farm fields. With almost $500,000 in funding provided by Results Driven Agriculture Research, a project is now underway at the Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) Lethbridge Research and Development Centre to simplify the procedure with the creation of rapid tests.

Research scientist Charles Geddes leads a team that includes Martin LaForest who studies herbicide resistance in Eastern Canada. Launched in April 2021, the project will wrap in March 2025. The samples being used to develop the genetic tests are supplied by the AAFC Prairie HR weed survey initiative. Geddes also leads this project, which samples 800 fields across the Prairie provinces every four years.

Whereas the survey assesses the status and impact of HR weeds, this project determines the mechanisms that confer herbicide resistance at a molecular level. The researchers use these mechanisms to develop genetic tests farmers can use to rapidly identify the type of herbicide resistance that may occur in their fields.

The latest Prairie-wide survey conducted between 2014 and 2017 estimated HR weeds cost farmers across the region $530 million a year. The 2017 Alberta Weed Survey estimated the annual cost of herbicide resistance to the province’s farmers at about $196 million. Per acre, this is about $17 on average.

“Herbicide resistance is a growing issue, and it continues to increase,” said Geddes. “We continue to find new types of herbicide resistance almost every year. The area in which we have resistant weed issues is also increasing.” The 2019 to 2023 Prairie survey results are not yet published, but the data indicates the economic hit to farmers has increased by 30 per cent over five years, he added.

For years, farmers and agronomists have relied on plant bioassays to identify suspected HR weed samples with the help of Prairie diagnostic labs. In the field, the uncontrolled weed must be allowed to mature so its seed can be collected. The lab sows the seed in a controlled environment, sprays it with the herbicide in question and compares the plant’s response to that of known resistant and susceptible populations. Samples are typically submitted in the fall, and farmers receive results sometime over the winter. Hopefully, this occurs in time to formulate a response for the coming season.

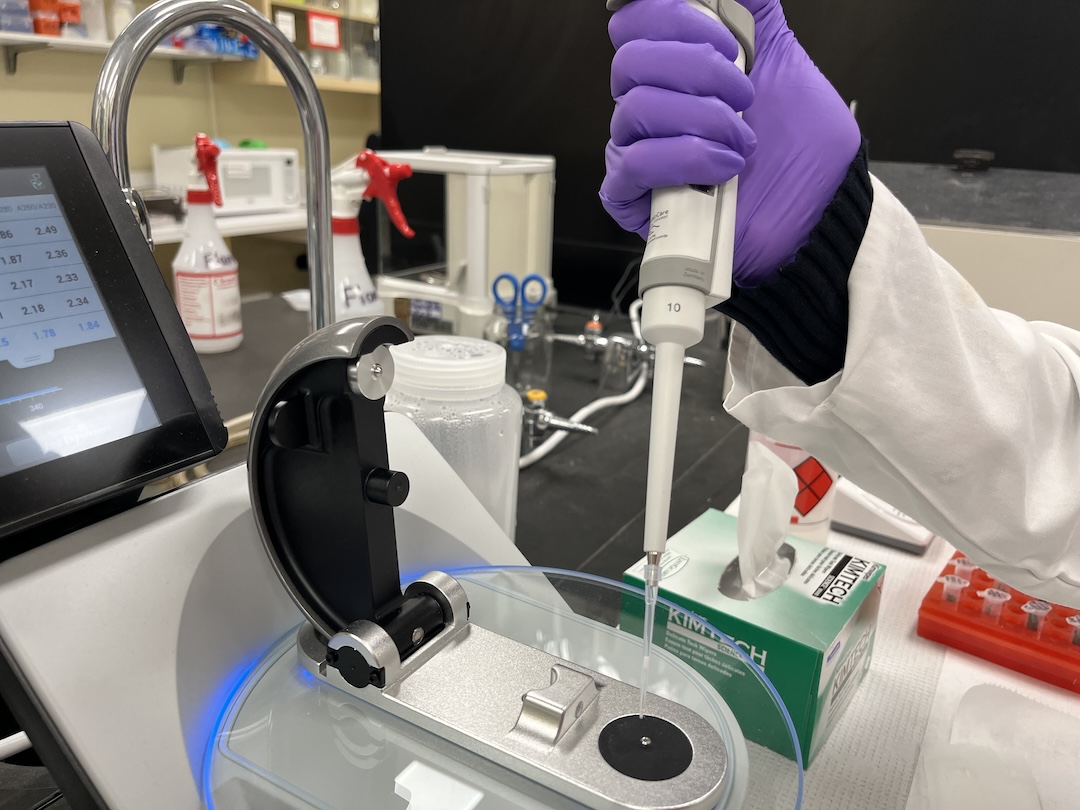

“Genetic testing offers the ability to diagnose herbicide resistance rapidly,” said Geddes. When a young weed is sprayed but not controlled, a sample of leaf tissue is collected with a sampling kit and submitted to a lab. The lab extracts DNA from the plant tissue (pictured above) to identify mutations that confer resistance. “It’s a less involved process that can provide a result back within about one to two weeks. A farmer can collect that leaf tissue early during the growing season, submit it and get a result back in that same growing season when they can still make some sort of a corrective management practice.”

He noted one limitation to genetic testing. To develop a test, researchers must first identify the mechanism that confers resistance in a weed. This must be discovered through the more involved bioassay process followed by molecular diagnostics.

Geddes’s counterpart, LaForest has had considerable success in the creation of rapid genetic tests that have been adopted as a service to farmers in Eastern Canada. “We’re taking a similar approach, but specifically targeted at the Canadian Prairies and weed issues that farmers are dealing with here,” said Geddes.

The project target was to develop eight tests over four years with each to focus on a weed species and a herbicide mode of action. The project has so far developed and validated 14 such tests. “Ultimately, these tests would be licensed to diagnostic labs that would offer this as a service to farmers,” said Geddes. “We’re trying to add another tool to the toolbox that will help farmers identify resistance early so they can manage it appropriately.”

Comments