SMOKE SHOW

BY ZOLTAN VARADI • PHOTO COURTESY OF UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI

Findings from a recent University of Missouri (MU) study seem to suggest farmers visit the seasoning aisle of their local grocery store for an unexpected remedy to crop stress.

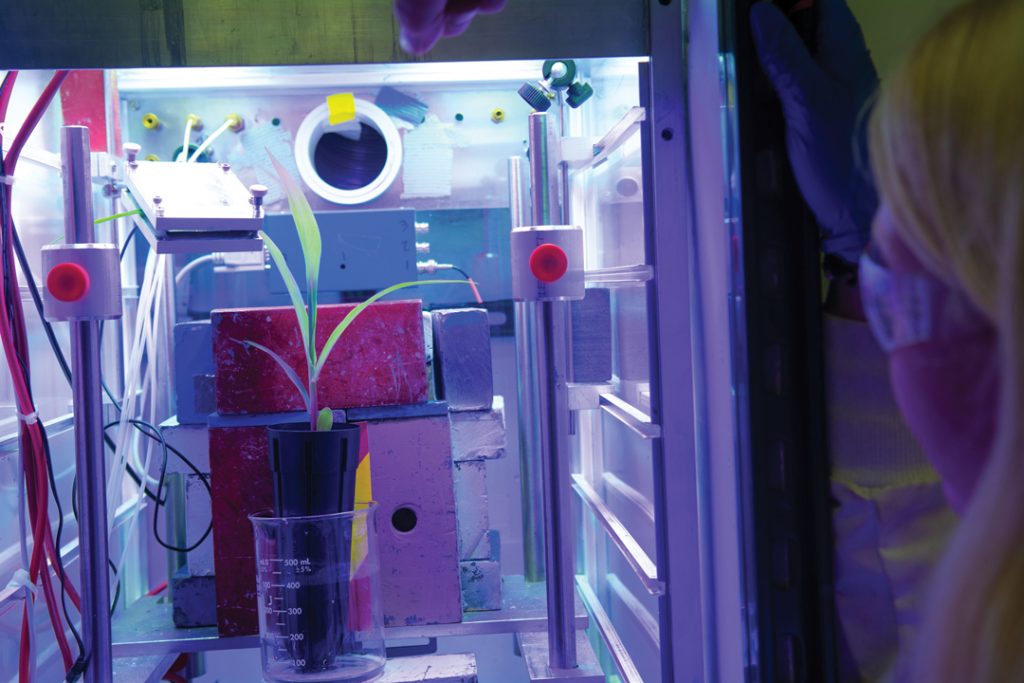

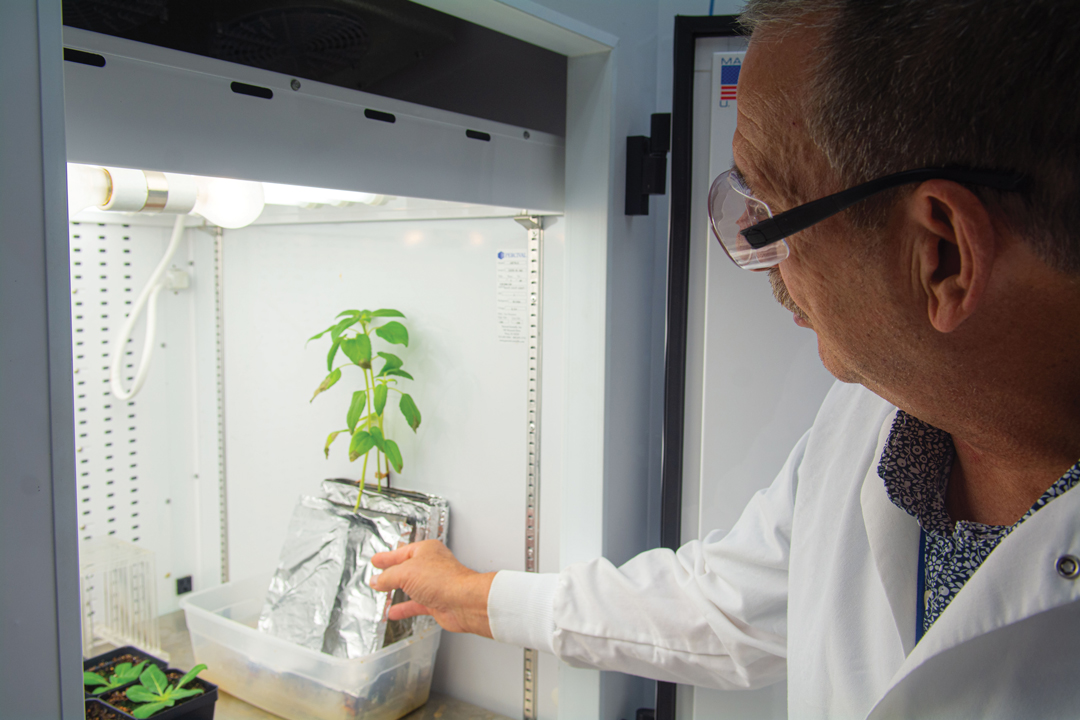

Spurred by the increased intensity of seasonal wildfires across the globe, MU Department of Chemistry research professor Richard Ferrieri and his team set out to study the long-term effects of smoke on plant growth. Inadvertently, they discovered the commercial cooking product they used to simulate smoke in the lab had a startling, positive impact on plants.

Ferrieri jokingly noted scientists are “not allowed to start a fire in the lab.” His team treated test plants with liquid smoke as a substitute for the real thing. Typically used to flavour meats, pyroligneous acid is produced by burning hardwood and plant biomass. Cold air is used to condense the smoke and produce the reddish-brown liquid.

The initial study grew sunflowers in soil treated with diluted liquid smoke. The researchers then administered carbon dioxide, which the plants converted to sugars. To track the movement of these sugars through the plant’s vascular system, they utilized radiographic imaging equipment at the University’s Research Reactor.

Surprisingly, the plants grown in the treated soil had partitioning within their vascular structure diminished. “The sunflower, as a dicot, has evolved vascular sectoriality,” said Ferrieri. “In the simplest terms, the left-hand side is not connected to the right-hand side. From an evolutionary perspective, plants have probably evolved with this sort of architecture to meter out resources to their specific parts in a strategic way, especially when attacked by insects or pathogens. Plants have evolved the ability to deal locally with these little problem areas. If a caterpillar is chewing on one leaf, then only that one part of the plant will respond.”

As with exposure to wildfire smoke, crops increasingly face broad environmental stresses more so than localized threats such as having individual leaves nibbled. With the pyroligneous acid cuing the plant to react across its entire body rather than in a localized way, this may benefit its growth performance, said Ferrieri.

Further research by Ferrieri’s team seems to bear this out. In the second stage of the study, they grew two cohorts of sunflowers. Half were treated weekly with liquid smoke, half were not. The treated plants had greener, thicker, lesion-free leaves, thicker stems and twice as many flowers. They also contained 35 per cent more lignin, a key structural material found in plant support tissues.

“Smoke treatment not only altered the physiology of the plant in terms of its ability to move its sugar resources throughout the plant, it changed leaf biochemistry to make thicker, less disease prone leaf tissue with this lignin content,” said Ferrieri. “What started as a study to look at post-wildfire smoke has now moved into looking at this as a biostimulant.”

While further study is needed to fully understand this phenomenon, ag industry players have already responded to the study’s findings. A California company is burning almond shells to produce a soil amendment product similar to liquid smoke, and in China, pyroligneous acids are being used on cabbage and cotton crops.

But, before grain farmers purchase liquid smoke by the pallet, note that the benefits of liquid smoke-treated soil appear to be limited to crops such as sunflowers, soybeans and canola. There is no evidence the treatment works on crops such as corn, wheat and barley, said Ferrieri.

Comments