FIGHT AGAINST PLANT DISEASE EXPANDS

BY TAMARA LEIGH • PHOTO COURTESY OF MARIA CONSTANZA FLIETAS

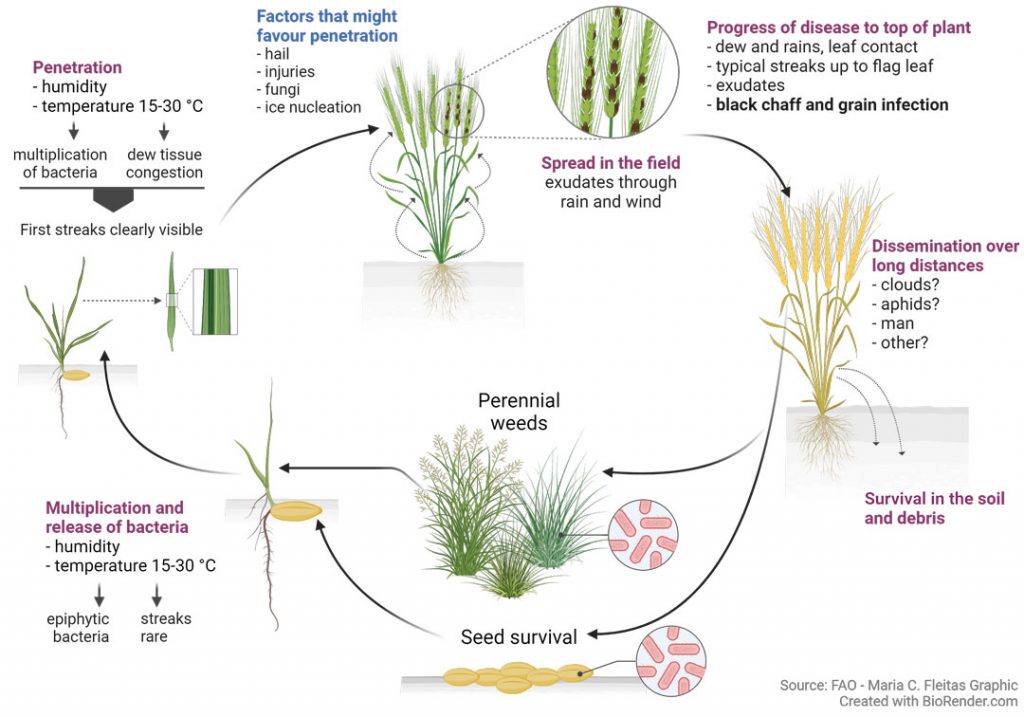

Bacterial leaf streak (BLS) is a subtle intruder, but given the right conditions, it can cause significant yield loss and affect future crops in wheat and barley. Most commonly transmitted through contaminated seed, the disease has the cereal industry pushing on all fronts to break the chain of transmission, starting with the development of an effective seed test to help farmers manage the risk and prevent it from spreading.

Jeremy Boychyn is the Alberta Wheat and Barley Commissions’ agronomy research extension specialist. He first encountered BLS last summer. While attending industry events, southern Alberta farmers presented him with samples.

“I was presented with plant material and asked what I thought it was. Two different samples were brought to me, and it didn’t look like a common fungal pathogen, it looked like leaf burn or something environmental,” said Boychyn. “The first sample I thought may have been impacted by hot weather. When the second sample came along, the symptoms were evident through the entire leaf area and looked like it impacted yield because it had taken away from the flag leaf, so I started to ask questions.”

Boychyn turned to Michael Harding, crop assurance lead with Alberta Agriculture and Forestry. Given his time in the field and as a research scientist in Brooks, Harding has more experience than most with bacterial leaf streak.

“This is something that has been around for a long time, but it’s usually just a curiosity that shows up every once in a while and doesn’t do a lot of damage. Over the last 10 years that has been changing,” said Harding.

In 2018, his team started seeing more outbreaks in fields around southern and central Alberta. Working with Jie Feng at the Alberta Plant Health Lab, they gathered infected tissue samples, isolated bacteria from the plant leaf and sent them to AAFC bacteriologist and taxonomist James Tambong, who identified the pathogen as Xanthimonus translusens pv. undulosa. Preliminary trials to determine if there were any obvious differences in cultivar tolerance or resistance found that the pathogen was virulent on all major varieties of red spring wheat, barley, durum and winter wheat.

HARD TO DIAGNOSE, RARELY APPEARS ALONE

“It’s easy to misdiagnose BLS because it usually doesn’t just occur in isolation. There are often other fungal diseases that can sometimes make it challenging to know whether BLS is present and in a lot of cases BLS is present with other fungal diseases as well,” said Maria Constanza Fleitas, a post-doctoral fellow working on BLS at the University of Saskatchewan.

In the early stages of BLS, pale streaks run parallel to the veins of the leaf. These lesions will darken and take on a water-soaked appearance as the disease starts to develop. Under humid conditions, infected areas ooze bacteria seen as yellow thread-like masses that dry into thin shiny scales. Eventually the lesions grow together to cover large areas of the leaf, turning chlorotic (yellowing) and then the tissue becomes necrotic (dark and dead looking) and finally dies. At this stage, the disease can look very similar to Septoria leaf blotch or tan spot.

Damage to the leaf reduces the photosynthetic leaf area of the plant, resulting in poor grain filling and reduced yield. Some farms have reported up to 40 per cent crop loss as a result of BLS.

The weather is the biggest influence on the prevalence of BLS in a given year. The bacteria thrive in warm, wet conditions, spreading over short distances through water splash and as plants rub against each other. Large storm systems and wind can carry infected material between fields and into new areas where it can become established if it finds a susceptible host.

“You need the pathogen, a susceptible host and the right weather conditions,” said Fleitas. “If you don’t have all three you won’t get the disease; the triangle of the disease has to come together.”

Fleitas is working with Randy Kutcher on a project funded by the SaskBarley Development Commission to develop a seed testing protocol to detect pathogenic Xanthimonus translusens on barley seed. The protocol uses colorimetric reaction, a visual detection method that can detect kernels infected with pathogenic X. translucens that cause disease on cereals from those that cause disease on non-cereal hosts.

Also underway is a project to develop a method to test seedlings and adult plants in the greenhouse or growth cabinet. It is intended to screen commercial cultivars and other germplasm for sources of resistance that breeding programs can use to develop resistant genotypes.

They are also working with Harding and other agronomists across the Prairies to determine BLS prevalence and virulence of X. translucens strains isolated from barley samples across Western Canada. This information will indicate the extent of the problem to pathologists, agronomists, breeders and farmers as well as other stakeholders in the cereals value chain.

“Right now, scouting and detailed record keeping are the best tools we have to manage BLS,” said Harding. “If you see it, reach out to the people that can help you, like me or your regional seed lab or provincial plant health lab. You don’t want to be using grain from heavily affected fields as a source of seed in 2022, or you’ll be headed for catastrophe. Hopefully, by next season we can have seed lots tested.”

Several seed labs are also responding to demand for a seed test. “The prime prevention and key to controlling BLS is going to be seed testing to make sure the seed is free of BLS to avoid bringing it into your field,” said Rachael Melanka, client success manager with 20/20 Seed Labs. “It will also let growers know if their field is at risk for BLS infection and make a decision about whether to use that seed or source new seed. If everything goes well, we expect to have a seed test available next season.”

To assist farmers prior to a seed test being made available, 20/20 Seed Labs is promoting a leaf tissue test. “Since there’s no in-crop management, we can confirm BLS on leaf tissue for you,” said Melenka. She added, farmers or agronomists can pick 10 symptomatic leaves, wrap them in a paper towel, put them in a Ziploc bag and drop them off or mail them to the lab. “Our disease diagnosticians can confirm if it’s BLS or if we’re seeing something different. It’s all about collecting the most information to set you up for success.”

While farmers need to be aware of BLS and incorporate monitoring and controls into their operations, much work is being done to get ahead of disease before it establishes itself more broadly across the Prairies. If managed right, BLS could remain a relatively rare occurrence.

“We don’t want to be taking a disease and continuing it through generations. If we can stop the disease in the field where it is and not propagate infected plants, we can reduce the spread,” said Boychyn.

Comments