PROGRAMMING POWER

FROM DIGITAL GAMES TO AUTONOMOUS TRACTORS

BY ELLEN COTTEE

You can call Brian Tischler many things—an innovator, a programmer, a farmer—but don’t call him a techie. Despite eschewing the title, He is the creator of AgOpenGPS, a cutting-edge, free, open-source code used to automate farm vehicles. With users all over North America and even a few in Europe, the project Tischler started as a way to make his own farm more efficient has grown more than he could have expected.

GrainsWest: How did you get involved in automated farm technology?

Brian Tischler: I kind of have two lives. I started out in electronics, specifically in biomedical electronics in a hospital—all those things that go beep and keep people alive. I did that for quite a few years before I took over my dad’s farm in the ’90s.

GW: Your farm is a bit different than others in Alberta. How do you operate it?

BT: Together with a neighbour, we farm about 2,500 acres. We also work with a rancher. Our farm is a mixed collaborative farm. We’re all independent, but we work together and get the benefits and the win-win of both cattle and grain farming. It allows us to grow more crops and have a built-in market for our crops [since we can use them as feed for the cattle] and straw. It works out really well.

GW: Did you think you’d ever get back into programming while running the farm?

BT: Along the way, I’ve still done some programming and electronics work. It’s something like riding a bicycle—you never forget it. When I first got to the farm, I got into game programming. Of course, it had no real-life purpose for the farm, so I gave it up for about 10 years. Then we needed our tractor and our air seeder to be able to map where we went in the cab, so I started looking into GPS and using my game background and experience and just started programming it. That became AgOpenGPS.

GW: How would you describe AgOpenGPS?

BT: AgOpenGPS is just a Windows tablet or laptop application that reads the GPS data from any GPS receiver and does auto-steer, section control and mapping—all the functions of many of the commercial products that you buy and put into your tractor. In a nutshell, that’s it. It’s a precision-ag application for remote controlling the tractor and its implements. It shows where you’ve been and turns off the tool that’s doing the applying [of fertilizer and seed] where you’ve already applied—that’s called section control. It’s crazy, because a lot of farmers in Europe are much more interested in it than here in North America.

GW: Why do you think that is?

BT: In European nations, they have smaller fields, so the cost of a $10,000 to $15,000 piece of equipment [like a new tractor with automated controls] is just not justified.

GW: Is this a complicated program

to run?

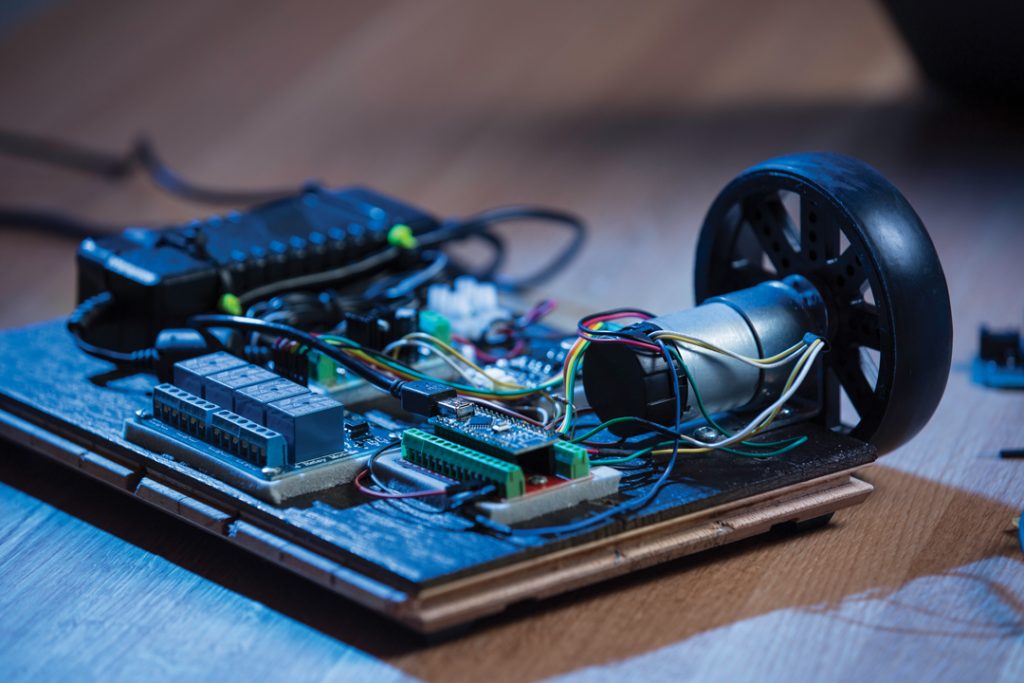

BT: This is totally do-it-yourself, but we—and when I say we, I mean me—haven’t completely de-geeked it yet. You have to buy a few little parts like a circuit board, USB adapter, antenna and basic transmitter—do some wiring and soldering. You do have to know a little bit of electronics.

GW: There’s a large community around AgOpenGPS. Do you know how many people are using it?

BT: There’s no download counter, so I have no idea. The software is stored on GitHub, and all you know is when people comment or fork it, which is when they download it and make their own version. There are plenty of people who have done that, and the licensing is such that if you download AgOpenGPS and you make changes, all you have to do is make sure the source code is available. That’s the entire limitation—if you improve it, share it.

GW: How interested are farmers in automation?

BT: There are a lot of processes—seeding, combining, some of these more complex operations we do on the farm—it’s going to be a long road to automate those. The auto industry has had the technology for 15 or 20 years, but it’s just starting to be put out. They’re at the point where simple routes can be programmed and run, but fully autonomous cars are not there.

Second, when we talk about autonomous vehicles, we have to ask, “What is an autonomous vehicle?” A little radio-controlled car is driverless, but there’s still someone holding a remote control. The Society of Automotive Engineers has broken it down into levels of autonomy. When we talk autosteer, like cruise control in your car, that’s one level. It’s operating your gas pedal. You don’t have to do anything. Second-level means the piece of equipment can steer itself. Then you get into third-level, where it can turn around and do some basic functions.

The top level is where the vehicle is like a hired man—you just tell it, “Go out there, start at the yard here, go harrow that quarter of land and come home again.” Autonomous doesn’t mean driverless or these space-age things without a cab. It’s all about a) how safe it is and b) when does the autonomy stop making sense.

GW: In terms of that assessment, how far do you think farmers would be willing to take autonomy?

BT: It comes down to how comfortable we are with something going wrong. Like with an air seeder, there’s a lot going on with that. It’s extremely important to make sure it seeds properly, with enough seed in the right spots. With today’s technology, it’s too complicated. We can’t discount how specialized and skilled the farmer sitting in the seat is.

It’s like cars. If you’re just going to be driving down a road, that’s one thing. But if you’re going to put a travel trailer behind that car, and then a boat behind that trailer, now with all three items you’re going to back down a boat launch and put the boat in the water, it takes tremendous skill—but you’re still just driving a car.

GW: Are there any problems, aside from eliminating man-hours of labour, that automated farm technology can solve?

BT: Herbicide resistance is a big one. With the high number of herbicide-resistant weeds, and no new major herbicides coming out lately, we’re going to need a weed solution. Robotic weeders, I think, are going to be a major step forward in this type of technology, hands down. It’s going to be a machine that goes out there and picks weeds, burns them, lasers them. It’s not a time-sensitive thing. It can go out there 24 hours a day and weed a crop, it takes no intervention on the human’s part. I think that’s the big tech coming forward—ways of getting around herbicide resistance and tending crops.

GW: What do you see as the future of AgOpenGPS?

BT: This whole thing really needs a repository, a place for source code and ideas. I’m hoping a university could do this. Students can take it on as a project to build this “home” for all things ag—farmers helping farmers. You can post stuff on forums, but then how do you find it? That’s the big challenge. A way to catalogue these ideas is something that’s really needed for this movement to grow.

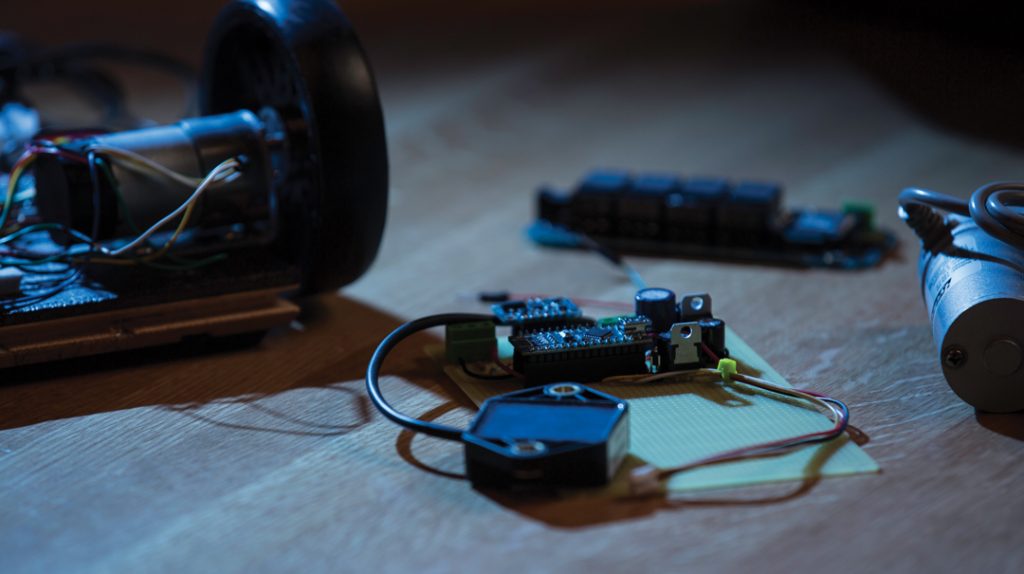

Automated farm machinery controls may include an Arduino Atmel microcontroller (top), which determines the roll and pitch of the vehicle, an automated-steering simulator (middle) for program testing and a linear actuator (bottom) to operate clutches, levers, throttles and gates.

Comments