FARM TO FORK GOES DIGITAL

HOW BLOCKCHAIN WILL REVOLUTIONIZE AGRICULTURE TO THE BENEFIT OF FARMERS AND CONSUMERS

BY TREVOR BACQUE

Bitcoin took the world by storm about two years ago and has since risen, fallen, crashed, burned, re-risen and may be soaring or bottoming out on the stock market as you read this. When the world’s biggest bubble comes along, it’s hard not to take notice, and Bitcoin news certainly is enthralling. However, what has captured the attention of many is the technology behind Bitcoin: blockchain.

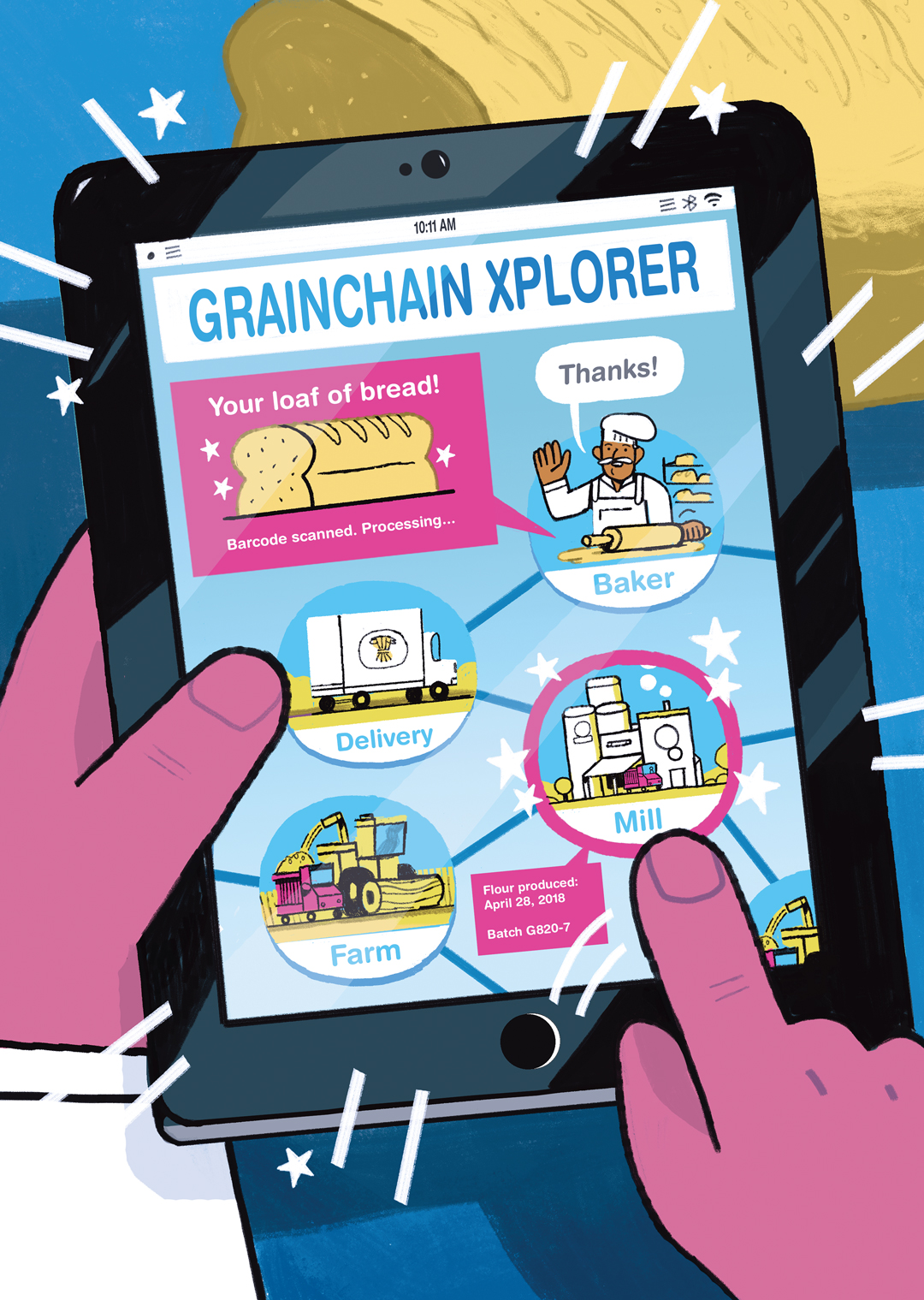

Simply put, blockchain is an immutable and unchangeable public ledger, or record, of transactions. All dealings are recorded in the public eye for all to see. It tracks something, usually cryptocurrency, going from A to B to C and so on. However, its application is not strictly limited to digitized dollars. The agribusiness world certainly thinks there is potential for blockchain to reduce administrative burden, increase traceability and provide consumers with confidence and peace of mind at the grocery store like never before.

And it’s already happening.

Between November and December 2017, worldwide commodity trader Louis Dreyfus Company sent a load of U.S. soybeans to China utilizing blockchain technology. What unfolded was a success. Many players were involved, including three banks and the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The outcome was the same as with regular shipments—soybeans went to China. The main difference was the transaction’s back-end process, which received top marks from Louis Dreyfus’s perspective.

“The results of this transaction clearly demonstrated the advantages of blockchain. There were significant efficiency improvements for all parties involved,” said Robert Serpollet, the company’s global head of trade operations. “It cut out much of the unnecessary, non-value-adding work and eliminated duplicate tasks. It cut the time spent on email exchanges, rekeying, sending and signing documents or identifying discrepancies. And, thanks to the platform’s automatic function, the conditions of the smart contract were automatically filled.”

Although Louis Dreyfus has only conducted the single trip using blockchain, it doesn’t appear to be a one-off publicity stunt. “The technology has evolved quickly, and this could lead to production later this year,” said Serpollet. “But there is still a lot to be figured out, including the choice of technology, level of adoption, legal framework and other issues. This will not happen overnight.”

Louis Dreyfus has a sterling 100 per cent success rate with blockchain to date, and oil and energy industries are also on board with the technology, according to Elaine Kub, author of Mastering the Grain Markets: How Profits Are Really Made, adding that the food realm is long overdue for a disruption. “The agricultural commodity shipping supply chain is one system that’s still reliant on paperwork,” she said. “That’s inefficient. This is a very ripe target for change and efficiency.”

For Kub, the reduction in paperwork and the presumed reduction in human error due to blockchain’s unchanging nature has her excited for the future. “It’s a shared ledger, it’s not susceptible to tampering. The speed of it is where these grain companies are seeing this as an advantage,” she said.

Louis Dreyfus’s maiden blockchain voyage cut document-processing time fivefold, and the company was able to monitor the operation’s progress in real time. Kub isn’t surprised to hear of these positive results because, unlike Bitcoin’s lengthy verification period, the commodity world operates in a “seconds” timeframe. “It’s worth spending the money because of the speed and reliability of it,” she said.

HARDWARE

David Yee is the VP of Saskatchewan operations at the Prairie Agricultural Machinery Institute, based in Humboldt, SK. The growing digitization of agribusiness clued him into blockchain.

“There’s something interesting happening in farming. Many of the stages of output or activity, those things can be converted into a digital packet,” said Yee. Information within the supply chain could be placed into these digital packets, making it all instantly accessible.

To that end, Yee’s group has been helping people conceptualize how the farm-to-fork movement may go digital, particularly on the hardware side via sensors. The group is promoting the possibilities of this technological innovation to agricultural commissions and informing farmers about it while generating their interest.

These palm-sized sensors would be the conduits to track commodities from A to Z. For instance, a farmer loads a crop from his or her grain truck into the bin, where a sensor is dropped in. Then, it is transported to a country elevator, and the sensor stays with the grain as it’s deposited. As the grain is then loaded into a CN or CP railcar, the sensor continues to go with the grain. The train then heads to the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority where it is loaded onto an ocean vessel—sensor included—before heading into international waters. All the while, each transaction is logged and verified through a blockchain.

By the time the crop gets to China, all the digital paperwork is complete, all transactions are verified to be true, and it can be physically verified that the device remained with the load throughout its journey by truck, train and boat. “They sift out the sensor [in China], and they are happy,” said Yee.

The technology will someday start at the farm level, according to Yee, affording Prairie farmers new-found control and instant information, such as enhanced tracking, traceability and verification, all for a fraction of what it costs now. This inherently transparent tracking tool has the capacity to make the transportation of food highly secure, giving farmers valuable oversight in marketing their crops and securing public trust in the agricultural sector and farmers themselves.

“These particular sensors can help them with their conditioning and storage for drying,” he said. “As blockchain becomes prevalent—this virtual sort of transactional paradigm—it will make it move faster. It will overcome borders and hopefully has the capability to overcome trade barriers. Everyone in the third-party logistics chain [food shippers, wholesalers and retailers] could ultimately benefit from this. The consumers feel very, very satisfied with the chain of custody in the food supply chain.”

By marketing it correctly, Yee said blockchain could leverage brand-new opportunities for all types of farmers through digital technology and a trusted supply chain. For those marketing specialty crops that are in high demand and have specific, verifiable growing characteristics, the prospect of higher profit is even greater.

By 2023, Yee expects blockchain systems to come online and start jockeying for position in the great blockchain race. “I think this is something that can beat autonomous farming,” he said, suggesting that this technological innovation could see widespread implementation long before the similarly revolutionary mainstreaming of self-driving farm machinery takes place.

FARMER FOCUS

If farmers are the ones who stand to gain the most, then count Cole Siegle as one happy dirt scratcher. The Fairview farmer manages 1,000 acres of canola and wheat annually. Supply chain issues can be difficult for many farmers, including Siegle, a crop technology graduate of Lakeland College. He keeps track of all he does on his farm through electronic management tools, leading him to believe there should be a little more moola at the end of the day for his digital fidelity.

“I should be able to extract a premium for keeping my records up to date with blockchain,” he said. “I am excited to see if this technology will bring on-farm traceability.”

Siegle believes consumers fascinated by food production would be the ones most pleased to be able to scan a product at a grocery store and know that it’s local, how it was produced or the distance it travelled to their kitchen.

“Blockchain has a way of connecting the whole supply chain, which is huge. That will reflect positively on the farmer,” he said.

BIG-BOX BLOCKCHAIN

A hallmark of new technology is that it may stick around longer than a fortnight and have widespread industry uptake (sorry, HD DVDs and MiniDisc players). It appears blockchain may have sticking power. IBM is currently collaborating with 10 of the world’s largest food retailers and producers to pinpoint sources of food contamination using blockchain.

IBM’s goal isn’t to simply swap out an existing system with a new one, but rather to achieve three ideals, according to Manav Gupta, IBM Canada’s chief technology officer of cloud technology. Blockchain should be used to reduce food waste, provide better food-industry visibility—from consumers to retailers to regulators—and create greater confidence in the provenance of food. This last point would help ensure the organic flax you buy is actually so, and that its origin, food miles, safeness and authenticity are guaranteed.

He said that the widespread use of blockchain will reduce food waste since it allows a specific product to be traced at any time. It would allow contaminated products to be traced quickly, while safe food would not be unnecessarily disposed of. Ultimately, it would push for a global food system that would better serve consumers than ever before in human history.

Gupta’s practical example of food-borne illnesses underscores blockchain’s utility. If one grocery chain has a food recall on cabbage, all retailers throw out their cabbage just to be safe, he said. Now, through blockchain, the time it takes to trace food contamination and outbreak sources is being dramatically reduced and food is being saved.

“That’s immediate visibility and being able to track where it came from. As well, on the consumer side, we’ll be able to test health and nutritional claims. Some of these claims are in the blockchain itself and become immutable,” said Gupta. “Details about the food handlers, certifications they have … these are all pieces of data that consumers and supply chain people view as critical information.”

Today, the changes are being driven equally by consumers and industry, according to Gupta. “We are more interested in finding out how much our food has travelled. Is this salmon really wild salmon, or is it farmed salmon, for example? The consumer is getting more aware and wants more information about food and the carbon footprint,” he said. “Industry is focusing on providing better visibility—one, to each other; two, to the regulators; and three, nobody likes bad headlines when there is a food-borne illness getting traced.”

IBM is working with the Hyperledger Project, an open-source project intended to make blockchain available to anyone, whether they’re selling eggs in the countryside, clothing en masse or anything in between.

And just like Yee, Gupta sees how Canada’s farmers can earn more through the power of blockchain. “Early adopters will certainly have tremendous benefits of the first-mover advantage,” he said. “Some commodities are at a premium, and for those commodities in certain parts of the world, being able to trace that right down to the farm it came from, like those in Canada, with its pristine soil and lack of environmental damage—that commands a premium dollar.”

Above all, blockchain will continue to be adopted by a growing number of companies. That is the biggest reason why this technology will revolutionize the world in a similar fashion to the internet. “Technology has to be no more expensive than what it takes to do that process today, or if it is, it has to provide an exponential benefit that outweighs the [cost],” he said, adding that when it comes to blockchain, the benefit is clear and the price is right. “They’ll do it by verifying and validating transactions in a near-costless manner. We’re only seeing the tip of the iceberg of the technology at this point.”

Comments