To TILL or NOT to TILL

Direct seeding is a custom fit for each farm

by Lee Hart

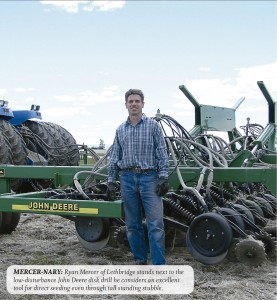

Alberta farmers Ryan Mercer and James

Jackson farm about 650 kilometers apart under vastly different growing conditions. Yet for the past 20 years or more, both have been committed to the concept of conservation farming.

Mercer’s family farm stepped into a direct seeding system with a Victory Seed-O-Vator in 1989, and although equipment and technology has changed, their grain and oilseed operation south of Lethbridge hasn’t been tilled since.

Jackson, who runs a grain and oilseed operation at Jarvie, about 150 kilometres north of Edmonton, said a total one-pass direct seeding system is a good concept, but that in his part of the world, he has produced the best results by harrowing to manage crop residue, along with one field operation just to blacken the seed row.

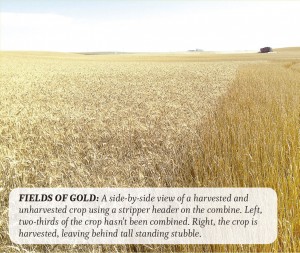

Mercer harvests crops with combines equipped with stripper headers, leaving stubble as tall as possible and undisturbed, making for easier seeding with a disk-type air seeding system the next spring. Meanwhile, Jackson gets the best distribution he can of often-heavy crop residue with rotary combines, but follows that with one harrow pass in the fall to better distribute chaff and straw. He also makes a pass with knife banding equipment in the fall, to apply fertilizer and blacken the seed row, before seeding directly overtop of that fertilizer band with a disk-type air seeding system the following spring.

Despite different conditions and approaches, both farmers have the same objectives: to protect soil from wind and water erosion, to improve soil organic matter and soil tilth, and to create a better environment for seedlings so they get the best start every spring. And of course, one of the underlying objectives for both producers is to make some money—sound economics is important.

The evolution of conservation farming

Prairie cropping practices have changed dramatically over the past 25 to 30 years. When conservation farming and direct seeding was first introduced between the late 1970s and early 1980s, some early adopters talked about first trying the technique on the “back 40” at night, so conventional neighbours wouldn’t see the craziness of seeding without tillage. But times have changed.

Statistics Canada reports almost a complete reversal over the past 20 years. In 1991, 69 per cent of all Canadian farmers applied conventional tillage practices, with only about seven per cent practicing no-till and about 24 per cent applying conservation tillage measures. In 2011, Statistics Canada reported 56 per cent of farmers were practicing no-till, 24 per cent used conservation farming techniques and only 20 per cent continued with conventional tillage.

Conservation farming is in a fine-tuning period, according to Rob Dunn, an agriculture land management specialist with Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development.

“I think most producers today are looking for ways to take the ‘disturbance’ out of the system,” said Dunn. “There will always be a certain percentage of farmers who, for a variety of reasons, will continue to practise conventional tillage. But certainly over the past 20 years or more we have seen the majority of producers move from conventional tillage to reduced tillage, to direct seeding with minimum tillage, to direct seeding with no tillage, and now many with disk-type openers have systems with ultra-low disturbance.”

But each farm and each region is different, said Dunn. Many dryland farmers in southern Alberta are committed to zero-till direct seeding systems, whereas in central and northern parts of the province that see more rainfall, cooler temperatures and heavier crop residues, it is still common to see limited field operations to manage residue and blacken the soil.

“Years ago, with conventional tillage, the main concern was the huge losses due to wind and water erosion of the soil.”

– Ryan Mercer

“Farmers dealing with heavy crop residue are looking at direct seeding practices, and standing back and looking for the best way to manage this residue,” said Dunn. “Can they manage this residue with a direct seeding system? Or … do they incorporate a very specific tillage operation that manages residue, and perhaps blackens the soil a bit to improve seed germination and growth?”

Depending on the growing season, heavy crop residue isn’t always an issue on his dryland farm. However, as soil organic matter has improved with direct seeding, and with very low disturbance improving moisture conservation, even in dry years managing crop residue is still important.

Mercer used a Flexi-Coil 5000 air seeding system for several years before switching to John Deere 1895 disk drills with mid-row banders about 10 years ago.

He has since moved onto using combines equipped with stripper headers since 2007, Mercer said he has found a better way to manage residue and still get optimum performance from an ultra-low-disturbance direct seeding system. The stripper header has fingers that comb up through the crop and clip only the seed heads into the combine. Depending on the year and crop, it isn’t uncommon for Mercer to leave 16 inches or more of standing stubble after harvest.

“Years ago, with conventional tillage, the main concern was the huge losses

due to wind and water erosion of the

soil,” said Mercer. “Fortunately, as farmers have moved into reduced tillage and direct seeding systems, we have moved beyond that.”

His main focus now is to improve soil quality with more organic matter, and improve moisture conservation.

“We’ve been at this for more than 20 years and we are seeing improvements in the soil,” he said. “Soil organic matter has increased from two to four per cent. The soil has improved tilth. Water infiltration rates have improved. Even in wet years we aren’t seeing as many sloughs. And in dry years we are seeing improved moisture reserves to carry the crop through.”

The 16- to 20-inch-tall crop stubble helps to trap snow, which adds to soil moisture reserves as snow melts.

Mercer said with healthy soil, proper crop rotation and active soil micro-organisms, crop residue is quickly incorporated back into the soil. And he was amazed at how tall stubble creates a warm microclimate close to the ground. Even with strong southern Alberta winds, it is warmer at the base of the stubble, and wind doesn’t impact crop seedlings.

Northwest of Edmonton, Tom McMillan of Pickardville, AB, has also become a fan of stripper headers to help manage crop residue on his direct seeding operation. He ran a conventional-tillage grain and oilseed operation for many years that usually involved three tillage passes in the fall, two more passes in the spring before seeding, as well as harrowing.

“We began direct seeding in 2001, so we are relatively late bloomers,” he said.

Westlock County ran a direct seeding demonstration on his farm for a number of years and, watching those results, he saw the system worked.

“We saw poorer soil began to improve, and overall there was no yield penalty and it was a lot less work,” said McMillan.

For the first few years he just had to work to keep the knives sharp in the straw chopper to get the best distribution of crop residue as possible. But then he found a better way to manage the residue. In 2013, he outfitted the combine with a stripper header. Depending on the setting, the stripper header combs up through the crop, for the most part, removing only the seed head, leaving the stubble standing. Even in an area with plenty of moisture during the growing season, he said it is no problem for his John Deere 1895 disk drill to work through tall standing stubble.

Even though he’s in the same, sometimes-cooler, north-central part of the province as Mercer, the tall stubble creates a warmer microclimate close to the soil, so McMillan doesn’t worry about blackening the seed row to improve seedling vigour.

He added that it’s important with any cropping system, but particularly with no-till direct seeding, to follow a proper crop rotation that includes grains, oilseeds, pulse crops and legumes. It is beneficial not only for crop production, but also helps in managing residue.

Jackson, who grows wheat, canola and pulse crops, isn’t alone in his practice of blackening the soil so it warms faster and improves crop growth. He still wants the ground protected by stubble and residue, but said there are many -2°C mornings right after seeding when that dark band of soil warms up quickly, helping young canola plants overcome the cold.

Controlled traffic farming

Jackson is one of only a handful of Alberta producers taking his conservation farming practices a step further, and adopting controlled traffic farming (CTF). This system of limiting all traffic over a field to specific and permanent wheel tracks, or tramlines, was developed in Australia, then pioneered in Alberta by south-central-Alberta farmer and crop consultant Steve Larocque.

Jackson has been involved in a provincewide CTF study for the past three years. He readied equipment in 2011 for the first year of the project involving about 430 acres. Recognizing the benefits he applied the concept to more of his farm. In 2013 with larger seeding equipment he applied CTF to about 80 per cent of his land, and plans to expand that to 95 per cent of his acres in 2014. Along with adapting “hardware” to CTF, the setup also requires time for management and field planning to optimize the system.

One of the main advantages of CTF is to reduce all equipment traffic over crop land, reducing soil compaction. This, in turn, should improve crop production, said Larocque, who farms at Morrin, east of Three Hills.

“Statistics show that perhaps 60 to 70 per cent of farmers are practising conservation farming and direct seeding technology.

– Peter Gamache

“Most years, wheel traffic over fields—even with reduced tillage or direct seeding—can cover as much as 50 per cent of your land,” said Larocque. “That all contributes to compaction. It can affect root development of crops, crop access to nutrients, and the movement of moisture through the soil profile.”

Larocque has been impressed with 110-bushels-per-acre yields on CPS wheat, and barley yields in the 120- to 135-bushels-per-acre range. He expects even more as soil conditions and management improve.

The first challenge is getting all equipment set for CTF. Both Larocque and Jackson, for example, use equipment that is either 30 or 60 feet wide. Wheels on equipment are set on 10-foot centres, and travel on set tramlines that are each about 20 inches wide. All field traffic must travel on these permanent tramlines, and operators need an accurate GPS to keep all equipment properly aligned with the tracks.

It’s with such accuracy that Jackson can make one pass to band fertilizer in the fall, and then directly seed over the fertilizer band the following spring. Depending on his preferences, he has the option to seed the following crop the next year directly into the same stubble row, or adjust the spacing on the drill and seed between rows.

While the traffic is limited, that doesn’t limit the way the land

is farmed. Larocque follows a zero-till, direct seeding system on his farm.

“It takes some time to get it set up, but each year, as you keep the traffic limited to these tramlines, you begin to see benefits in crop production, as well as your overall operation,” he said.

As the ground mellows, plant roots have improved access to moisture and nutrients, which translates into improved yields. Larocque said the tramlines have allowed him to be on fields two to three days earlier, which is especially important at seeding, but is a benefit for all field operations. The firm tracks of the tramlines can carry equipment, and with reduced soil compaction water infiltrates through the soil faster. Not only are the tramlines solid running tracks, but improved water infiltration through the soil allows fields to dry out sooner in the spring or after a rain. He can travel faster for all field operations, harvest efficiency is improved, and he’s already seeing fuel savings of five to 10 per cent.

Larocque said CTF is doing more to improve overall yields and field operations than any deep tillage operation that could be applied to fracture compaction layers—and CTF doesn’t require an extra $65,000 to $100,000 in specialized equipment. Larocque, who is a firm believer in minimizing field traffic to correct soil compaction, said one of the most important tools for direct seeding operations is a proper straw chopper that does a good job of residue management and distribution.

Controlled traffic farming is just some of the “fine tuning” producers are exploring to get the most out of their conservation farming practices, said Peter Gamache, a longtime soil conservation specialist based in Edmonton. He said limited tillage operations may play a role in specific situations, but he is a bit concerned when local farmers show interest in high-disturbance European tillage tools. They might have fit in across the pond, but may be a step backwards for western Canadian soils prone to wind and water erosion.

“Statistics show that perhaps 60 to 70 per cent of farmers are practising conservation farming and direct seeding technology. More are now starting to think about soil health and soil quality,” said Gamache. “Sometimes direct seeding may be blamed for a particular production problem, but, as some researchers have pointed out, one of the most important tools of farming is to follow a diversified crop rotation.”

Direct seeding and zero-till farming were initially used to reduce soil losses due to wind and water erosion, then farmers realized this system was also a very cost-effective way to farm—saving many field operations both time and money.

Comments