STAYING POWER

BY TREVOR BACQUE • ILLUSTRATIONS BY DOMINIC BUGATTO

Farmers are skilled at many tasks. Marketing an entire season of crops while in line at Tim Hortons or properly sampling a super-B of grain while scrolling social media are but two examples. One thing many farmers just aren’t too good at, though, is retirement. For so many, 65 really is just a number. With the wisdom they’ve acquired in the art and science of farming, they can continue to make a difference. And given the standard auto features and air-rider comfort of new-model tractors, the work has become more physically accommodating for senior farmers.

Famously reluctant to call it a day, many farmers are happy to change roles within their farm. By age 65, many have transitioned, in part or in full, away from the role of boss. New roles may include advisor, gopher, machine operator and shop worker.

At the Canadian Agricultural Human Resource Council (CAHRC) in Ottawa, ON, staff regularly monitor vital farmer data, including age. The group’s 2023 farmer survey indicates the average age of a Canadian farmer is 58. “If that’s your average age, you know there’s a number that are over the age of 65,” said executive director Jennifer Wright. She points out, though, that farmer is more than a job description. It can define a person’s identity. “It is who they are, and if they’re healthy and they’ve been a farmer all their life, they don’t feel they need to retire. There is also some undertone that, for the larger farms especially, there may not be enough help.”

Certain farmers may continue to work if they have no heir apparent, child or otherwise, to take over. This has become more common. Farm families are smaller than in generations past. From this diminished pool of potential farmers, many choose to work outside agriculture or within the industry but in other job categories.

Of CAHRC survey interviewees who identified as farm workers, 21 per cent, or 438 out of 2,119, were over 65. CAHRC believes the industry can collectively lower the average age of farmers and alleviate pressure on farm owners. To do so, it can recruit vigorously outside of agriculture and maintain or expand rural infrastructure to attract and retain workforces.

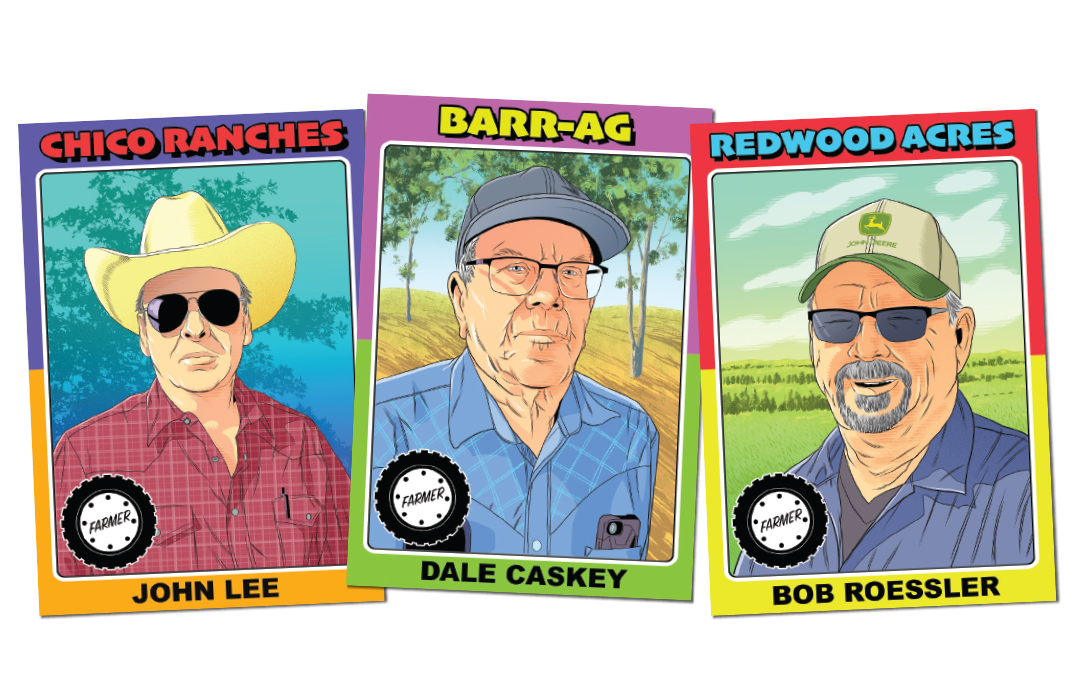

To understand why certain farmers carry on, GrainsWest interviewed a trio of Alberta farmers about their farming life before, and after, 65.

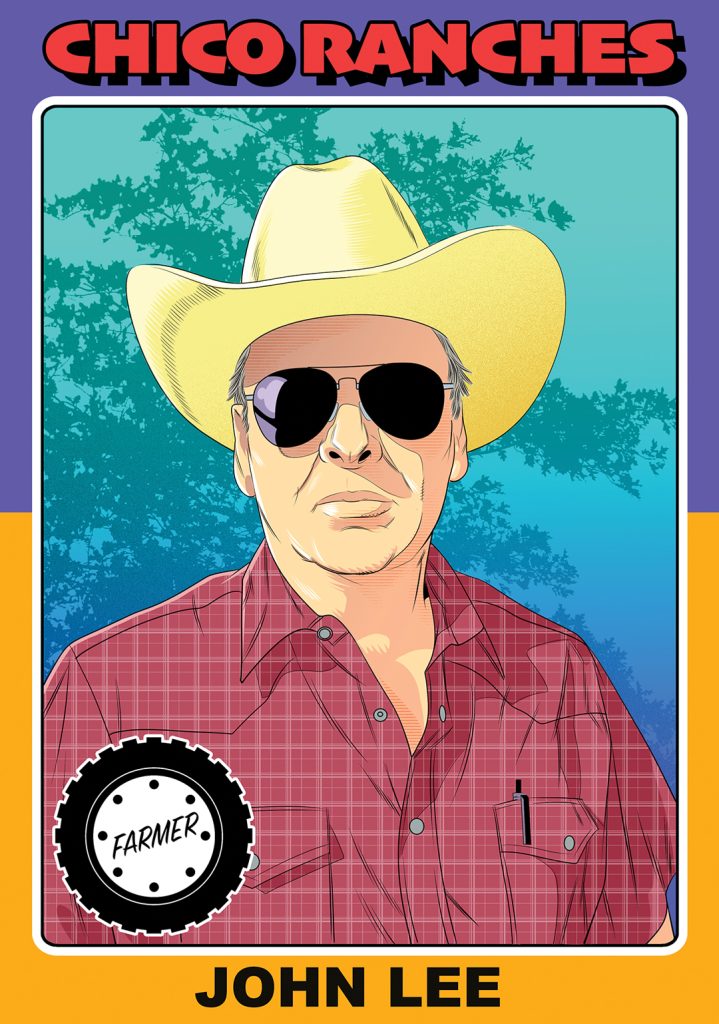

JOHN LEE, CHICO RANCHES

At his small mixed ranch northwest of Airdrie John Lee loves to spend time in the open field with his purebred Angus cows. The farm itself was not handed down to Lee. Quite the opposite. Born in the Fraser Valley on his family’s purebred Holstein farm, he left at age 18 to pursue engineering studies at BCIT. His first job was in design, product research and sales for a farm automation equipment distributor. Sent to Alberta to kickstart sales and help establish a dealer network for his company, he found the job very stimulating and fell in love with the province immediately. “Just the whole mentality of rural life in Alberta was so much better than what we were seeing in B.C. at the time for agriculture, politics and opportunity wise,” he said.

At Bittern Lake, Lee soon bought a mixed farm in 1973 in partnership with his sister Louise and brother-in-law Jim Lewis. They then bought an adjoining farm, combined the two and dubbed the operation Chico Ranches. They established and managed a purebred cow-calf herd as well as grain and hay production. Lewis was an American who grew up in the Angus business, which became a strong focus for the three.

In the early ’80s, the farm came into its own but suffered overland flooding across more than 11 quarters. Not believing this was natural, they approached the Alberta government. The government initially said the flooding was normal and denied water had been intentionally drained from nearby Hay Lakes into Bittern, which has no natural outlet. It later admitted this was not so.

The three fought the government for five years but eventually had enough. In 1986 they sold the property. In 1988 Lee, wife Jan and family relocated Chico Ranches to its present site near Airdrie. He now owns and operates a quarter-section and rents out substantial pastureland.

Through much of his farm career, Lee also worked at UFA as a corporate manager in various departments and retired at 58 to spend all his time at the ranch. His age neither stops him nor slows him down.

His son Taylor, wife Shannon and their two children live on the ranch, but neither of Lee’s adult kids want to fully take over the ranch. It’s just as well, because Lee estimates it couldn’t support an additional family at its current size. His kids’ duties increase as he gets older but because they work full-time in other industries Lee handles most day-to-day responsibilities. “This has always been a family operation since 1973, but, along with input from the family, I’m still the decision maker,” he said.

The size of the cow herd has fluctuated over the years. From 200 head, down to five, up to 100, now at about 50, Lee selectively focuses on private treaty sales and some consignment.

As agricultural technology continues to develop at a frenetic pace, Lee has embraced such innovation wholeheartedly. It has enabled him to continue to do what he loves.

He has a warm calving barn where mother cows can take shelter during February and March. Cameras installed throughout the barn and outside pens allow Lee to monitor the animals from the comfort of his house while minimally disturbing them. “If I had to get up and put clothes on at two o’clock in the morning and go out in -20 or -40 and do my three-hour check all night, I don’t think I’d be able to do that anymore,”

he said.

Another monumentally helpful innovation has been his round baler and processor. “The ability to put up good quality hay with less labour and then take that through to the feeding of it; one person is able to process that hay or green feed and bed those cows with considerable ease and not a lot of physical labour,” he said.

His morning and afternoon tasks present a laundry list of work each day. “One of the things I kind of kid about with people is when you cut back your cattle numbers and are what I call semi-retired, all of a sudden you become chore boy,” he said with a laugh. Family and friends are quick to pick up the slack when he needs help or requires a break.

Lee’s many off-ranch responsibilities have included stints as a director with 4-H Alberta, Alberta Angus Association and various provincial ag societies. One of his biggest accomplishments, he chaired the committee to establish the horse care code of conduct for the World Professional Chuckwagon Association in 2013. Two years later, his commitment to the sport earned him the organization’s highest honour, chuckwagon person of the year. “I was proud of that, it was significant,” he said.

Not having the wherewithal of his 25-year-old self, Lee simply believes more is more. “I’ve got aches and pains and a bad back,” he said. “If you’re involved with the rest of the family in decision-making and bringing forth ideas, you’ve got your mind working. That’s important. Physically, you need a reason to get up in the morning and certainly with cattle and livestock, it’s a necessity to get out there and check those calves or whatever it be.”

Nine years past the official age of retirement, Lee sees no sunset on his farm career, and that’s the way he likes it. Plus, there’s more to learn, even at 74. “I still have enjoyment with the cattle and the people in the business,” he said. “I always say this breeding of livestock is not an exact science and you continue to challenge yourself to make your cattle better.

“Retirement for a rancher or farmer would be to sell your agriculture assets and move off the farm or ranch, and I don’t see that happening. Maybe one day health will dictate that, but even if it does, maybe we just transition to something different here on the property.”

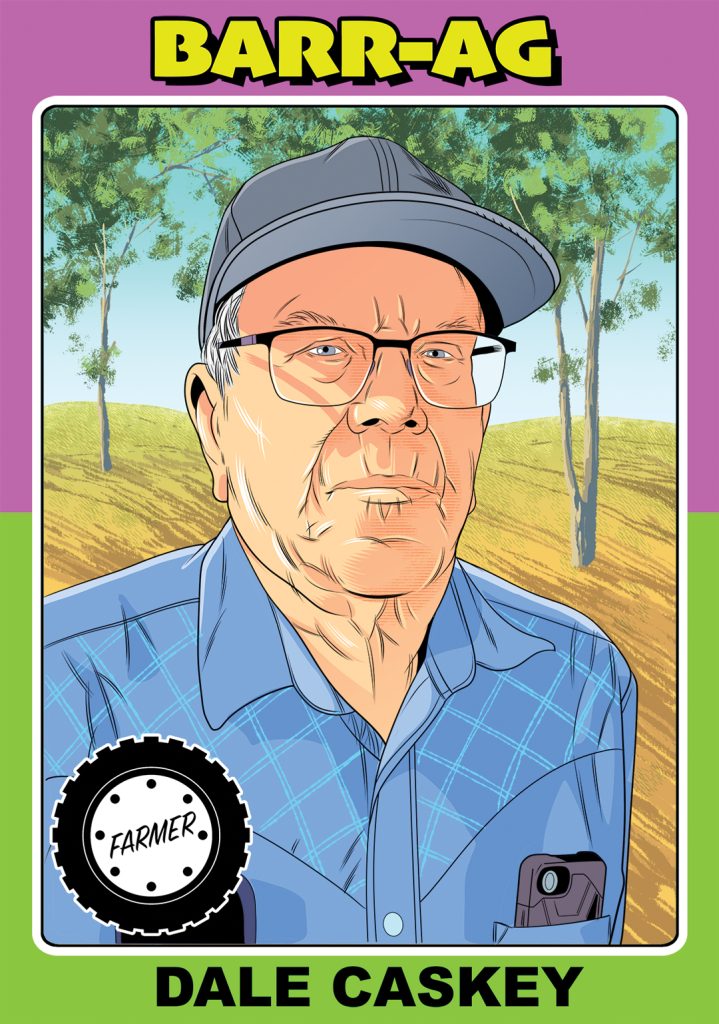

DALE CASKEY, BARR-AG

With seven decades of work in agriculture, Dale Caskey just can’t get enough. Recently, he has chosen to slow down a step or two, but he hasn’t quite figured out how to truly retire. At 81, he can still be found at the shop or office at Barr-Ag, a hay export farm and business a stone’s throw from his house in Olds. He has worked for Barry Schmitt, the company’s owner, for more than three decades across multiple businesses.

Born and raised on a mixed farm near Cereal, Caskey did childhood chores alongside his three brothers. As a young man, he bought a farm of his own 10 minutes up the road near Chinook with his wife Betty and three kids. While he operated the farm, he also worked lots of years in custom spraying. As Caskey pointed out, working as a custom spray operator in the ’70s and ’80s was quite different than it is today.

“There weren’t a lot of custom operators out there at the time,” he said. “Of course, all our equipment was not with the high-tech GPS of today or anything else. You sort of sprayed by seat of your pants.”

The family relocated to the Olds area in 1989. The sheep farm they bought was a brief experiment. “You buy them high and you sell them low, so that didn’t last very long,” said Caskey.

Looking for work in the winter of 1990, Caskey stopped in at a nearby hay plant where he met Schmitt. He enjoyed the entrepreneurial spirit and enthusiasm of his Saskatchewan-born boss. “He’s a hard-working man, an honest man and very easy to work with,” said Caskey.

A famous Barr-Ag story concerns Caskey’s first day on the job. As the lore goes, he began simply as a broom pusher and gopher. However, throughout the day, two separate pieces of machinery broke, both of which he fixed. By the end of day one he was plant supervisor.

Over the years, Caskey has watched Schmitt’s five children grow from infants to seeing a few become successors in the family’s hay export business. To Caskey’s liking, these were busy years during which he helped operate the farm and hay plant. During a few summers, he also helped manage the irrigation system at the Siksika First Nation.

Sixteen years clear of age 65, retirement still hasn’t crossed his mind. Up until last year, he oversaw dispatching of trucks at Barr-Ag, something he’d done for almost a decade. “I enjoyed working for Barry so much because it wasn’t a boring job, it was a challenge,” he said. “I never even thought about it. After 34 years, it’s kind of hard to drop and walk away from it.”

He continues to work in the shop and office, offering his institutional knowledge to the organization’s 100-plus employees on just about anything they want to know. He also helps to source machinery parts.

Caskey said he simply works to avoid boredom. A couple years ago he was waylaid with an illness and forced to dial it back for two-and-a-half months. “I pretty much went out of my mind because I couldn’t do anything.”

He also kept his mind sharp and fingers nimble for the last quarter-century with sewing machine repair for his wife’s sewing and fabric shop. “You could never find one machine that had the same problem as the other,” he said. With so much specialized experience, he has developed more than a few opinions about sewing machine brands. “I didn’t like Singer,” he said. “Sorry to say, but they’re a piece of junk.”

His entire life, Caskey has gravitated toward the action. Even though he has scaled back some of his duties, he sees himself as a member of the Barr-Ag team. To contribute is important at any age, he said. “You should be looking for something to do to keep yourself active. If you don’t keep active, you’re dead. When I retire, I’ll be dead.”

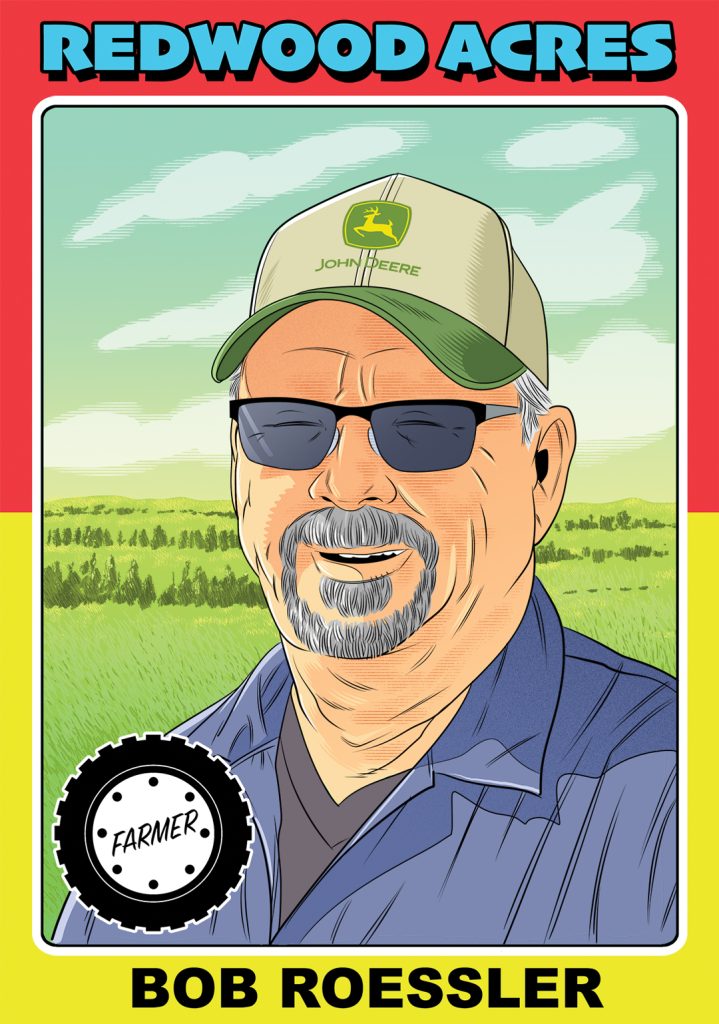

BOB ROESSLER, REDWOOD ACRES

Some farmers do manage to retire. Bob Roessler was one of them. When the Sexsmith area farmer sold off his feedlot in 2009, he did leave it behind. He didn’t, however, permanently retire. He worked for utility provider Aquatera in the city of Grande Prairie. After about five years, urban commuting and the humdrum feeling of being cooped up proved too much. He asked longtime friend and farm neighbour Greg Sears if he needed help. Sears did, and Roessler jumped back in the saddle as a farmhand in 2014. It felt like a homecoming party more than a new job.

“I tried a few other things, too, but radiated back to the farm because I like it out there,” said Roessler. “I much prefer driving out to the farm in the morning. I’m out there in the country where I’m raised, in the big rolling hills. You’re producing something valuable, and that’s what I like about it. In fact, even just today at noon, when I stopped to have an apple, I stopped on the top of the hill, and I did have pure pleasure just looking at the countryside. It’s just really nice. That’s fulfilling for me.”

These days, Roessler happily works full time–part time, an arrangement that has him at Sears’ farm from mid-April to mid-October, usually clocking five to eight hours daily. Seeding and harvest are exceptions when he typically puts in additional hours. While Sears employs extra people during the busy times, it’s often just the two of them, busily working together during the farming season.

Sears has been heavily involved in farmer groups, including Alberta Grains, and has routinely been away from the farm. It’s no issue for Roessler though, as he can oversee daily operations in Sears’s occasional absence. Roessler’s wife Lynda has managed to stay retired since 2000 and is heavily involved in the lives of their grandkids. Roessler joins these family activities in the farming off-season.

He does everything he used to do, except carry the title of boss. He operates drills and combines, mows the grass and more. You name it, Roessler does it.

Before selling off, he worked most of his career in the cattle industry. Despite long and busy hours, he found it rewarding and full of great people. However, he had little time to pursue interests outside the industry. “Your hobby is your farm; you put everything back into it,” he said, and added golf is the one pastime he has embraced. “I golf once in a while, but it’s not enough to keep me busy, so that’s why I went back to work.”

The sense of pride is no different, either. He still feels the same satisfaction in a job well done that he did 50 years ago. “When you take the grain off, there’s a lot of accomplishment there for me. It never gets old,” he said. “I love the animals in the country and that’s just what it is. It doesn’t really feel like work to me. I go up there and there’s some sweaty days and some dirty days and everything else, but that’s part of farming. I grew up with it, so I know exactly what it takes to seed and harvest the crop, and I’m there to do that.”

One drawback Roessler has found in continued work is that many of his friends are retired and often would like to meet for a cup of coffee or a round of golf, but he’s often unavailable.

He’s spoken with his boss, Sears, and made it clear he sees himself as “day to day” in his level of commitment. He does foresee a permanent retirement in the future. When? He can’t say.

“I’m probably not going to like it all that much, but I’ll probably go to the farm even if I can just sit on the lawnmower for a while and cut the grass. I don’t have to be the main guy. At 71, my health has been pretty good, but there comes time when you need to rest, too. The people I work for are good and we’ve known one another for our entire lives. I just really enjoy it. Some people call it work; I just call it fulfillment.”

Comments