INVASIVE SPECIES

BY EMILY R. JOHNSON • ILLUSTRATIONS BY JARETT SITTER

When Cardston County farmer Sean Stanford discovered downy brome in his wheat field last spring, he was bewildered. “I don’t know why, but this was the first year I’ve had it in this field,” said Stanford, an Alberta Grains Region 1 delegate. “You can control these things, but you have to do it at the right time of year, and it’s expensive to do.”

Downy brome was introduced to North America in the 1860s by contaminated European grain shipments. A heavy infestation of the weed can reduce wheat yield by 30 to 80 per cent. The weed can also be a problem for rangeland as it creates fuel for wildfires following its short growing season. Classified as a noxious weed in the Alberta Weed Control Regulation, downy brome is one of many invasive species that span weeds, insects, rodents, large mammals and even diseases, introduced to North America in the last several hundred years. These have caused many negative ecological and agricultural impacts.

Seventy-six invasive weeds are now listed under Alberta’s Weed Control Act. Those classed as noxious weeds are considered too widely distributed to be eradicated from the Prairies, although landowners are deemed responsible for their control. In contrast, prohibited noxious weeds are either not present in Alberta or in so few locations eradication may be possible. A landowner is responsible for the destruction of prohibited noxious weeds under the Act, which is under review.

Many invasive species, weeds included, can overwhelm crops and wild native plants despite not being listed under control regulations. Take kochia, which was listed from 1973 to 1980. The common dandelion was removed in 2010 because it is now so widespread it is considered endemic.

In addition to his fight with downy brome, Stanford inherited someone else’s kochia problem with a land purchase. Kochia was introduced to Canada as an ornamental, and according to a 2017 weed survey, it was then the most abundant weed in Alberta’s mixed grassland ecoregion. It is nasty. In drought conditions, kochia roots can form extensive networks in the soil as they hunt for moisture and nutrients. “It affects yield,” he noted. “Where the kochia wants to grow, no crop wants to grow. It’s bothersome to try and get rid of it and keep it from spreading, but if you don’t, you’d get no crop at all.”

AN ECONOMIC HIT

The Alberta Invasive Species Council (AISC) is a not-for-profit society that informs and educates Albertans about the destructive impacts of invasive species. An assessment it conducted in 2024 estimated invasive species cost Alberta an enormous $2.1 billion annually. The tally was based on an economic assessment completed 20 years prior and adjusted for inflation along with the increased abundance and diversity of invasive species in Alberta.

Most economic impact is associated with the loss of productivity of crops and rangeland due to invasive weeds. The agricultural sector is being hit disproportionately by the economic impacts of invasive species, according to Megan Evans, AISC executive director. “We know yield losses, management and prevention costs impact producers, and a large portion of costs also get transferred to consumers,” she said.

Evans stressed that while Alberta needs a more comprehensive assessment to be certain, the $2.1 billion estimate is likely low. “Invasive species’ economic impacts are on the same magnitude as the economic impacts associated with natural disasters, but they don’t receive the same level of concern, funding or support,” said Evans. “We really need to start taking invasive species more seriously.” Evans also noted that the global economic impact of invasive species on all sectors, including agriculture, is around $400 billion annually.

FARMERS KEY TO DETECTION

Agronomists, farmers, ranchers and other agricultural stakeholders play an essential role in the detection and monitoring of potentially harmful invasive species.

Brent McCallum is a research scientist with the Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) Morden Research and Development Centre and project lead of the Prairie Biovigilance Network (PBN). The PBN is a team of 17 AAFC researchers who work to reduce pest problems, namely insects, weeds and diseases, in western Canadian crops.

Because farmers are on the land, they are often first to spot these emerging threats. This makes them invaluable in the control of invasive species. “Farmers are closest to the ground, and they understand what’s going on in their fields,” said McCallum. “They’re the eyes that can alert us to these problems, so their role is crucial.

“Things are very dynamic; a pest that was under control is suddenly not under control as the population changes over time,” said McCallum. “If farmers and agronomists are constantly looking, then the industry is in a position to identify those invasive species if and when they arrive.”

To assist with pest surveillance research, farmers can contact commodity groups or submit invasive species observations through the Early Detection and Distribution Mapping System (EDDMaps) app. The app has a species identification feature and sends observation reports to verifiers for review. If confirmed, observations may be added to provincial distribution maps.

Samples can be submitted directly to the Alberta Plant Health Lab (APHL). They can also be submitted to the Association of Alberta Agricultural Fieldmen or municipal pest management departments, which can forward the samples to the APHL.

EARLY DETECTION, RAPID RESPONSE

Stanford was fortunate to identify the downy brome as a noxious weed in his field of spring wheat and acted quickly before it got out of hand. Early detection and rapid response, regardless of species, is considered the golden rule of invasive species control and eradication.

It’s somewhat like fighting a wildfire, said Ryan Brook, a leading wild pig researcher and professor at the University of Saskatchewan College of Agriculture and Bioresources. “With any invasive species or a forest fire, you really have only one option,” he said. “You detect it quickly, and then you act really fast and really aggressively until it’s gone.”

He noted the opportunity to eradicate wild pigs from the Canadian Prairies has been missed by at least a decade. “An unfortunate reality is that 15 years ago, a fairly small amount of effort probably could’ve gotten rid of all of the invasive wild pigs.”

The number of wild pigs on the Prairies is unknown, but it is estimated to be in the thousands. This is despite ongoing removal programs and a public campaign organized by AISC, Alberta Pork, the Province and the federal government. Dubbed Squeal on Pigs, it encourages landowners to report signs of wild pig damage. Brook hopes the proliferation of wild pigs serves as a warning for agriculture that invasive species must be taken seriously.

The Alberta Government may be taking notes, as it has intensified efforts this past summer to keep the province free of zebra and quagga mussels. Invasive mussels wreak havoc on aquatic ecosystems. They also damage and block irrigation infrastructure. In 2024, the Province formed a dedicated mussel task force, expanded watercraft inspection stations from five to seven, introduced a mobile inspection unit and launched an extensive public awareness initiative.

Alberta has instituted the highest fines related to mussel control in North America. The fine for failure to stop at an open inspection station while transporting watercraft has increased to $4,200 from $324. Failure to remove a drain plug while on the road is now a $600 hit.

Of 13,408 boats inspected during the 2024 boating season, invasive mussels were detected on 15, most of which travelled to Alberta from the eastern provinces. Alberta, B.C. and Saskatchewan are zebra- and quagga mussel-free, but vigilance is a must. “Zebra mussel infestation is a ticking time bomb,” said Evans. “It’s probably a matter of when, and not if. We need to be prepared to deal with that when it happens.”

CLIMATE ASSISTED SPRAWL

Climate change is reshaping ecosystems and growing conditions. This creates new opportunities for invasive species to outcompete native ones. As temperatures rise and weather patterns shift, these non-native invaders can find it easier to establish themselves in new environments.

“When the climate gets warmer, some pests can move farther north, expanding their range,” said McCallum, who is concerned about the situation. He monitors for a specific strain of wheat leaf rust attacking durum in the southern United States and Mexico. “This strain is virulent on durum wheat and can spread from south to north on wind currents.

Our current wheat leaf rust population in Canada isn’t virulent on durum wheat, which has allowed it to escape rust pressure here. However, if this strain came into Canada from Mexico, it could threaten our durum crops.”

The northward migration of invasive species is not the only concern for agriculture and native ecosystems.

“Invasive species don’t care about borders and jurisdictions, they’re just going to keep moving,” said Evans. It’s important to note not all introduced species become invasive. They often possess traits that give them a competitive edge as environments change. These include rapid growth rates, prolific reproduction and adaptability. These competitive traits allow invasive organisms to outpace native species in adaptation to new climate conditions. Evans cited research findings that non-native species expand their range 100 times faster than native species.

This underscores the need for proactive monitoring and adaptive management strategies. It’s a rapidly evolving situation, and the Prairies are under threat.

INTEGRATED PEST MANAGEMENT

When managing pests, it’s important to take a holistic approach, stressed Meghan Vankosky, a research scientist in field crop entomology with AAFC’s Saskatoon Research and Development Centre. She is also co-chair of the Prairie Pest Monitoring Network and a PBN researcher.

The agriculture industry has coined the term integrated pest management to reflect the wide variety of factors involved to achieve longterm success in pest control. “It’s about surveillance and monitoring, but also understanding pest biology, discovering and implementing control methods and evaluating their effectiveness,” said Vankosky.

This approach creates a positive feedback loop in which the system constantly improves. Vankosky points out that pest management is multifaceted and deals not only with invasive species but also endemic or migratory pests that require annual management, and those that unexpectedly resurface. One such pest is the Hessian fly, or barley midge, a pest that arrived on the continent from Europe in the late 1700s.

Given the complexity of pest management, priorities often shift year to year depending on which insects pose the most significant threat. Evans said integrated pest management planning requires diverse and effective tools farmers and landowners can use to successfully manage invasive and endemic pests and allocate resources effectively. “While it’s important to know what species you have, it’s also crucial to know how much you have and how they reproduce,” she added.

For invasive weeds, control may include hand pulling, spraying, crop rotation and additional techniques. In southern Alberta, goats have been trained as a biocontrol method for leafy spurge, a designated noxious weed. Their strong teeth and acidic stomachs destroy the plant’s seed head.

It’s essential to monitor the success of various control methods and adjust strategies based on the species, growth stage and crop type. “We need to outsmart invasive species, and we can do it, but we can’t just take a blanket approach to everything all the time,” said Evans.

GONE UNNOTICED

The fight to protect Alberta’s native ecosystems and agriculture industry from invasive species is complex to say the least. Success stories in invasive species management are frustratingly hard to find, although farmers regularly score small victories, said Evans. “In invasive species management, our successes are invisible, but our failures are everywhere. If we’ve eradicated something, you don’t even see it, but if we haven’t, it’s a mess out there.”

While successful eradication may not be visible, once an invader has established itself the consequences may also go largely unnoticed. Depending on the species, however, ecosystems and landscape can be drastically changed. Many invasive species are generalists whose impacts go beyond agricultural crops, stressed Vankosky. They may even be responsible for the elimination of native species. “They could be removing plants and insects from the community that we’re not really paying attention to. When you lose a species from the ecosystem, that can have all kinds of impacts on the other species that relied on it.”

It’s up to the community to the community to keep watch on what’s happening in our fields, waters and rangeland. The fight against invasive species is an ongoing battle that requires persistence and action from the agriculture industry, conservation groups and government, but also from the greater population.

“We need all Albertans to be diligent,” said Evans. “If you see something out of the ordinary, if it’s a rat, if it’s a pig, if it’s a weed you’ve never seen before; help be our eyes on the ground and let us know if you see something unusual.”

To learn more about invasive species, visit abinvasives.ca.

RAT-FREE FOR MORE THAN 70 YEARS

The Rat Control Program was established in 1950 and has since maintained Alberta’s rat-free status. Historically, much of its work was concentrated in the Rat Control Zone along the province’s eastern border with Saskatchewan, a 600-kilometre by 29-kilometre area that runs from Cold Lake to the Montana border.

Concerns about rats crossing the Saskatchewan border persist, and a new campaign dubbed Rat on Rats! has been launched. Overseen by the Alberta Invasive Species Council, it is funded by the Sustainable Canadian Agricultural Partnership. The initiative aims to raise awareness about rats that hitchhike into Alberta on vehicles and other modes of transport. Rat on Rats! urges Albertans to remain vigilant and report rat sightings and signs of their activity. “We’re talking not only to rural Albertans but urban and new Albertans as well,” said Evans.

The Rat Control Program mainly focuses on the Norway Rat, an invasive species thought to have originated in parts of Asia. It was introduced to the east coast of the continent in 1775. They have subsequently become a widespread threat to North American agriculture. Although unable to overwinter in cultivated fields, rats invade human structures, feed on grain and cause damage to insulation, wired equipment and wood. They spread numerous diseases, and with their droppings, are known to contaminate up to 10 times the amount of feed they consume.

Alberta’s rat-free status indicates the rodent has been unable to establish itself, but localized infestations do occur. One such incident is an ongoing infestation at a Calgary recycling facility. “This is simply an example of an invasive species management program that is working,” said Megan Evans, executive director of the Alberta Invasive Species Council. “This is an infestation we’re on top of, and the goal is eradication.”

In 2023, Albertans reported 450 rat sightings. Twenty-three were confirmed to be rats, while the majority were confirmed to be muskrats, a non-invasive rodent.

Report rat sightings or signs at rats@gov.ab.ca or 310-FARM (3276).

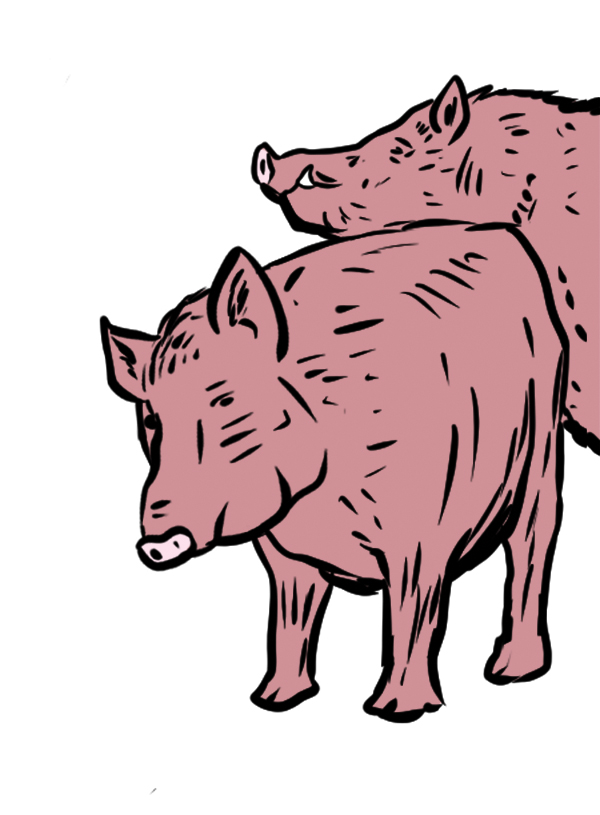

WILD PIGS AN ECOLOGICAL TRAIN WRECK

Impressive progress has been made in the battle with invasive pigs in Alberta. Since 2018, 410 wild pigs have been captured and humanely euthanized, the majority in Woodlands County in north-central Alberta.

Ryan Brook, a leading wild pig researcher, praised the province’s control effort over the last five years but stressed it doesn’t guarantee Alberta’s wild pig population is under control.

An important component with which to measure the success of trapping efforts, their number is unfortunately not known. “We don’t have data to estimate how many pigs there are,” said Brook. “As of today, we don’t have any meaningful idea of whether things have stayed the same, improved or worsened. There is no doubt they are in the thousands, but how many thousands we don’t know.”

Elk and deer may cause limited damage when they graze on crops. In contrast, the spread of wild pigs has been described as an ecological train wreck due to their broad environmental impact, noted Brook. They destroy crops, alter landscapes and negatively affect various wildlife species from ground-nesting birds to adult whitetail deer. Their rooting behaviour tears up the ground and leaves the soil susceptible to invasive weeds.

“When pigs have been to your environment, you see it just torn up,” said Brook. “The ground takes years to recover.” They also contaminate water bodies with E. coli and salmonella bacteria as they wallow and defecate.

Brook accepts that the pigs are here to stay. “The thinking has to shift to living with these things and continuing to minimize the impacts.” He calls for more targeted control efforts, better data collection and a focus on minimizing their impact through aggressive and co-ordinated control tactics.

Report wild pig sightings and suspected damage at wildboar@gov.ab.ca, 310-FARM (3276) or contact your local municipality.

Comments