A GROWTH INDUSTRY

BY KAREN DURRIE

Cellular agriculture is poised to become a growth industry. The term refers to the engineering of plant or animal cells to create a food product or ingredient. The technology has been used for decades to produce food enzymes and proteins. For example, since the 1990s, 80 per cent of the rennet used in cheese making worldwide is produced by protein fermentation rather than traditionally sourced from calves’ stomachs. Cellular agriculture is also known for its potential to commercially produce animal proteins that closely mimic the meat of farmed animals.

With a recently signed memorandum of understanding to create the Institute of Cellular Agriculture, Alberta is positioned to become a top location for the advancement of cellular agriculture. The three joint venture partners hail from across the value chain. The first is CULT Food Science Group, an investment platform for the development and commercialization of cellular agriculture technologies and products. Also a participant, New Harvest is a non-profit organization that advances cellular agriculture through research, collaborative projects and public and private sector engagement. The two organizations have joined forces with the University of Alberta to locate the project at the University’s Agri-Food Discovery Place.

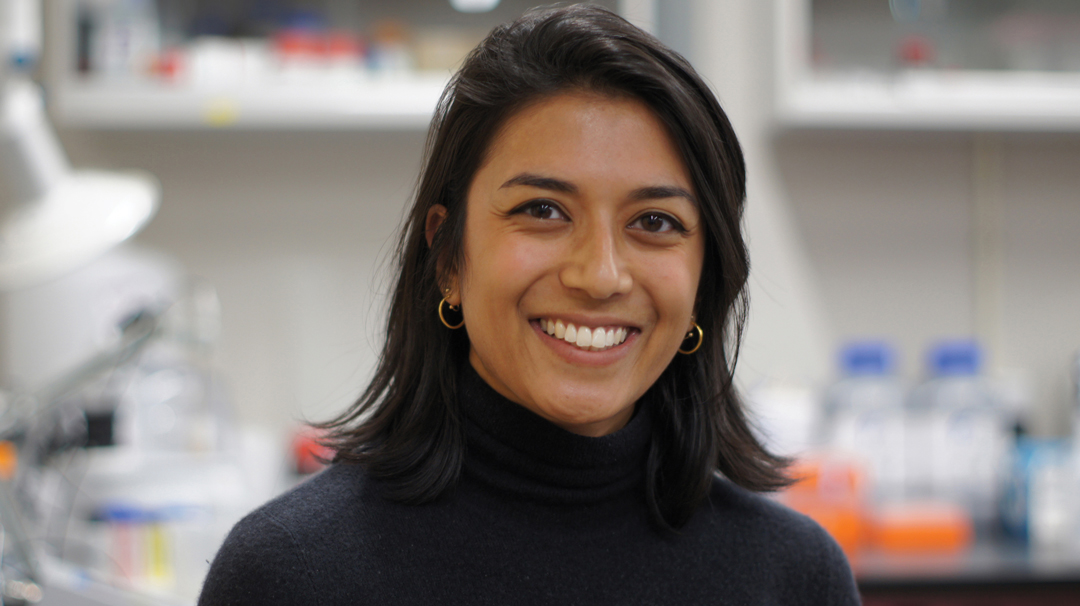

Credited with coining the term “cellular agriculture,” Isha Datar is executive director of New Harvest. Datar grew up in Alberta and studied cell and molecular biology at U of A. She believes Agri-Food Discovery Place is the perfect location in which to build a cellular ag research and development facility. “It’s a ripe, rich environment to push through an interdisciplinary idea like cellular agriculture. It’s a farm in the city and has bioprocessing capabilities and bioreactors, a meat slicer and smoker—a perfect coming together of things that cellular agriculture would require.”

Cellular agriculture is considered an important tool to create diversity and improve efficiency in the global food system, said Datar. “Our current livestock supply chain is kind of fragile, and we don’t have a plan B. This creates [the need for] more options in our food sources. We need diversified sources just like we do for energy.”

Datar believes the Institute will add value to Prairie agriculture, in part through the development of new agri-food products for global trade. She imagines a facility that looks like a brewery equipped with large stainless-steel bioreactors. Within these, plant and animal cells will be fed amino acids and starches to produce products such as chocolate, honey, vanilla, milks, eggs and meat.

The products needed to fuel such systems can potentially be supplied by farmers, said Datar. “We need to figure out what that process looks like. Lots of the raw materials that go into these bioreactors are shipped in from other countries. We would love to collaborate with the various grain, starch and protein producers right next door,” she said.

A timeline for the Institute’s launch has not yet been set. “We’re exploring working with some partners to establish the Institute,” said Heather Bruce, chair of the University’s Department of Agricultural, Food and Nutritional Sciences. “We’ll be doing targeted hiring in the future and hope to be able to support students, launch new courses in cellular agriculture and train graduate students so we are ready for the startups establishing themselves very quickly in Canada and globally.”

As the Institute grows, renovations will be made to accommodate the addition of new equipment to, for example, increase the institute’s tissue culture capacity, its protein purification capabilities and to add bioreactors.

Comments