GENETIC ADVANCES MULTIPLY

BY SARAH WEIGUM • PHOTO COURTESY OF SARA TETLAND

Two research projects funded by the Alberta Wheat Commission (AWC) have made significant advances in cereal crop genetics. Overseen by Pierre Hucl of the Crop Development Centre (CDC) at the University of Saskatchewan, the first of these examined the viability of a new dwarfing gene in bread wheat. Secondly, Nora Foroud of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) developed new wheat and barley lines with improved resistance to Fusarium head blight (FHB).

HOW DOES SHORTER WHEAT MEASURE UP?

Hucl’s project focused on a dwarfing gene that was discovered as a mutation in U.S.-grown durum wheat in the late 1980s. Hucl took this gene, Rht18, and crossed it into CDC Utmost, a CWRS variety. This was the first introduction of this gene into a Canadian bread wheat variety.

“We developed lines that carried the gene and others that did not in a CDC Utmost background,” said Hucl. Known as near-isogenic lines, these two iterations of CDC Utmost carry the same genetic material with the exception of the introduced dwarfing gene.

“Then you can really tease out what the effects of the gene are. Does this gene have an effect other than just reducing plant height?” said Hucl.

The near-isogenic lines first hit the field in 2016 as part of a graduate project conducted by Hucl’s student Sara Tetland. AWC contributed $61,000 to the project, which concluded in 2019. The Saskatchewan Agriculture Development Fund and SaskWheat also funded the research.

The lines with Rht18 were, on average, 15 centimetres shorter than the control lines. This produced a higher harvest index, determined by dividing the dry grain yield of a plant by the amount of its above-ground dry plant material. In two plants with identical grain yield, the one with less above ground plant material would display a higher harvest index.

“The [harvest index] is important because plants use the products of photosynthesis for either growth or reproduction,” said AWC research program manager David Simbo. “If a plant is engineered to grow short, a larger portion of the products of photosynthesis will be used in reproductive growth, which is grain yield.”

While shorter stature can improve wheat harvestability, Hucl’s research uncovered a downside to the petite plants. The ones carrying the dwarfing gene had 36 per cent higher FHB infection levels and DON levels increased by 16 per cent within inoculated nurseries. Hucl believes the increased disease prevalence is a result of the heads being closer to the ground where rain can more easily splash inoculum from crop residue onto the flowering plant. Because the shorter plants lack the physical escape mechanism of height, Rht18 will be best deployed in crosses with lines that have strong genetic resistance to Fusarium, unlike CDC Utmost, which is moderately susceptible.

The project also included quality testing that is standard on all CWRS lines.

“Knowing now that there is a fairly large durum chromosome segment that comes along with this gene, you have to make sure you’re not bringing along a protein, for instance, that is good for pasta production but isn’t for bread production,” said Hucl. The grain from shorter plants had a small drop in one indicator of gluten quality and a slight increase in falling numbers. As a followup to the project, milling and baking tests were conducted on a subset of near-isogenic lines, which raised no red flags.

One breeding line with the gene made it to pre-registration trials in 2019 but failed to advance due to low test weight. Such “near miss” lines typically become a parent in future crosses, said Hucl.

STRENGTH IN NUMBERS

Research scientist Nora Foroud works at the AAFC Research and Development Centre in Lethbridge at the heart of Alberta’s irrigation network. FHB and other diseases can potentially wreak havoc on warm, wet irrigated crops. With the participation of wheat and barley breeders, Foroud has worked to improve resistance to FHB.

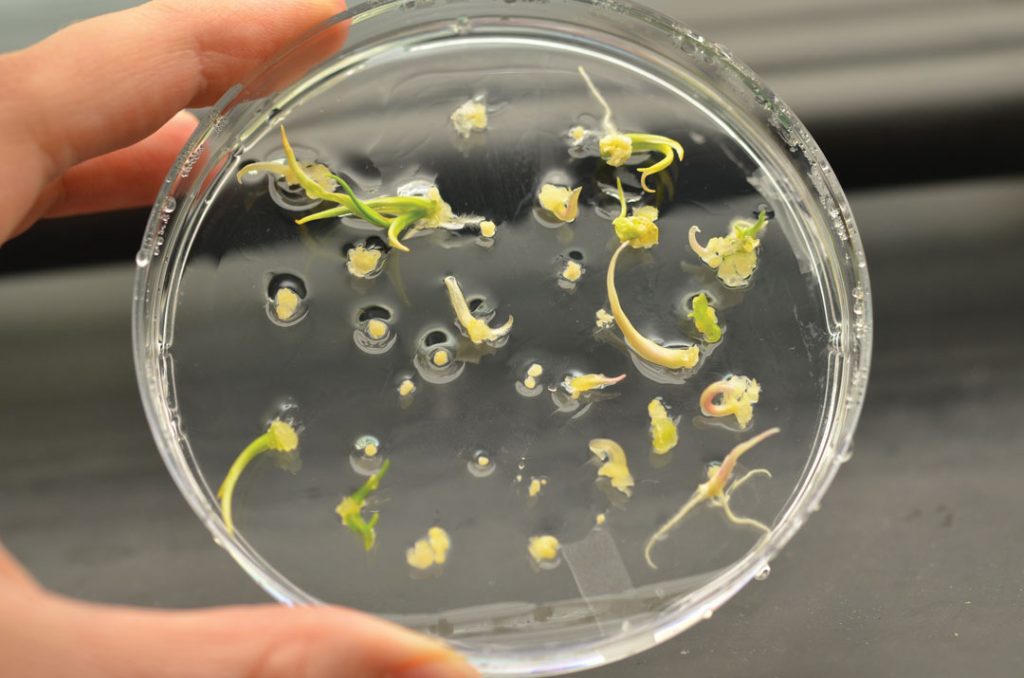

Since 2014, Foroud has received initial crosses of wheat lines, or F1 hybrids, from plant breeders. Using the immature pollen cells in these plants, she has cultured haploid embryos in her lab. The haploid embryos germinate into haploid plantlets from which scientists develop doubled haploid plant lines. The creation of doubled haploid lines is a common method of modern plant breeding that allows researchers to develop plant lines with fixed genetics in one generation rather than over several generations of inbreeding. In a process known as in vitro selection, Foroud introduces Fusarium mycotoxins to embryo cultures while they develop.

“The theory is that the plants that develop from those microspore cultures have a higher frequency of plants that have resistance to FHB,” said Foroud. Carried out between 2017 and 2020, her project received $120,000 from AWC as well as support from Alberta Innovates and SaskWheat.

The three years of work produced about 1,100 barley lines and 3,000 wheat lines that were returned to breeding programs across the Prairies for additional screening. AWC’s Simbo described Foroud’s contribution to the grain industry as significant.

Twenty-one wheat lines produced by Foroud’s in vitro selection lab are now in registration and pre-registration trials. Barley was added to the research project more recently, so lines for the crop are not as far along in the screening and registration process.

“I’m fairly optimistic that with the number of lines we’ve developed we’ll have more lines feeding into those pre-registration and registration trials,” said Foroud. Last year, she also expanded her research to include durum wheat. AWC has committed to funding Foroud’s in vitro selection research for another three years.

Comments