BY SARAH HOFFMANN

more electricity, but so do soils with high

salt content that tend to be in saline areas.

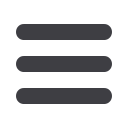

To effectively manage areas with varied

EC ratings, Willness ground-truths his

data by soil testing, talking to the farmer

to understand the way the land has per-

formed historically and getting a visual

understanding of the depressions, mid-

slopes and knolls of the field. He combines

this data to create a prescription map,

noting areas of the field that will be more

or less responsive to nutrient inputs.

“Let’s say you test a field and the tops of

hills are low in phosphorus and sulphur

and the depressions are the opposite,” said

Willness. “The fact that it’s a wet, average

or dry year does not change the fact the

depressions are not the most responsive to

phosphorus and sulphur, so you could just

put a maintenance rate on there.”

DATA DECISIONS

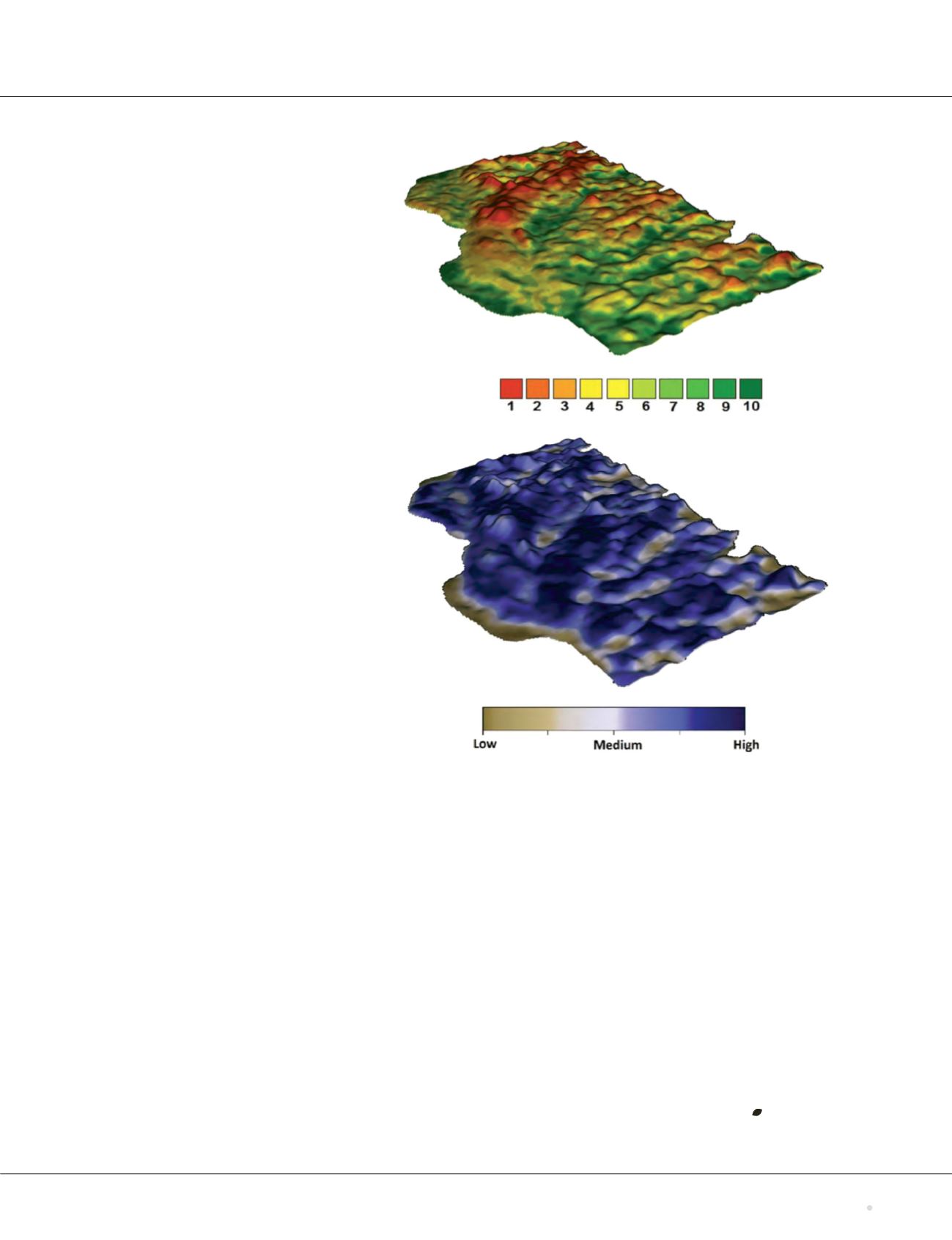

Marrying soil and vegetation data is a

challenge for farmers and agronomists

alike. The sheer quantity of data that can

be collected is daunting, not to mention

the various ways it can be interpreted,

quantified and layered. Working in the

Edmonton and Peace regions, Nuffield

scholar and agronomist Kristina Polziehn

uses aerial mapping combined with her

on-the-ground experience. Her company,

Axiom Agronomy, provides standard

services such as soil sampling and crop

scouting as well as aerial imagery from

drones and manned aircraft.

She cited a lack of reliable data as the

main challenge to the utilization of map-

ping by farmers. Ideally, this data should

be gathered over a long time frame and

include properly assigned causes for the

variations in the images and information.

“People say you need 10 years of good

data,” said Polziehn. But while there are

decades of satellite imagery available, she

noted that for most of that time, there’s

been no one in the fields determining

why variations exist. “Were those a result

of disease? Surface disturbance? Bush

removal?

“If you’re using data in order to build a

layer into a yield map and it is bad data,

you might not be ahead in putting that in,”

said Polziehn. “Doing a little bit of histor-

ical ground-truthing and utilizing quality

data is important.”

Polziehn said that widespread on-farm

adoption of remote sensing and the maps

it produces is fairly low, and for good

reasons. For example, creating prescrip-

tion fertilizer maps and uploading them

to seeding equipment can be time con-

suming and the process varies from one

brand of equipment to another. On large

farms with multiple operators, it can

be difficult to train everyone and make

sure variable-rate application is always

engaged. As well, analyzing data is time

consuming.

“Even myself, I have access to so much

data, but even if I had a satellite image

come in every second day, would I be

looking at that email? Probably not.”

While she continues her research into

the world of remote sensing and farmers

continue to work toward applying the data

effectively on their farms, it’s important

to remember that no map is a silver bullet.

“Remote sensing is not a stand-alone

technology,” said Polziehn. “It’s to be com-

bined with other pieces of information.

It’s maybe going to take time to figure out

where it layers in.”

Kristina Polziehn’s Nuffield Scholarship is

supported by the Alberta Wheat Commission.

As high electrical conductivity ratings don’t necessarily correspond with high soil potential, CropPro’s

CoryWillness ground-truths mapping data with soil tests and farmer input.

Winter

2018

grainswest.com43