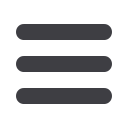

Glenbow Archives NA-2604-30

Feedingthefieldcrew

FROM THE TIME FARMERS FIRST

broke Prairie soil, harvest-time field

meals became a tradition.

Feeding the threshing crew was a big,

important job. Women, assisted by girls,

often cooked for these outfits. Presiding

over the cook shacks, they rose early to

bake dishes in wood stoves and served

hearty meals at tables or serving windows.

Preserved in the photo archive of Cal-

gary’s Glenbow Museum, this photo of

farmer Tom Whittle and his harvest crew

at lunch was taken near Foremost in

1917. The image also accompanied a 1986

story entitled “Folklife of The Threshing

Outfit” in

South Dakota History

, the jour-

nal of the South Dakota State Historical

Society. Written by Thomas D. Isern, he

noted that threshing was prevalent from

the late 1890s through the Second World

War and beyond. During that time, cus-

tom threshing crews travelled the West,

complemented by many farmers-

helping-farmers crews.

Feeding crews was a daylong job accord-

ing to Anna May Handley, who worked as

a hired girl in Saskatchewan in 1928 and

whose recollections Isern quotes. “Break-

fast consisted of bacon, eggs, hash brown

potatoes, and a gallon of coffee. For dinner

at 11:00 a.m. we cooked a 15 pound roast,

two types of vegetables and what seemed

to me to be a half bushel of potatoes. (I

had to peel them.) All the men liked pie

for dessert, so we baked three pies every

day. At 3 p.m. we took lunch out to the

field. This was another gallon of coffee,

sandwiches, and cookies. For supper we

had cold meats, potatoes, salads, and cake

for dessert.

“The highlight of our day was when

we took lunch out to the threshing crew.

We waited until the men had finished

eating so we could bring the plates home.

I enjoyed the ride home on those beautiful

autumn days, when there wasn’t a breath

of wind and a haze hung over the land-

scape. It felt good to be alive.”

When boarding threshing crews,

work for the farm wife multiplied. “She

did not relish social contact with these

individuals,” wrote Isern, hinting at their

roughness. Not surprisingly, farm wives

were supporters of new farming technol-

ogy such as gas-powered combines that

appeared in the late 1920s, ending the

threshing era.

AGAINST

THE GRAIN

Fall

2017

Grains

West

46