BY GEOFF GEDDES

focus of any revised deal should be a har-

monized approach to health claims and

nutrition labels,” said Kurbis.

From an American wheat farmer

perspective, O’Connor sees positives for

all three countries in the agreement. “We

were all part of the TPP (Trans-Pacific

Partnership), and while the U.S. stepped

away from that, there were sanitary and

phytosanitary provisions that could be

incorporated in a revised NAFTA for the

benefit of all.”

HOPE AND HOMEWORK

While concerns remain, there is much

hope the right approach will bear fruit.

“Canada must do its homework and

come to the table with clear negotiating

objectives and desired results,” said Rice.

“We must be confident that we can forge a

modernized NAFTA, which will preserve

the North American market for another

20 years.”

While there was initial concern about

reopening NAFTA from producers on both

sides of the border, that may be chang-

ing. “As time has gone by, that concern

has been replaced with some optimism,

especially in light of the strong support for

the deal from the U.S. agriculture sector,

which universally endorsed it,” said Dahl.

“We can improve NAFTA, but we must

not do anything to impede trade or move

backward.”

In light of global activity on trade in

recent months, some feel that cautious

optimism is warranted. “If there is one

thing that has characterized trade-related

developments over the last year or so,

it’s the difficulty that even trade veter-

ans have in predicting outcomes,” said

Kurbis. Whatever that outcome may be,

Canada is hoping that when the smoke

clears, the only thing broken will be the

seal on the champagne to celebrate a job

well done.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF SUPPLY

MANAGEMENT

In a world where deregulation is

often the norm, Canada’s system of

supply management has been a point

of contention in international trade

negotiations.

It’s a system that is especially suited

for the dairy industry. When advances

in technology and farm management

led to a steep rise in farm production

in the late 19th century, the Agricul-

tural Stabilization Act was passed in

1958 to provide a minimum income

and a measure of financial security for

farmers. While the Canadian govern-

ment couldn’t afford to subsidize agri-

culture in the long run, it did the next

best thing by giving farmers the tools

to better negotiate with businesses and

gain a fair share of consumer dollars.

This was the impetus for supply

management, and though the reviews

are mixed, it has been increasingly

criticized as contrary to the principles

of fair trade and open markets.

That criticism has somewhat

impeded Canadian negotiators on

the world stage, most recently with

the TPP. Because countries like New

Zealand and the United States wanted

guarantees of major dairy concessions

from Canada that would affect our

supply management system, Canada

was largely an outsider to the negotia-

tions until late 2012.

Since then, the United States has

made it clear that the removal of trade

barriers against the American dairy

industry is critical to that country’s

participation in trade deals. Now

that the United States has withdrawn

from the TPP and asked to renegotiate

NAFTA, what this means for the fu-

ture of supply management in Canada

is an unknown. Will it be preserved at

the expense of other trade opportuni-

ties? Will it be abolished or modified,

and, if so, what will be the impact on

industries that rely on it like dairy,

poultry and egg production?

Stay tuned.

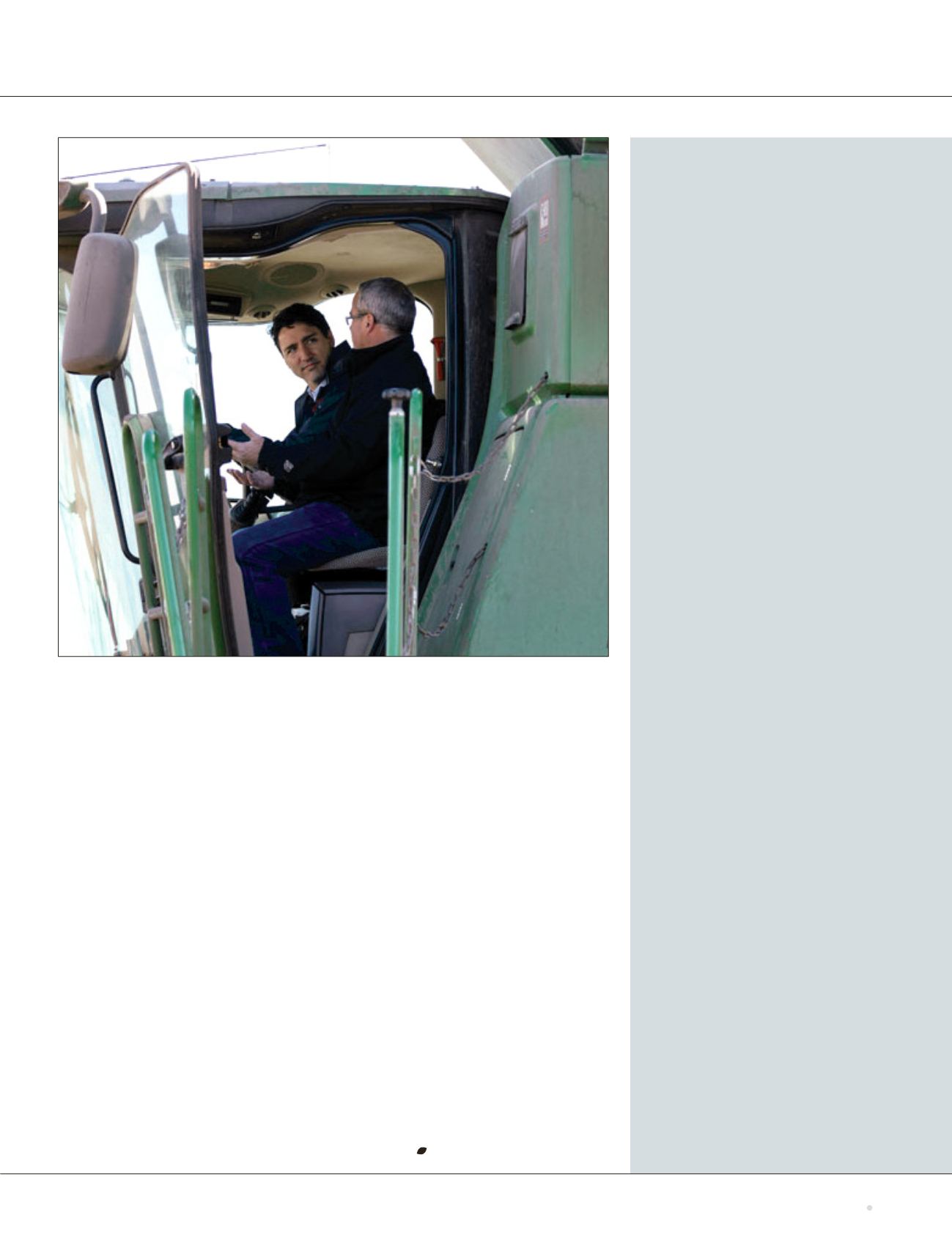

Photo:GovernmentofCanada

PrimeMinister Justin Trudeau visits the Lewis family farm in the Gray, Saskatchewan area. Under NAFTA, Canadian

grain farmers have enjoyed duty-free grain movement for almost 25 years, and do not want this to change.

Fall

2017

grainswest.com39