The Food Issue

2016

Grains

West

38

zero tillage, the practice of minimum soil

disturbance by forgoing annual tilling—

but that progress isn’t celebrated.

“Farmers have done a great job at

adapting their land management to shift

away from tillage, but consumers are

completely unaware of that shift—they

don’t know there could be major dust

storms every summer or ditches full of

eroded soil. Those things hardly happen

now because of changes farmers have

made,” he said.

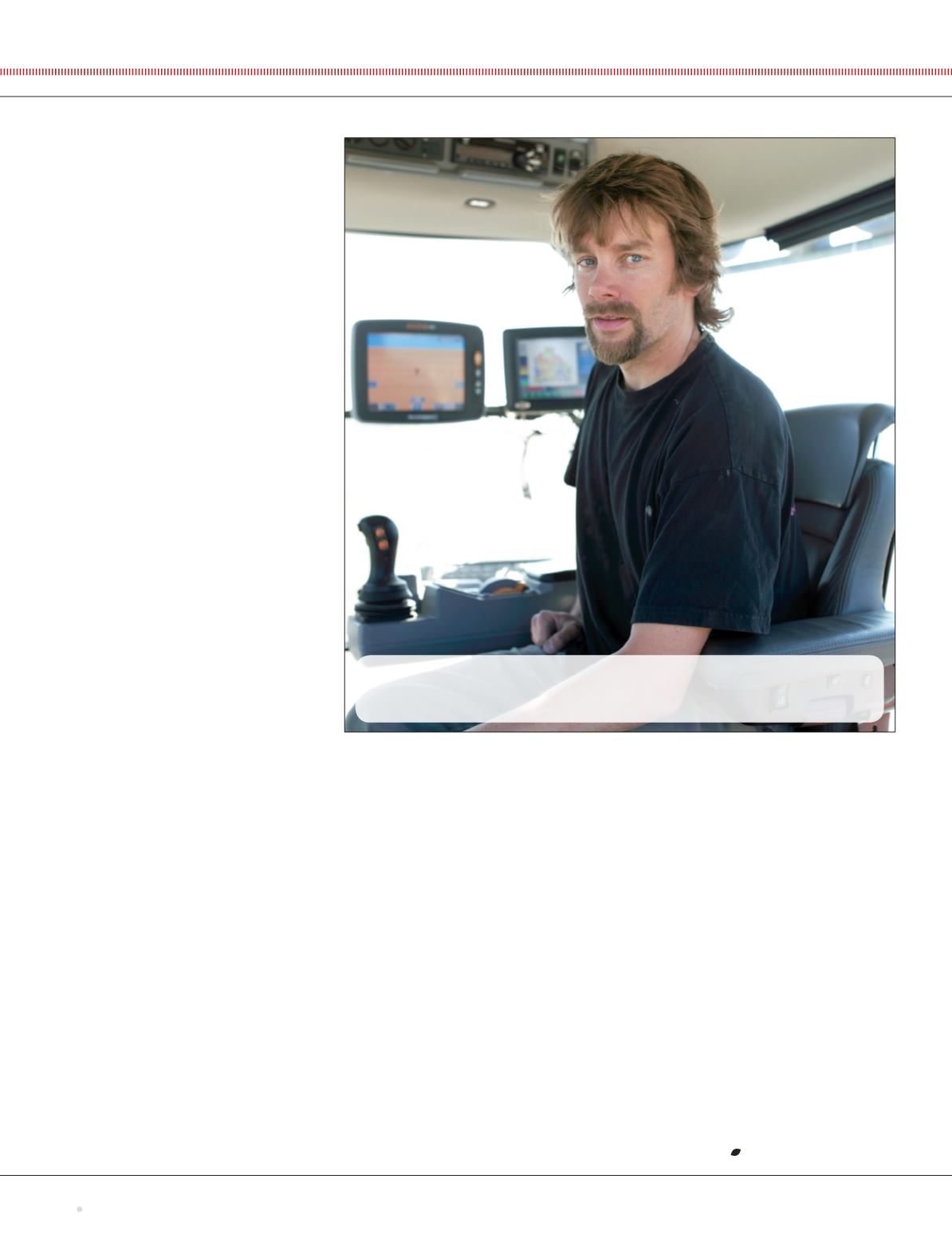

Patrick Kunz farms near Beiseker,

AB, and he’ll be the first to tell you he

welcomes questions about how he farms

and why he makes the management

decisions he does. He’s also keen on

change—recognizing that criticism is

sometimes warranted and that farmers

need to be open to trying something

new and shifting gears away from how

they’ve always done things.

Agriculture—the production of

food—happens in a biological system.

Biology is life; every change, an addition

or a subtraction, impacts something

else, for worse or for better. Too often,

when a particular tool—herbicides

or biotechnology, for example—is

criticized, the conversation centres on

the perceived risks or the unknown.

But what many of these concerns or

these calls for bans and avoidance fail

to take into account is the cascade of

consequences that can occur if farmers

stop using a certain tool.

Let’s use glyphosate, the popular

weed killer commonly known by its

trade name Roundup, as an example.

This non-selective herbicide is quite

likely the only crop chemical many

urbanites can name. Ignoring some of

the controversy for a moment, Kunz said

he’d like to see consumers understand

that the reduction in tillage on his farm

means adapting his weed management

practices as well.

“We’re still working at improving

land impacted by tillage,” Kunz said.

Glyphosate and other herbicides allow

him to reduce or eliminate tillage on

his land. That means using less fuel to

produce the same crop. It also means

his land stores more carbon in the form

of soil organic matter. Less tillage also

means less erosion or movement of soil

and soil nutrients through wind or water

movement. Tillage isn’t a chemical and

it’s not made in a lab, but it can have

negative environmental consequences,

and Kunz wants everyone to know.

He understands that consumers

have concerns and questions about

farming, and his goal is to show people

that farmers like him are committed

to constantly improving. “We haven’t

reached some pinnacle of farming,”

Kunz said. “I don’t think for a moment I’m

farming how I will be farming in 20 years,

and that’s not a bad thing.”

Unfortunately, Kunz has limited means

of connecting with consumers these

days. “Twitter is great, but there’s so

much nuance in farming, so many trade-

offs. You can’t explain that complexity in

140 characters,” he said.

To that end, Kunz has organized an

informal gathering of friends and friends-

of-friends to join him at his feedlot for

a tour and some productive dialogue.

Kunz hopes the face-to-face interaction

will allow him to share and explain more

of the complexities of farming, so that

the next time these consumers have

questions or concerns, they’ll reach out

to him first instead of just assuming the

worst of the farming industry.

And he won’t stop his one-man

awareness campaign anytime soon.

“I’ve got four kids. I farm with my

brother and he has three kids. The land

we farm is the land they will farm, we

hope, and we really do want to leave it

in better shape for them than it is even

now,” he said.

IN THE DRIVER’S SEAT:

Patrick Kunz is happy to answer any questions consumers might

have about his farm and the management decisions he makes for his operation.

Photo: Adrian Shellard.