Spring

2016

Grains

West

36

Feature

F YOU DON’T KNOWWHAT

MRL stands for, you can be

forgiven. Maximum residue

limits have been, until recently, not

something that most grain farmers in

Western Canada have had on their radar.

If you bought registered crop protection

products and used them according to

the label, all was well.

That’s not entirely accurate, of course.

Whether you knew it or not, establishing

and monitoring global MRLs has been an

ongoing process since the 1960s. In the

absence of a problem, it’s not something

many farmers would have had to worry

about. In 2011, however, MRL issues

following glyphosate use on pulse crops

destined for Europe brought the issue

to the fore. Then, in 2015, the lack of

an MRL in the U.S. for the plant growth

regulator Manipulator prompted grain

buyers to refuse grain delivery and ask

for declarations of use.

Can these trade disruptions be

avoided? To a degree, yes, but MRL

setting and management is a complex,

global issue. It’s important to first

understand how the MRL regulatory

system works.

HOWMRLS ARE SET

Each and every crop protection product

registered in Canada is subject to an

MRL—an allowable amount, in parts per

million, of residue on the harvested grain

or oilseed.

I

In Canada, once a new crop

protection product is created, the crop

protection company submits reams of

data to the Pest Management Regulatory

Agency (PMRA) in support of product

registration. The PMRA then not only

assesses the product’s crop safety and

other parameters, but also its safety to

human health. “Health Canada must

determine whether the consumption

of the maximum amount of residues,

that are expected to remain on food

products when a pesticide is used

according to label directions, will not be

a concern to human health,” reads the

PMRA website.

Countries around the world can

establish their own MRLs through

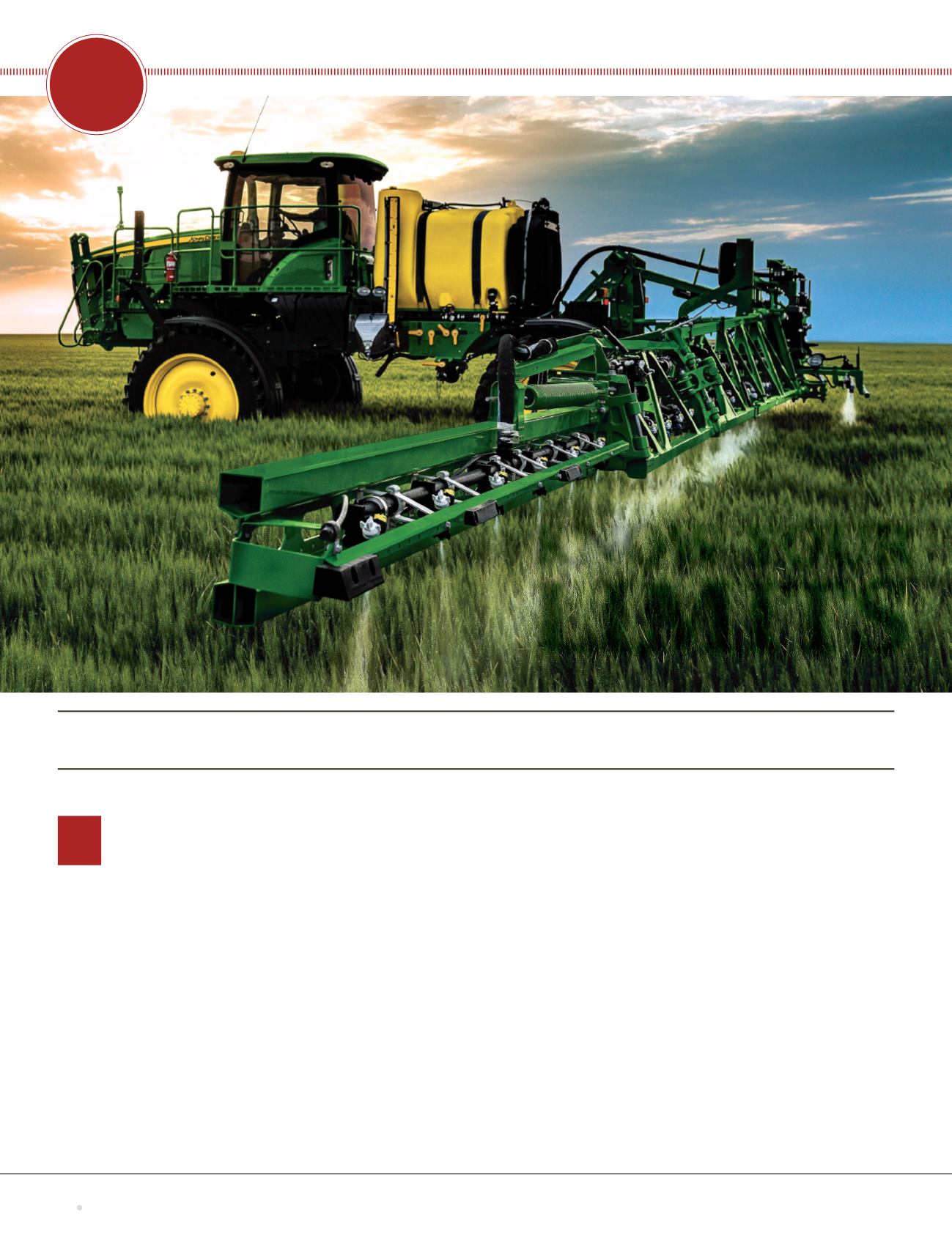

BY LYNDSEY SMITH • PHOTOS COURTESY OF JOHN DEERE CANADA AND THE CANADIAN GRAIN COMMISSION

KNOW YOUR

LIMITS