By GeoFF GeDDes

TECH@

WorK

Future farming

THOuGH THeY maY sOuNd liKe

something from the

Terminator

movies,

driverless tractors are far from science

fiction. That point was driven home

recently with the unveiling of autonomous

technology at the Farm Progress Show

near Boone, Iowa.

“Finding skilled operators for farm

equipment today is getting harder,” said

Luke Zerby, who manages the Precision

Land Management program for New Hol-

land Agriculture.

Using roof cameras, optical detec-

tion devices and cutting-edge software,

driverless tractors can be programmed to

perform tasks like tilling or planting and

are operated remotely by producers.

For some, it may conjure images of fu-

turistic machines running amok. The real-

ity, according to Zerby, is more technical

than magical.

“Operators view everything through

their home computer or tablet, so they

know exactly what’s going on,” said

Zerby. “If an animal crosses the tractor’s

path or a power line appears that wasn’t

accounted for in the programming, the

tractor will recognize that and stop.”

Using a cab-top radio for Wi-Fi commu-

nication, the tractor sends an alert to the

operator asking for direction. The farmer

can then have the machine plot a new

course around the obstacle or plot one

himself.

It probably sounds remarkable to those

outside of agriculture. Many insiders,

however, see it as a natural progression.

“The idea of precision technology

started in 1994,” said Leo Bose, marketing

manager for Case IH’s Advanced Farming

Systems. “By the early 2000s, it evolved

into auto-guidance systems with hands-

free technology in the cab.”

Fast forward to 2016 and the possibili-

ties are intriguing for the producer’s bal-

ance sheet. “It’s about driving efficiencies

that impact the bottom line,” said Bose.

Bose also cited a shortage of quality

labour as a key issue addressed by this

technology. Yet he quickly put fears of

“machines replacing humans” to rest.

“What it actually does is allow farmers to

redeploy human assets on-farm to boost

efficiency,” he said.

While those marketing the technology

tout the potential, some end users have

mixed emotions.

Penhold-area grain farmer Wade

McAllister can imagine the benefits the

technology could provide for his operation.

“I’m not sure about using it with more

complex equipment like air seeders, but it

would be nice with a grain cart to free that

person up for other work,” he said.

At the same time, he sees a price to the

progress. “The reason I farm is that I love

being out in the field,” said McAllister.

“It’s why farmers farm, and if you take

that away from me I would probably find

another line of work.”

From his perspective, “sitting in an

office and staring at a computer” holds

little appeal. “Maybe at bigger farms

where they have many pieces of equip-

ment it makes sense. For the average

farm, though, I think producers love being

hands-on with their machinery,” he said.

Of course, bringing such a concept to

market is not without challenges.

“Right now this is just a concept,” said

Bose. “The future depends on customer

interest, state and provincial laws, and the

regulations governing fully autonomous

vehicles.”

One of the main obstacles is that

this technology is often equated with

driverless cars. Bose, however, sees an

important distinction. “We’re not out on a

highway driving at high speeds. We’re in

a fenced field with obstructions that have

been identified and are known year after

year,” he said.

Even though the destination is still a

long way off, Zerby marvels at the journey

thus far that has brought us to the point

where fully autonomous vehicles could be

available to farmers in the not-so-distant

future. “In the past 10 years, we’ve seen

more improvements in production tech-

nology than in the previous 100 years. It’s

hard not to be awed by what lies ahead.”

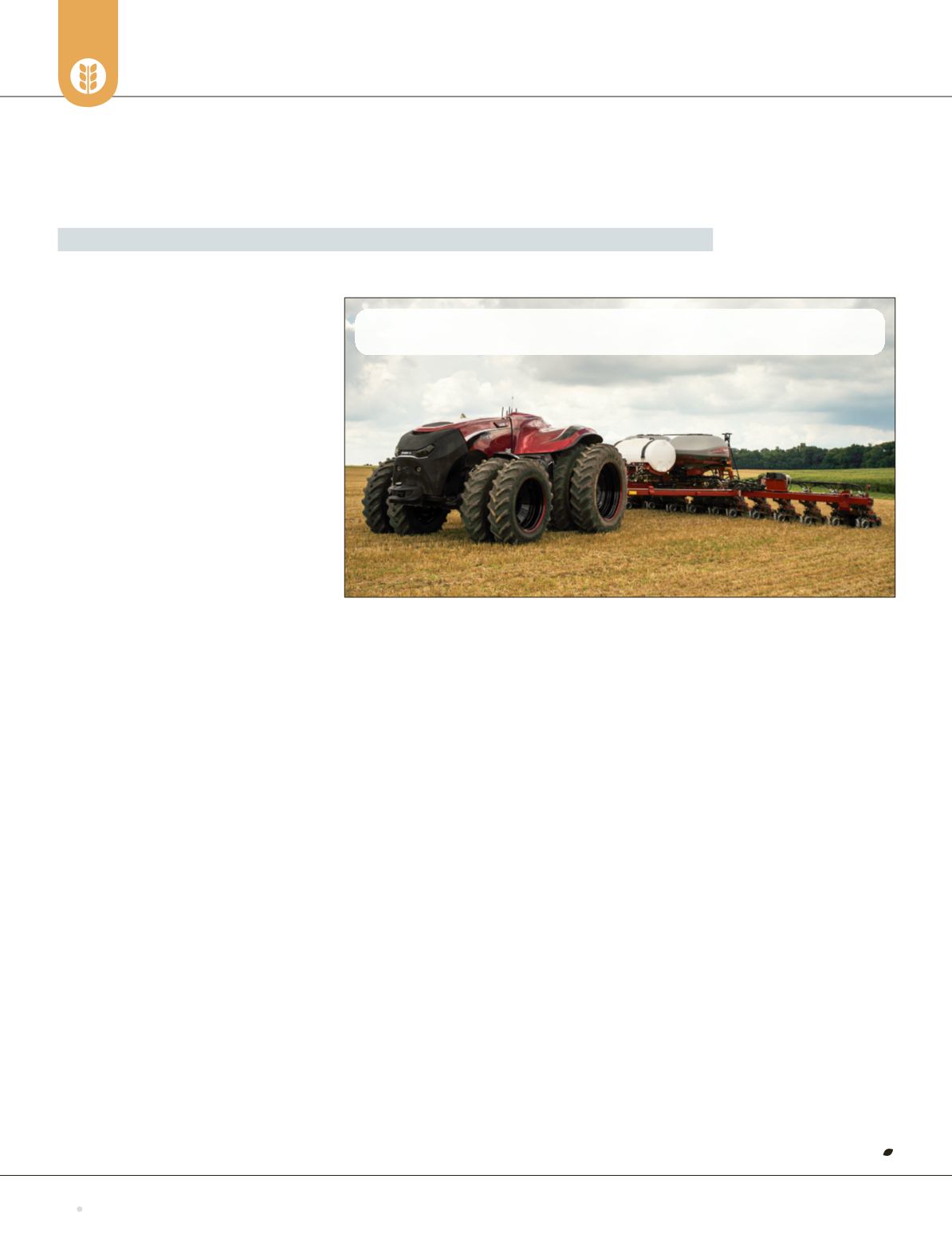

Photo:Case iH

Winter

2017

Grains

West

36

driVerLess traCtors are driVingProgress for ProduCers

FUTURE FOCUS:

Fully autonomous vehicles, like this Case IH tractor prototype, could be

available to western Canadian farmers in the not-so-distant future.