Winter

2017

grainswest.com33

maP reaDing

FHB risk map have been used to help battle

F. graminearum

in

other regions where the fungus has long been an established

problem for farmers. They have been available in Manitoba and

parts of the United States for several years, and the maps were

added to Saskatchewan’s arsenal by the Saskatchewan Wheat

Development Commission (Sask Wheat) two years ago.

“Our board received a strong message from producers

that more resources were needed to help manage FHB,” said

Harvey Brooks, general manager of Sask Wheat.

Identifying areas of the province as high, medium or low

risk, the maps—posted on the Sask Wheat and provincial

government websites—indicate whether weather conditions

are favourable for the development of

F. graminearum

.

“Farmers located in zones with the requisite moisture and

high nighttime temperatures to warrant a ‘high risk’ or ‘medium

risk’ label should be checking their crops and weighing their

management options,” said Brooks. “Plants can’t get infected

until flowering, so if they’re at that stage and conditions are risky,

there is additional material online to guide producers through

critical spraying decisions: whether to spray, which fungicides

are approved for use with

F. graminearum

and the best times to

apply them.”

Although he also advocates use of the maps, Mitchell Japp,

provincial specialist for cereal crops with the Government of

Saskatchewan, agrees with Brooks that farmers should use

multiple resources to determine how they will limit

F. graminearum

infection. “The map is a good starting point to

indicate if there’s risk, but no tool is perfect,” he said.

Japp stressed that farmers still need to be in the field getting

a sense of what’s happening and factoring in local conditions.

“If you are at high risk when the crop head is emerging, which

is when the crop starts to become susceptible, it doesn’t

mean you should spray. Farmers must consider many factors,

including whether they or their neighbours have had FHB

before. They should look at what stage their crops are in, check

the weather, factor in the cost of applying fungicide, estimate

their crop yield and decide if applying fungicide will provide a

positive return on their investment.”

signs of things to come

If you’re worried that a child has chickenpox, you look for spots.

But how do you spot FHB in your crops?

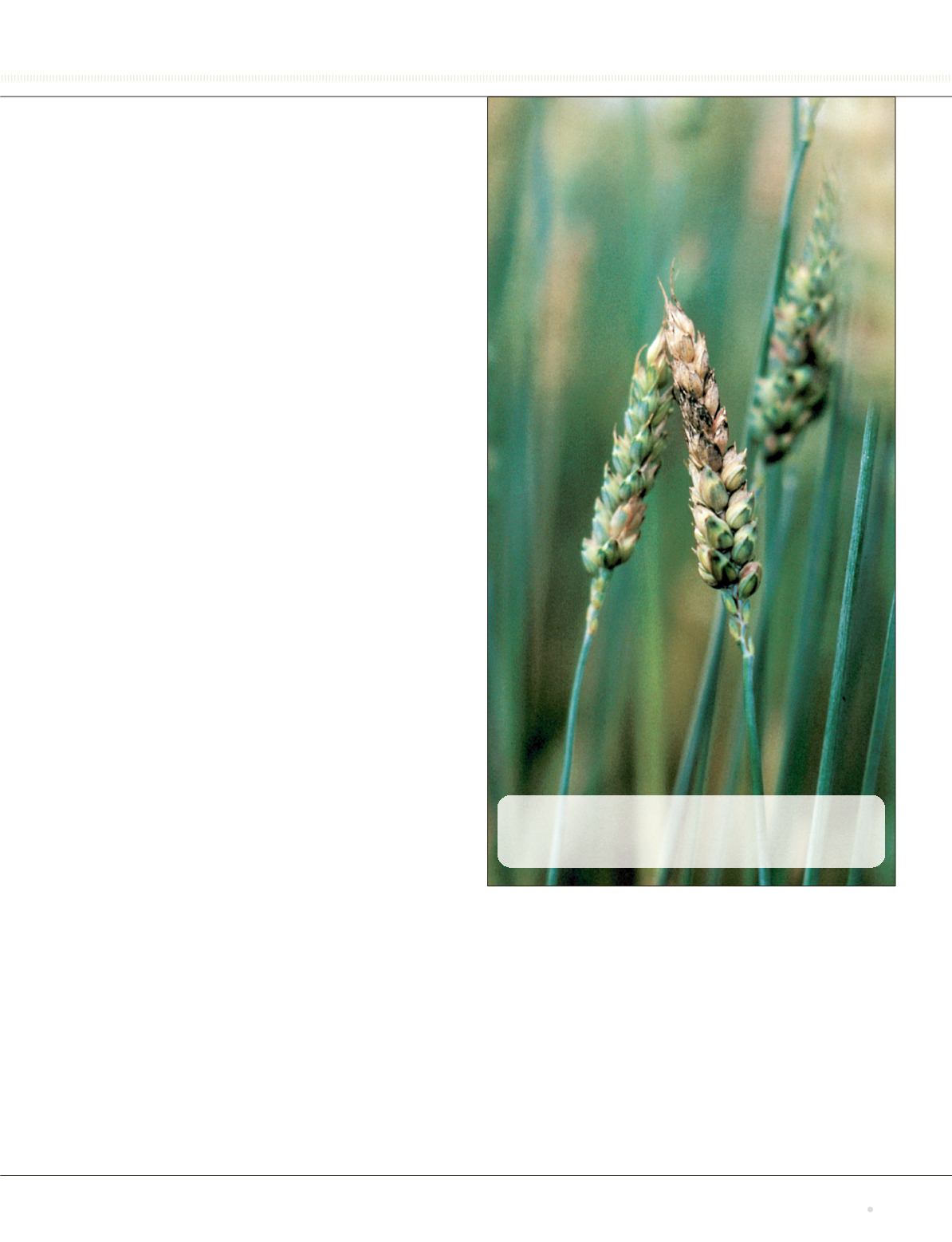

“Symptoms in wheat initially appear as dead, prematurely

ripened portions of the cereal head affecting one or more

spikelets,” said Turkington. “With severe infections, the entire

head may prematurely ripen and there will be a brownish

discolouration of the stem directly below the head.”

Although the symptoms are similar for barley, Turkington said,

“head and kernel symptoms in barley are much less distinct and

can be easily confused with diseases such as spot blotch and

kernel smudge, or even hail damage.”

While knowing what to look for is crucial, knowing when to

look is also important.

“One of the best times to scout for head blight on cereal

crops is at the late milk to soft dough stages, because the

healthy tissues are still green and the infected tissues, which

appear bleached, are clearly seen,” said Michael Harding, a

plant pathology research scientist with Alberta Agriculture and

Forestry.

Bracing for imPact

Turkington warned that it is dangerous to treat Fusarium just

like any other run-of-the-mill cereal disease, given the negative

consequences it can have on producers’ bottom lines.

SPOTTING SYMPTOMS:

Fusarium head blight symptoms in

wheat include premature ripening and brownish discoloration of the

stem below the head, according to Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

plant pathologist Kelly Turkington.