The Food Issue

2016

Grains

West

24

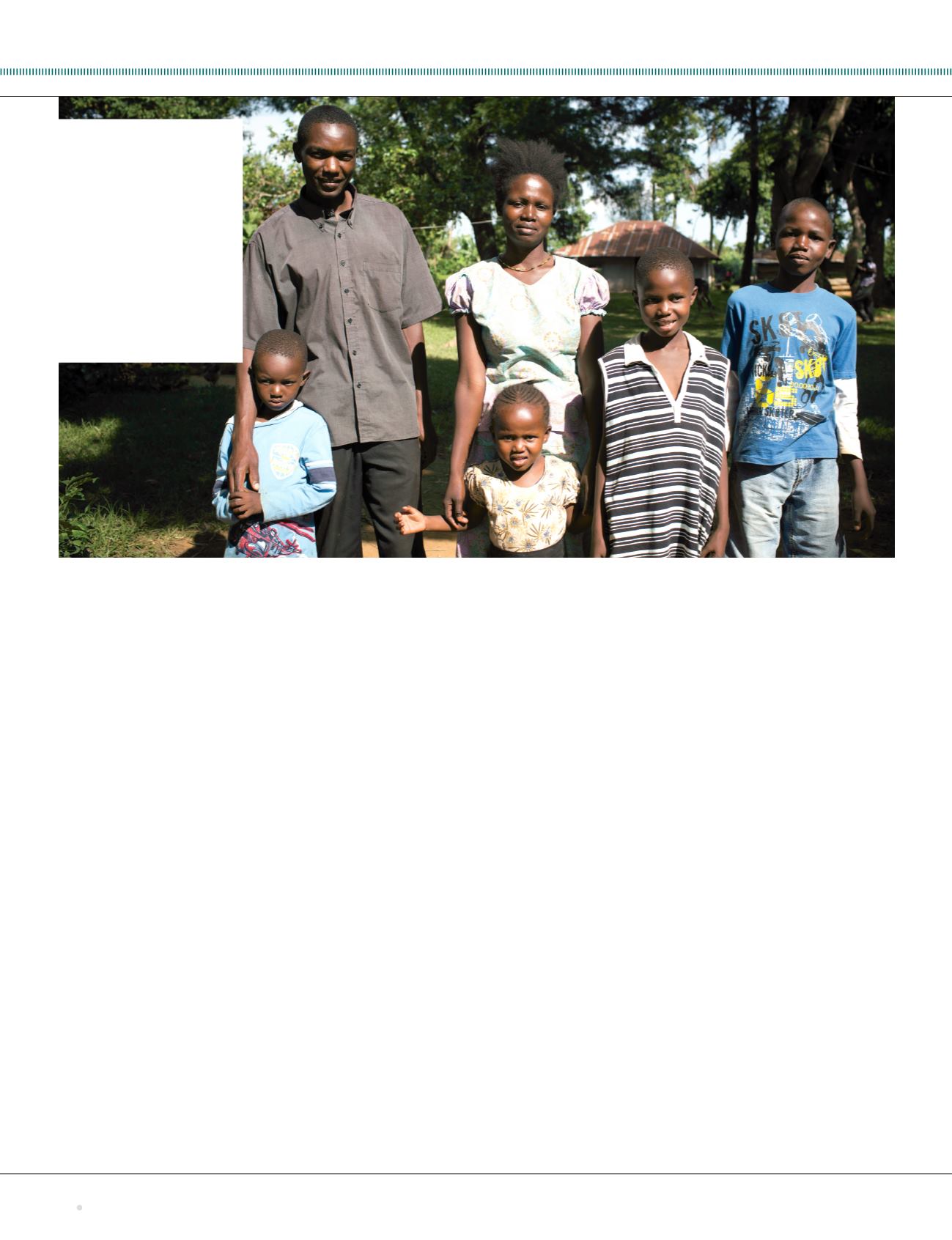

A

lthough it is a country perhaps best

known for its adventure tourism,

Kenya also contributes to one of Africa’s

most important agricultural hubs and is

home to countless small-scale farmers.

Joseph Oloo is one of those farmers.

Along with his wife Angeline Atieno

Sewe and their children, he manages a

two-acre farm in western Kenya, about

500 kilometres from the bustling capital

of Nairobi.

The 37-year-old farmer typically grows

sorghum, maize, groundnuts, soybeans

andmillet. They are the most widely eaten

food crops by most of the families in the

community, according to Oloo. There

are also a handful of livestock roaming his

farmland for manure distribution. From

the time Oloo was in primary school, he

studied agriculture. At one point, he was

a field assistant for the International Plant

Nutrition Institute, a global non-profit

dedicated to managing plant nutrition “for

the benefit of the human family.”

Oloo’s farm has a contoured border

of deciduous silky oak trees that acts as

a windbreak and helps the water table

recharge. “Dropping leaves also form

biomass (organic matter),” he said. In

addition, he fertilizes with compost

manure, which adds nutrients to the

soil and improves its structure for crop

development.

The region’s rains largely dictate Oloo’s

agricultural schedule. Biannual rains

let him knowwhen it is time to begin

planting and harvesting. The first planting

is usually at the end of March or in early

April, followed by a mid-August harvest.

Farmers can then plant again in early

September and harvest a second time in

January. It’s normal to receive 1,500 mm or

more of annual rainfall in the area, which

works great for Oloo’s water-intensive

crops like maize, millet and sorghum.

However, the rain can all fall in a matter of

weeks, making it challenging for plants

to persevere through both excessive

moisture and prolonged dry spells.

For his operation, Oloo’s tools of

the trade represent a vastly different

approach to farming than that of most

Canadian farmers. “I use a jembe

(hoe), panga (machete), planting line,

tape measure and I hire a tractor for

ploughing. Other farm equipment

includes a knapsack sprayer with

herbicides,” he said. “I also do minimum

tillage by spraying herbicides and plant

without disturbing the soil.”

His family helps during planting, and

everyone takes turns weeding and

applying fertilizer. There’s also a slate of

casual workers who weed and harvest

crops.

For Oloo, a successful growing year

is when “the rainfall is adequate and

harvest is bumper … and every home

has enough stock to survive on.”

In 2010, Kenyan citizens voted to

rewrite the country’s constitution,

which paved the way for the national

government’s delegation of powers to

47 largely autonomous counties within

Kenya. For agriculture specifically, this

means that issues can now be examined

at a more hands-on level that recognizes

regional differences.

“The county government bought

tractors, which farmers have (available)

at a subsidized price,” Oloo said, adding

that the county has also sold subsidized

fertilizer and seeds to area farmers.

When Oloo began farming 10 years

ago, profits were much lower.

“The farming pattern has improved

from old method to modern techniques,

improving income and food security,” he

said, adding he earns five times what he

did when he started farming.

Kenya

calling

SMALL-SCALE AGRICULTURE

IS A WAY OF LIFE IN THE EAST

AFRICAN NATION

BY TREVOR BACQUE

Photo: Courtesy of Agrium