The Food Issue

2015

grainswest.com

19

OU’RE CRAVING A COOL DRINK ON A HOT DAY.

You go into your kitchen, turn on the faucet, and there

it is—pure, free-flowing, seemingly endless water. In

any modern home, it’s a convenience so basic we don’t even

think of it as a source of security.

That sense of security, born of a certainty nearly as deep as

the certainty that our next inhalation will pull oxygen into our

lungs, is rooted in the hydrologic cycle—the endless transport

of water around the world, from oceans to mountains to rivers

and back to sea.

On the Canadian Prairies, our water comes from rain, snow

and the vast snow packs of the Rockies. Water evaporated

from the oceans falls on mountaintops, where it freezes in

winter, then melts in the spring and summer, cascading down

the rough hillsides to collect in streams that merge into rivers.

In these rivers, it flows out across the land, cleaned by riparian

areas rich in plant and animal life. Municipalities divert some

of it, treating it and delivering it through an immense system of

pipes to your home.

After you’re finished with it, the water leaves your home

through an equally immense waste system to treatment

facilities where it is cleaned. From there, it is returned to the

rivers, where it rejoins the flow to the oceans—which ocean

depends on where you live. If you’re an Edmontonian, your

water comes from the North Saskatchewan River and returns

to Hudson’s Bay. In similar fashion, if you live in Calgary,

drawing your next drink from the Bow River, the water leaving

your home also returns to the Hudson.

Many water experts think that our faith in the endlessness

of that cycle, its invariance, is misplaced. Robert Sandford,

Epcor water security research chair at the United Nations

University, has been thinking a lot about the mistakes that

sense of security leads to: “We are beginning to realize that

we have accepted and encouraged wasteful water use as

a social norm. We have, at enormous cost, overbuilt water

infrastructure to support that wasteful norm. Now we find

we cannot afford to maintain and replace the entire overbuilt

infrastructure that supports that waste, which increases the

risk of public health disasters like [the E. coli outbreak in]

Walkerton [Ontario].”

That complacency and sense of security, and the wasteful

choices it has led to, will soon require us to rethink how we

manage our most precious resource. As we look ahead to

the rest of the 21st century, we can start to see the shape of a

long-lasting disruption coming—a change in the whole water

cycle itself. To begin to understand what that would mean in

the future, it’s important to understand how we currently use

water in Alberta.

OIL AND WATER

Urban users are allocated roughly 11 per cent of Alberta’s

water resources for their homes, lawns, gardens and pools.

Many would guess that the province’s famous (even infamous)

oil and gas industry uses much of the rest. To free up the 168

billion barrels of extractable oil in northern Alberta, the third-

largest reserves in the world, takes roughly three barrels of

water for each barrel of oil produced. Water is used to boil the

sand, allowing the heavy bitumen to rise to the top; to cool the

massive machinery; and to make hydrogen and oxygen for a

range of other industrial chemical uses. However, the oil and

gas industry accounts for only about six per cent of the annual

water allocation in the province.

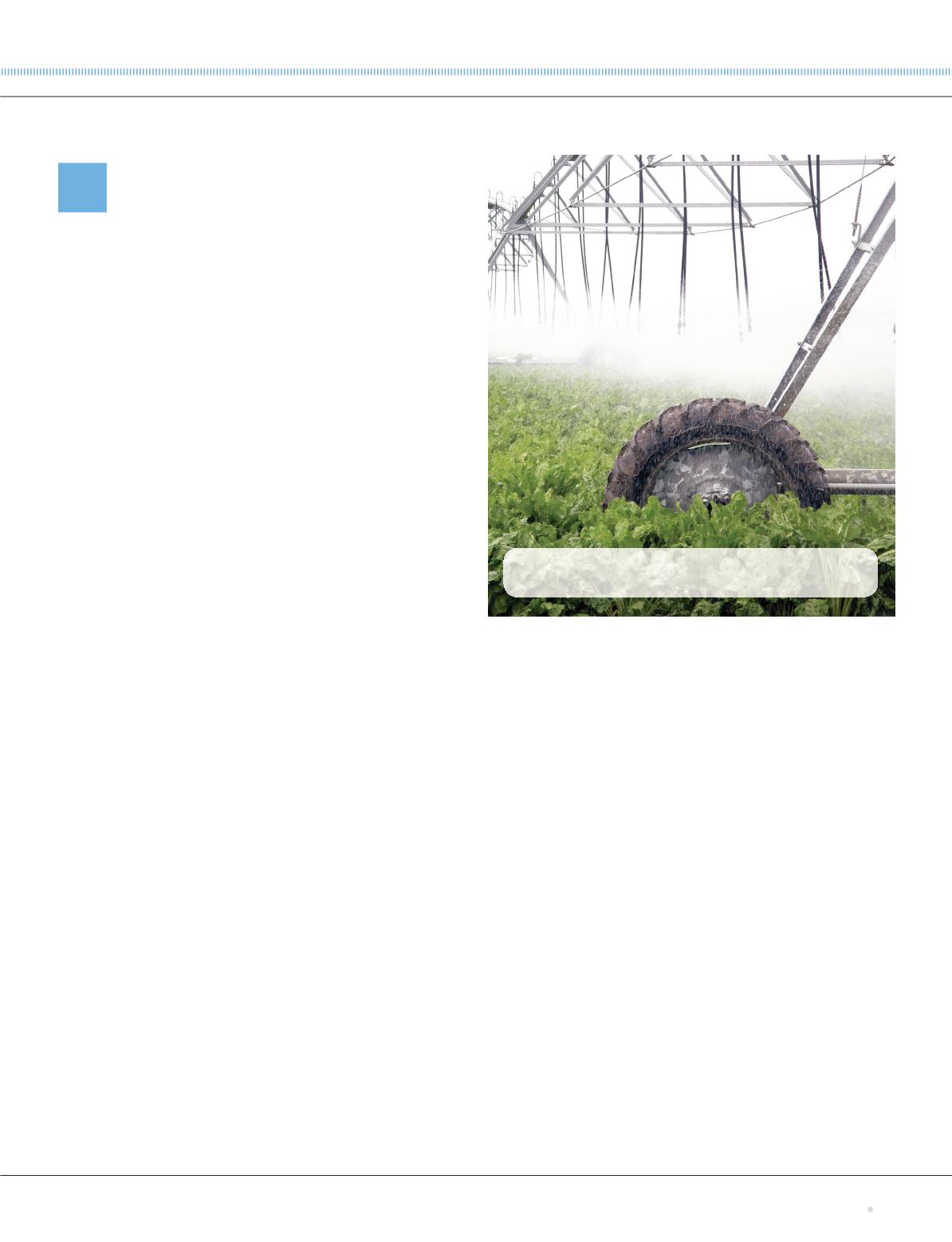

The majority of Alberta’s water—60 to 65 per cent of all

water consumed in the province on average—is used to

irrigate more than 625,000 hectares of agricultural land.

Irrigation is vital to agriculture in many areas and Alberta is

an irrigation powerhouse, encompassing 65 per cent of

Canada’s irrigated land area. Irrigation is also tremendously

productive—while less than six per cent of cultivated land in

the province is irrigated, nearly 20 per cent of Alberta’s gross

agricultural production comes from irrigated land.

Growing crops on irrigated land takes enormous volumes

of clean water. To visualize just how much, picture all the

water needed in a season pooled on the land. The water to

grow spring wheat would be 42-48 centimetres deep, canola

40-48 centimetres deep and potatoes 40-55 centimetres

deep. Imagine that depth of water stretched over the

province’s irrigated land and you can begin to grasp just how

much water needs to be available throughout the year.

Y

Irrigation, which accounts for the majority of the province’s

overall water use, is vital for farmers in southern Alberta.