Spring

2018

Grains

West

32

to the guidelines listed in the Act,” he

continued. “There are other options, they

just can’t sell it as seed.”

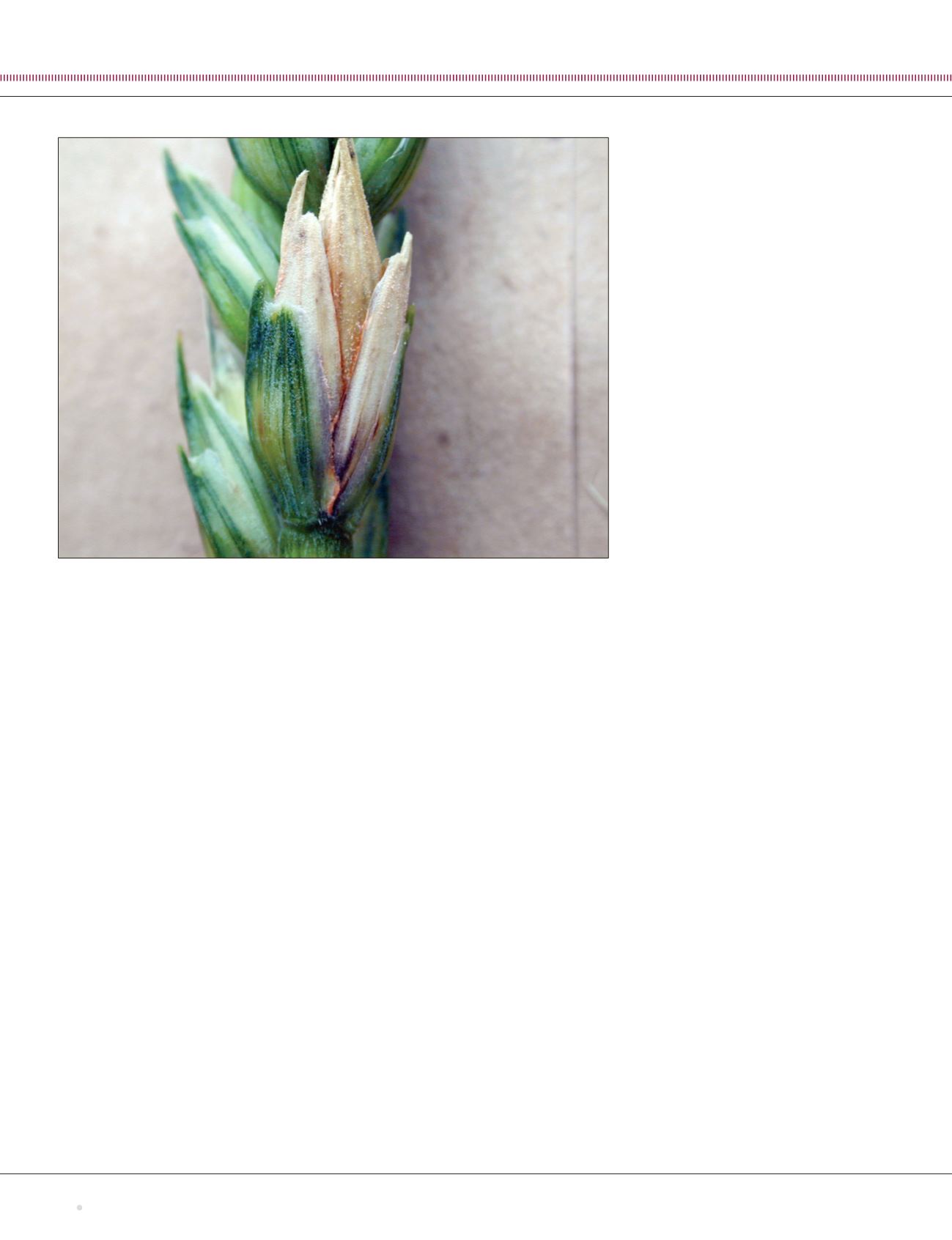

As it becomes more common on

the Prairies, Fusarium has created

problems for farmers, including yield

loss, downgrading issues and market

acceptability issues when mycotoxin

concentrations are high—and Alberta

seed producers are particularly hard hit.

In Alberta, FHB has most commonly

been found—and done the greatest

damage—in the southern part of the

province, said Harding. “But in 2010, the

information we were getting from the

seed testing labs and from the Canadian

Grain Commission was indicating that

it was becoming more common than

it previously had been in areas outside

southern Alberta,” he said.

In 2015 and 2016, Alberta Agriculture

and Forestry (AF) conducted a survey

that determined FHB levels were quite

high in a number of counties outside

southern Alberta. Those areas, including

along the Saskatchewan border as

far north as Lloydminster, now have

significant levels. “It looks as though

Fusarium either is becoming, or has

become, well established along the

eastern border,” said Harding.

Given that FHB doesn’t simply go

away once established, some farmers

believe a near-zero-tolerance policy no

longer makes sense. “If you’re in an area

where it’s really common, it really doesn’t

make any difference if there’s a little bit

of Fusarium on the seed because it’s

already established in the crop residue at

a level much higher than it would be on

the seed,” said Harding. But, he added,

“We want to prevent it from spreading.”

For Greg Stamp, whose 5,500-acre

seed growing operation is located near

Enchant in southern Alberta, FHB can be

an issue. He says 2016 was a particularly

tough year, especially for durum, and

that it’s difficult to get certain varieties

into the province because of low-level

FHB. “Some varieties aren’t accessible

in Alberta, period, the way the rules are

set up,” he said. “So, that puts Alberta

behind a little bit.

“Some of the companies that want

to grow high-generation seed here,

maybe they’re scared to because if it has

half a per cent Fusarium, then they can’t

use it even though that number is quite

manageable,” he said.

On the plus side, a bad FHB year can

also generate interest in other provinces

for Alberta-grown seed. “In 2016, we

had farmers looking for durum,” said

Stamp. “Some farmers in Saskatchewan

were just happy to get something that

had lower disease levels and better

germination.”

MANAGING FUSARIUM

To avoid yield loss, prevention is key,

said Kelly Turkington, Agriculture and

Agri-Food Canada research scientist.

Growers who are concerned about

Fusarium in 2018 should look at how

their crop did in 2017, said Turkington.

Was it downgraded? Did tested seed

come back positive? “That will give them

some indication of what could potentially

happen,” he said.

For those who live in regions where

typical rotations are canola-wheat-

canola-wheat, this year may present

an issue. Those who were in wheat in

2016 when FHB hit a record-high level

might consider skipping wheat this year.

“That residue from 2016 would still be

in the field and could contribute spores

that could infect their 2018 crop,” said

Turkington, who also advises farmers

to determine if their neighbours have

FHB problems. “If you’re looking to

plant a cereal crop, and adjacent fields

have been in corn for a while, there’s an

elevated risk,” he said.

He also emphasized fungicide

timing as an important factor that

determines impact. “If you’re looking

at using a fungicide, the problem is

that you have to make the decision to

spray before you actually see disease

symptoms in the crop,” said Turkington.

“If your weather maps are indicating

that you’re at moderate to high risk,

and your previous history with the

issue has it well established in your

fields or neighbouring fields, in that

situation, spraying might improve grade

and could mean a sizable economic

benefit.”

The prevalence of Fusarium head blight on the Prairies and its increasing occurrence in Alberta has farmers

questioning the province’s zero-tolerance policy.