Spring

2016

grainswest.com

13

ples are graded at accredited grain grading

labs. Often, growers will get both Canadian

and U.S. grades on the same sample. With

information in hand, growers can now

shop their grain around to end users, to

grain companies or to brokers in order to

extract the most value.

Buyers who are buying on specification

are generally looking to have some addi-

tional assurances around falling number,

vomitoxin levels, protein and moisture.

“Buyers do buy on spec, but it still has to

be relatively easily and quickly measure-

able,” said Doug Hilderman, director of

western grain for Broadgrain Commodi-

ties Inc. Other contracts, like identity-pre-

served contracts, might have even more

stringent requirements for quality, but,

generally, the price the farmer receives

reflects this higher standard.

However, not all grain can or will

be bought on specification. “It doesn’t

take much imagination to understand

just how di cult it would be to load a

60,000-tonne vessel at port if it all had to

be purchased on specification,” Driedger

said. “Quite simply, a big chunk of the

grain has to move that way just to get the

crop sold in time for next harvest.”

Buyers of Canadian grain are most

interested in purchasing grain that meets

the specific demands of their custom-

ers. Those demands might be met with

grades, but, more often than not, more

detail is needed—buying on specification

is common. Some buyers (or end users)

are a lot more particular than others, it

depends on what they are manufacturing.

Growers who understand this and can

reliably provide information about their

own production, and then deliver what

they promise, are the ones who receive

premiums in the market.

Grades di er north and south of the bor-

der. Mildew is a good example of a factor

in play for the 2015 crop. Canada grades

mildew tougher than in the United States.

“This year, mildew is the primary reason

for downgrading in Western Canada,”

said Elaine Sopiwnyk, director of grain

quality at Cigi. “It’s an aesthetic factor that

doesn’t a ect food safety or functionality,

but it can negatively impact flour colour.”

Flour colour has an impact on end-product

quality and consumer acceptability. Grain

with mildew will not work for consumers

who want white pan bread with a bright

crumb colour or Asian noodles with high

levels of brightness. Additionally, it can

cause increased speckiness in pasta made

from semolina milled from Canada West-

ern Amber Durum. In the United States,

mildew is not considered a downgrading

factor in the same way, so a Canadian

grower might find better value for his

grain south of the border.

This year, more of the wheat crop grad-

ed a No. 1 or No. 2 than the year prior.

“Durum is a good example,” Sopiwnyk

said. “In 2014, only 13 per cent of the crop

graded a No. 1 or No. 2. This year, 50 to

60 per cent was in the top two grades.”

This in turn will reflect in the spreads

between grades. “It’s important to under-

stand that the grade tolerances for the top

two grades for, say, CWRS are kept very

tight to maintain the functional quality

of the grain. The grade tolerances for the

various degrading factors don’t change

year over year unless research supports

such a change. When you get to a No. 3,

that’s when the tolerances open up and

there is the potential for greater impact on

functionality.”

This year, the crop is performing very

well. “The data is showing little in the way

of di erences in the performance of No. 1

to No. 3 CWRS,” Sopiwnyk said. “Howev-

er, this data doesn’t tell the whole story.

We are seeing impacts in the flour and

the rheological properties of the dough.

For instance, we are seeing a decrease in

gluten strength in No. 3s, compared to

No. 1 and No. 2, which has caused some

challenges in baking.” Additionally, Sopi-

wnyk said that No. 3 CWRS showed lower

specific volume in the pilot baking process

and poorer colour in Asian noodles—al-

though the poor noodle colour was a

reflection of mildew, not gluten strength.

It’s not strictly a quality scenario that

will determine price, however. Supply

and demand plays a large part in that

determination. “Right now, we are seeing

the CWRS spread from a No. 1 to a No.

2 at roughly five to 10 cents, compared

to closer to 20 cents in recent years,”

Driedger said. “The spread from a No.

2 to a No. 3 is wider, ranging from 25 to

50 cents, compared to 60-plus cents in

recent years. That spread will improve

when the elevator is specifically trying

to source a No. 3 CWRS.” For this year,

the narrower spreads could be reflective

of the closer performance of the top

two grades. These spreads, and prices in

general, vary depending on catchment,

company, general demand and demand

on any particular day.

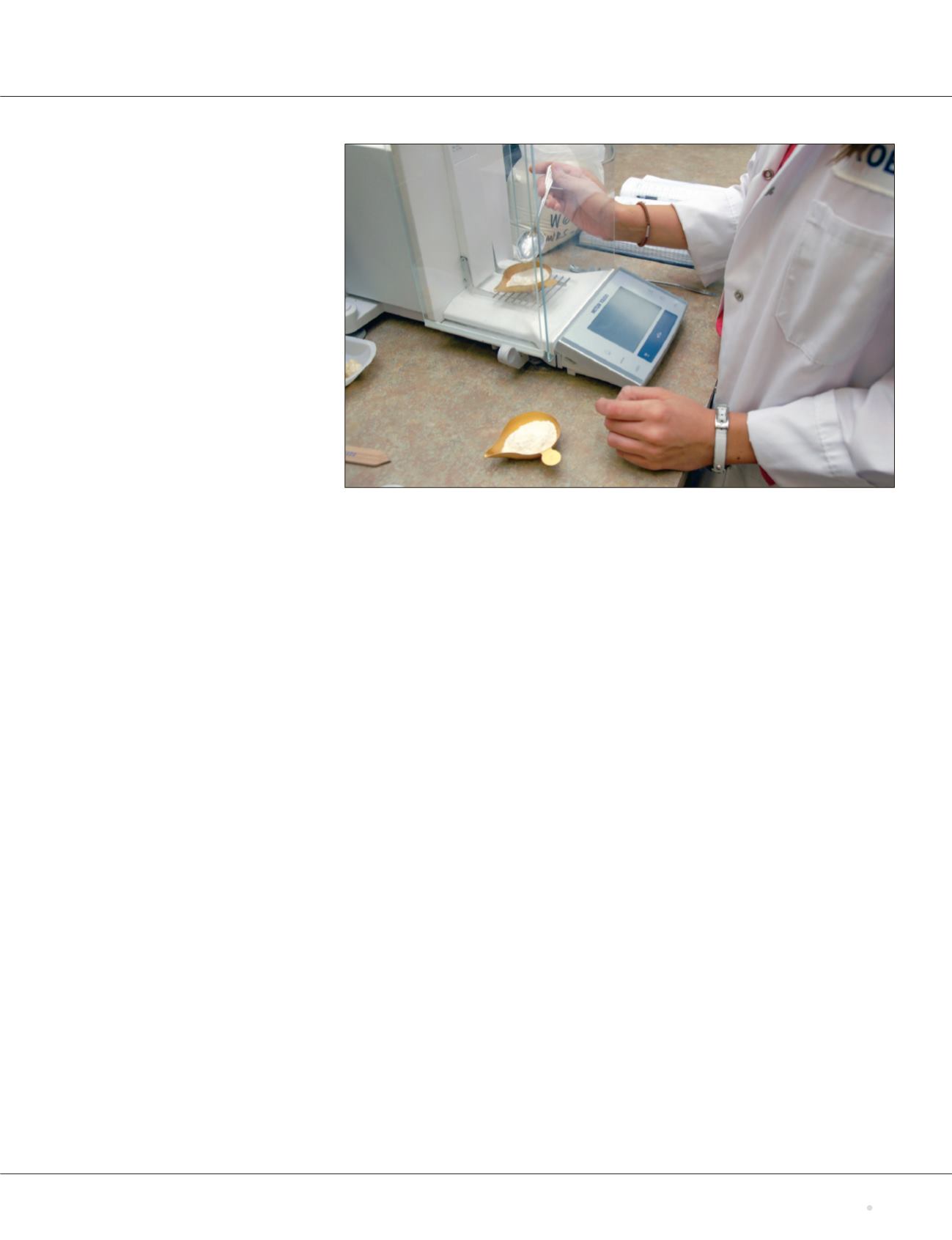

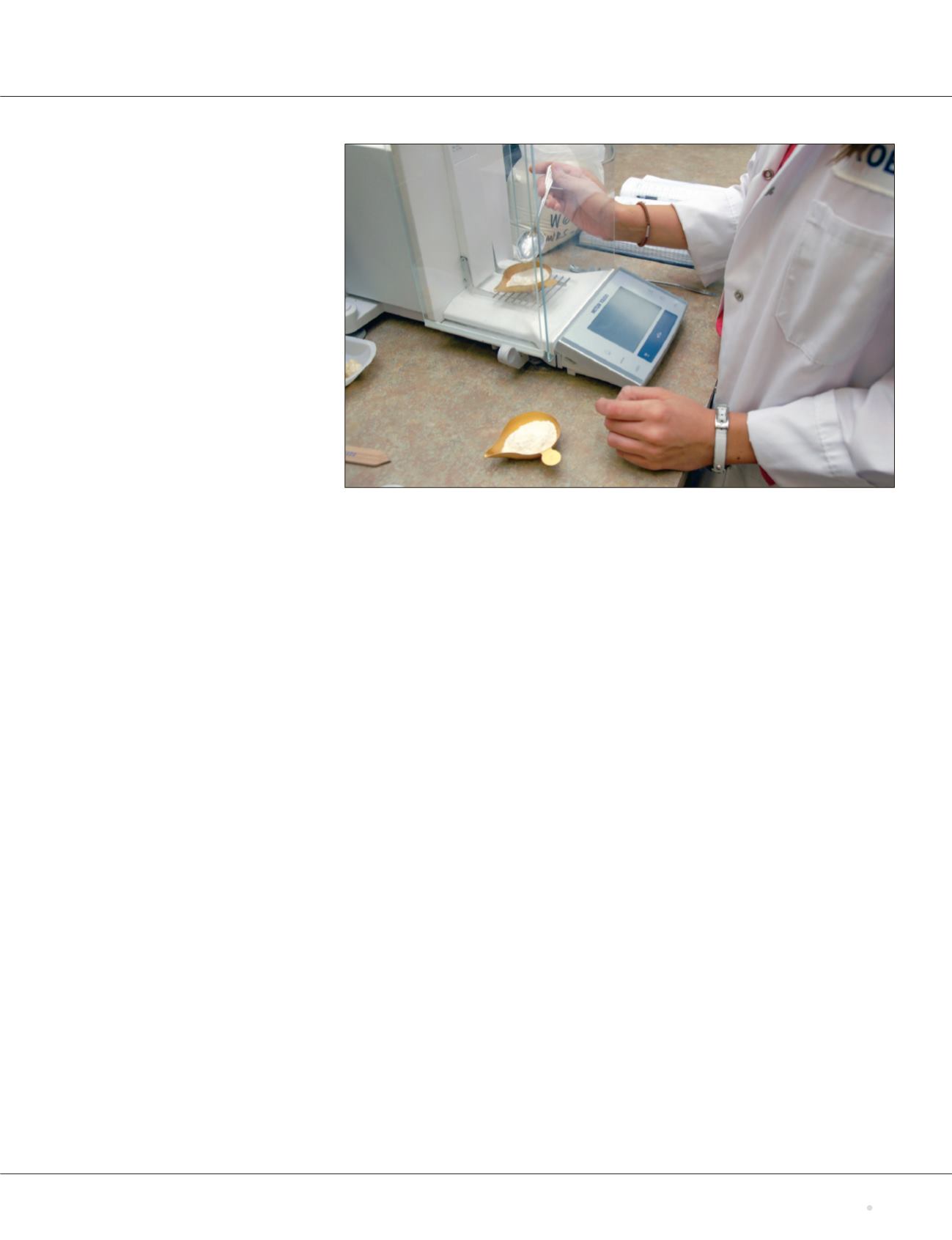

RobynMakowski, analytical services technician, weighs samples for falling number testing at Cigi.

Photo: Canadian InternationalGrains Institute