Basic HTML Version

relations and grocery division at the Retail

Council of Canada.

“What we have right now is a very,

very informed and educated consumer,”

he said. “They are looking to make

choices for their families that meet their

unique needs.

“You just have to walk through the

aisles to see the expanding variety of

labels,” he added. “They wouldn’t be on

the shelf if they weren’t of interest to the

consumer.”

To get a grip on the proliferation of

new food labels and product claims,

the federal government announced the

Food Labelling Modernization Initiative

in the 2013 Speech From the Throne.

This work is being undertaken by

Health Canada and the Canadian Food

Inspection Agency (CFIA), which share

responsibility for food labelling.

Gary Holub, a spokesperson for

Health Canada, said an initial round

of consultations with consumers and

producers began in January and was

completed in April.

“Over the past few months,

Health Minister Rona Ambrose and

her colleagues have hosted round

table discussions across the country

and provided all Canadians with an

opportunity to provide feedback directly

to Health Canada by filling out an online

questionnaire,” he said.

Holub did not say when the new

regulations are expected to come

into force.

Core food labelling requirements

in Canada are quite simple. As a

baseline, all foods—with the exception

of products like raw fruits and

vegetables—must have a label. This

must include the food’s common name,

expiration date, net quantity, a list of

ingredients and the familiar nutritional

information box. Beyond this, it must

be bilingual, include the name and

address of the manufacturer, and list any

allergens contained.

Nutrition claims such as “cholesterol-

free” and “reduced in calories” are also

permitted, as are certain limited health

claims such as “a healthy diet low in

saturated and trans fats may reduce the

risk of heart disease.”

Voluntary labelling not related to the

safety of the product, on the other hand,

is a bit of a mixed bag. Used primarily

for marketing purposes, these voluntary

claims range from highly regulated to

virtually meaningless.

Laura Gomez is an Ottawa-based

lawyer with Gowlings, and specializes

in food labelling. She said that there are

pages and pages of regulations behind

some product claims, but relatively little

for others.

“Consumers really want to have

clear labelling and they want it to be

true,” she said. “But consumers may

not necessarily understand what the

regulations are, so there is potential for

some confusion.”

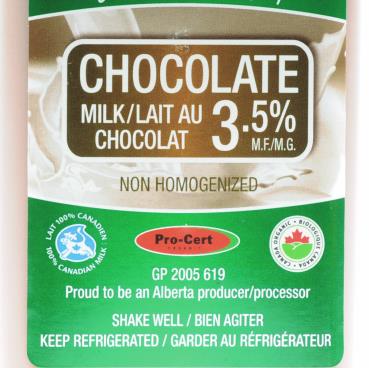

On the heavily regulated end of the

spectrum are certified organic claims.

According to Gomez, organic producers

are frequently audited by government-

certified inspectors who check every

step of the product process to ensure

no synthetic fertilizers, pesticides or

other substances are used. Only then

are products found to have greater than

95 per cent organic content allowed to

use the “Canada Organic” logo, which

increasing numbers of consumers look

for. Should a producer fail to meet the

stringent Canada Organic Regime

standard, it is delisted and must stop

making organic claims.

The tight regulatory oversight for

organics is a major contributor to the high

costs of these products, Gomez said.

“When you are adding more

information to a food label that requires

certifying information through the food

supply chain, that will likely increase the

cost of manufacturing that product.”

Labelling claims are now extending to

genetically modified organisms (GMO),

as well. To see products branded “non-

GMO” or “GMO free” is becoming

increasingly common, with even

stalwart brands like Cheerios adopting

a voluntary non-GMO label, meaning

the cereal doesn’t contain genetically

modified organisms.

Canada currently has a voluntary

labelling scheme for foods that are not

products of biotechnology or genetic

engineering, but parts of the United

States are moving aggressively towards

mandatory GMO labelling. In early May,

the Vermont senate passed a law to enact

mandatory labelling of GMOs, making

it the third U.S. state to pass such a law

after Maine and Connecticut.

Cathleen Enright is executive vice-

president for food and agriculture at the

Biotechnology Industry Organization,

an American pro-GMO lobby group.

She said mandatory GMO labelling will

require extensive product re-labelling,

and some major brands may reconsider

selling their products in these states,

given the high cost of changing labels for

a relatively small market.

Enright said companies are searching

for ways to defray the costs of expensive

voluntary labelling. Major cereal producer

Post, for example, recently made Grape-

Nuts GMO-free but reduced package

contents from 32 to 29 ounces while

keeping the price per box the same.

Enright said there is an ongoing push

from the American industry for national

regulations on GMO labelling, to keep

costs down and labelling consistent from

state to state.

The Food Issue

2014

grainswest.com

19