The Food Issue

2017

Grains

West

26

He gathered Marquis and a number of

other crosses as he began to investigate

their utility. There was only one problem:

it was winter and he had no lab for

chemistry, no mill for flour production

and no oven for baking. So, Charles

improvised. According to historian

Stephan Symko, “… he would take a

few grains from each stalk, chew them

and decide on their probable flour and

bread quality on the basis of the dough

created in his mouth.” Charles himself

said of the process, “I made more wheat

into gum than was made by all the boys

in any dozen rural schools.” He figured if

his teeth could substitute for a mill and his

mouth for an oven, he’d get results soon

enough, wrote Symko.

Charles must have had an educated

palate because Marquis was put forth as

Charles’ top choice of wheat following

his oral investigation. His work gained

such importance that he was eventually

knighted and given a $5,000 annual

pension from the Canadian government

in his later years.

By 1907, as Marquis seed samples

proliferated, they were sent to Indian

Head, SK, for further tests and

propagation. From Indian Head they

were sent to Brandon, MB, in 1908,

before being made public to farmers in

1909. Marquis had a trifecta of qualities

that made it superior to Red Fife: early

maturity, high yield and strong straw that

kept the crop from lodging (when a crop

falls over in the field, reducing quality and

complicating the harvesting process).

Farmers were ecstatic and so were grain

buyers, millers, bakers and customers.

In 1914, Marquis migrated south

to the United States. It only took one

growing season for Yankee farmers to be

converted. When the Great War ended

in 1918, more than 20 million acres of

Marquis were grown in North America.

The crop value of Marquis in Canada

alone in 1918 was US$259 million.

Combined with the four major crop-

producing American states of Montana,

the Dakotas and Minnesota, Marquis’

total crop value was US$629 million.

Marquis dominated the landscape

in Canada and grain-heavy American

states for more than 30 years following

the First World War. Even though it was

the Canadian government that received

credit for its Marquis, Charles said it was

“God Almighty” who was responsible for

the variety’s success.

Americans took note of Charles’

unheralded contributions to agriculture,

as well. “The greatest single advance in

wheat ever made by the United States

was the introduction of that class of hard

spring wheat known as Marquis wheat.

The idea came to us free of charge from

the Dominion of Canada’s Cerealist, Sir

Charles E. Saunders,” said James Boyle,

former U.S. secretary of agriculture.

THE NEXT GENERATION

In 1918, 14 million acres of spring wheat

were planted on the Prairies, with

Saskatchewan accounting for 9.1 million of

those acres. However, the need for new

varieties continued in theWest. Eventually,

Marquis’ reign came to an end, as farmers

had to work harder to prevent diseases

and abiotic stresses, such as wind, rain,

hail and snow, fromdestroying their farms.

SinceMarquis was a quintessentially

Canadian invention, it was the United

States’ time to return the favour.

University of Minnesota wheat

breeders eventually created a spring

wheat variety called “Thatcher” in 1935.

It was very similar to Marquis, but had

greater fungal resistance and matured

even earlier. Slowly but surely, Canadian

acres seeded to Marquis were converted

to the new variety. But in 1953 alone, 3.5

million acres of cropland were lost due to

disease pressure. A newwheat line called

“Selkirk” was released as an immediate

response, which managed to reduce

incidences of disease in the short term.

A short-lived but high-performing

variety named “Manitou” appeared

in 1965 for a few years before it

was overshadowed by the next big

breakthrough in 1969. Developed

inWinnipeg, “Neepawa” had all the

trappings of a winner: high yield, high

protein, strong disease resistance and

wide uptake by Prairie farmers. In fact,

Neepawa made history in 1980 when it

was declared that it had replacedMarquis

as the new standard against which all

other wheats would be measured. It was

the second time in Canada’s history a

wheat variety surpassed an established

line in terms of all-around quality.

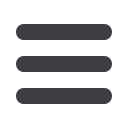

A field of Marquis wheat at the Central Experimental Farm in Ottawa. It was at this farm that Sir Charles Saunders

discovered the famed variety.

Photo:LibraryandArchivesCanada