BY CLARE STANFIELD

GETTING A HANDLE ON THE

SITUATION

While certain wheat varieties have some

tolerance to FHB, there is only one with

full resistance, Canterra’s AC Emerson,

so producers must manage for the dis-

ease in order to meet quality standards.

And those standards are high, because

deoxynivalenol (DON), the mycotoxin

produced by FHB, is harmful to human

and animal health, and can render a crop

unsellable.

“Customers are expecting a certain

quality in our grain,” said Daryl Be-

switherick, program manager, quality

assurance standards and reinspection,

for the Canadian Grain Commission in

Winnipeg. “All shipments of grain leaving

Canada must be inspected by the Grain

Commission so we can ensure the shipper

is getting what they’ve agreed to buy.”

Canada’s official grading guide sets out

FHB limits for all classes of wheat and

cereal grains, and they are low. In Canada

Western Red Spring, for example, which

accounts for over half of the wheat grown

in Canada, No. 1 can have no more than

0.25 per cent Fusarium-damaged kernels.

No. 2 is 0.8 per cent, and No. 3 is 1.5 per

cent. In malting barley of all stripes, it’s

even lower at 0.2 per cent.

Beswitherick said that the average FHB

level in Canadian shipments has remained

relatively stable over the last few years.

“It hasn’t grown by leaps and bounds,”

he said. “But it does fluctuate from year

to year, and we are seeing it move west.

Farmers in Alberta should definitely try

to keep it out if they can—if you talk to

Manitoban producers, a lot of their grain

is downgraded because of FHB.”

The results of Harding’s survey will help

Alberta growers get a clearer picture of

the state of FHB in the province. It builds

on earlier surveys done in 2001-03, 2005

and 2010-11.

The new survey is extensive. Ag field-

men and Alberta Agriculture and Forestry

staff will randomly select 900 fields across

all cereal-growing regions and take 500

heads from each one. The heads will then

be dried, threshed and sent to the Canadi-

an Grain Commission to be tested. “The

lab tests will determine the Fusarium

strain, if there is one, and the amount of

toxin,” said Harding.

He said that past surveys have revealed

a pattern. “

Fusarium graminearum

is easy

to find on wheat and corn in the irrigated

areas of southern Alberta. That’s not to say

it’s wall to wall, but generally speaking, it’s

well-established there,” he said. “North of

[Highway 1], it’s more difficult to find. So

it’s there, but [it] may not be permanently

established just yet.”

But lab tests reveal a troubling change

in the pathogen itself. Harding explained

that, as with any biological organism,

Fusarium graminearum

is subtly adapting

by developing a new chemotype—one that

is a more aggressive pathogen and pro-

duces a higher level of DON. “One of the

biggest reasons this survey is so important

is to track these types of changes,” he said.

Of the current survey, Harding said

he doesn’t expect to see much change

in southern Alberta. “But we’ve been

hearing that seed-testing labs are finding

higher levels of seed-borne

Fusarium

graminearum

in other parts of the prov-

ince as well,” he said. “We don’t know yet

if that means it’s becoming more com-

mon elsewhere, but it wouldn’t come as

a terribly big surprise, because the path-

ogen is certainly capable of expanding

to all cereal-producing areas of Alberta.

We would like to prevent that, or slow it

down as best we can.”

How? Most producers already know the

basics—not planting infected seed, using

certified seed when possible, and mini-

mizing the movement of infected seed and

straw. Harding said Alberta’s

Fusarium

graminearum

management plan is a good

place for anyone to start.

Larocque said that his positive DNA tests

have increased vigilance on his farm and

those of many of his clients. “We’re doing

a few more acres of split fungicide applica-

tions,” he said, adding that this is a precau-

tionary measure, done without evidence of

disease being present. “That shift has taken

place with the innovative guys—the pro-

ducers who aren’t worried about spending a

bit more to protect their crop.”

He’s keeping a closer eye on the

weather too, as historical rain patterns

change. “Moisture leading up to and

during flowering is cause for concern,”

he said. “And the one thing we all need

to get right is residue management and

seeding for strong emergence and even

crop development.”

“We’ve seen this disease move through

Manitoba so quickly there really wasn’t

anything anyone could do about it,” said

Harding. “But, because it’s moving more

slowly here, producers have the time to act

and react. They will do what they need to

in order to protect their grain.”

Fall

2015

grainswest.com

49

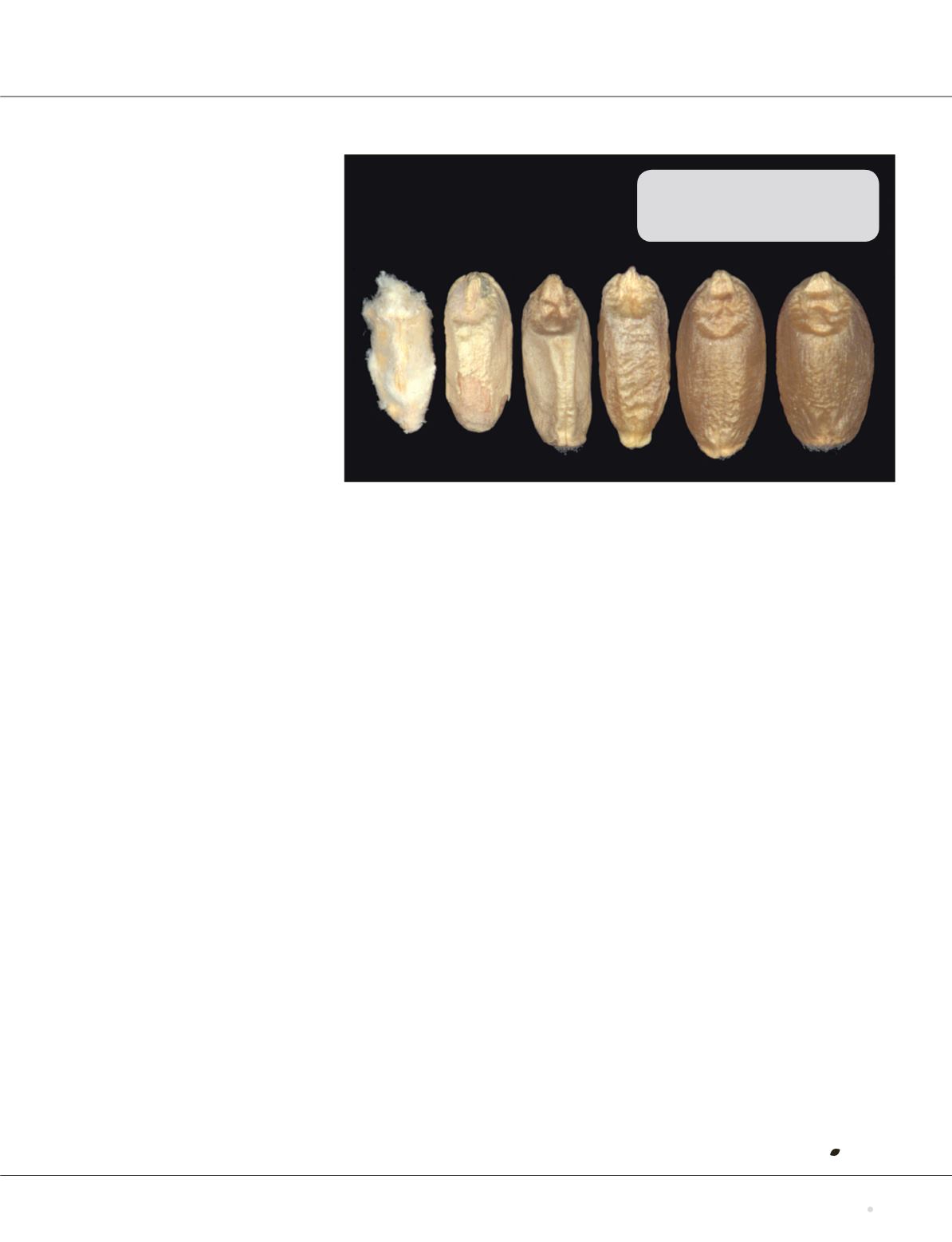

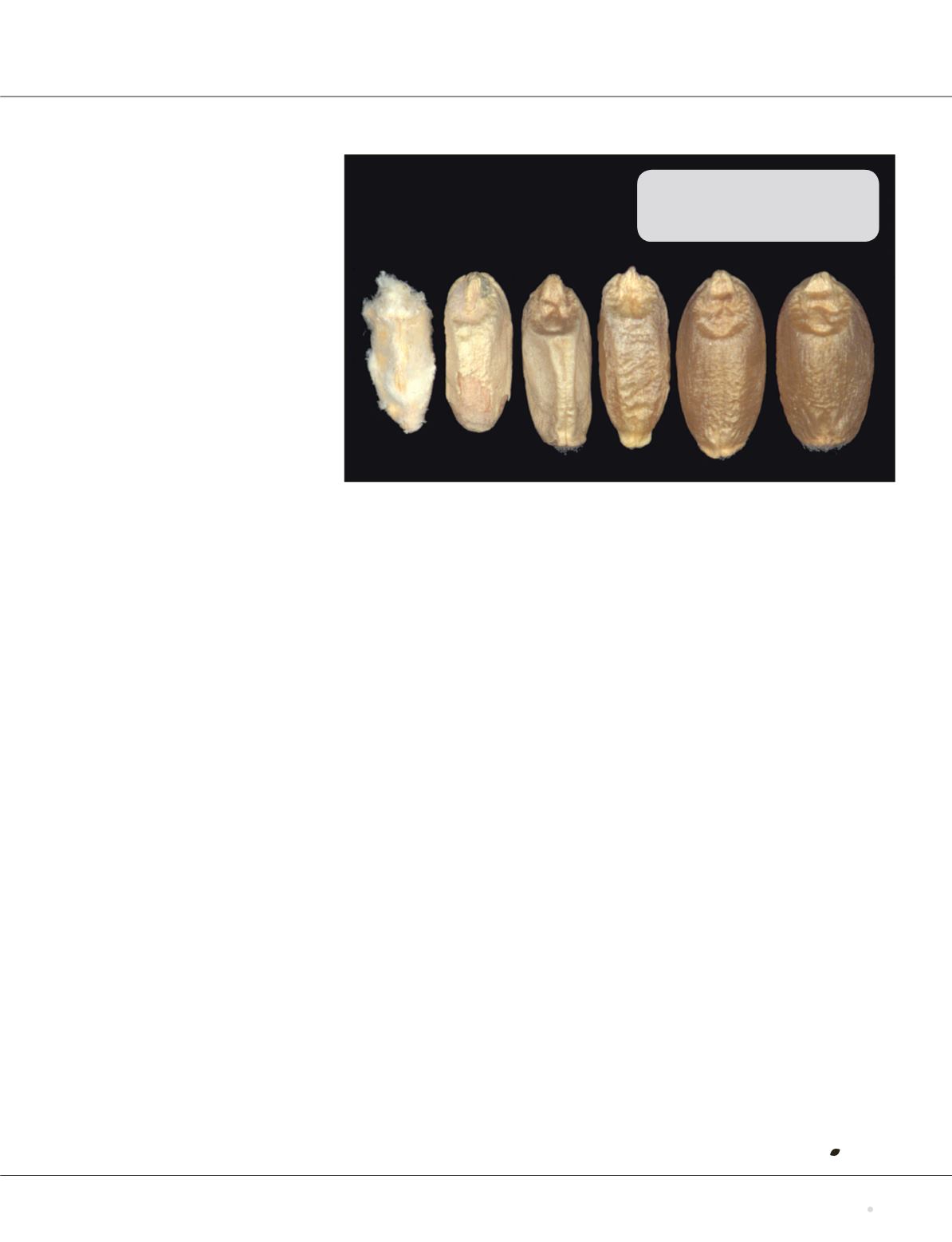

WASTED POTENTIAL:

Fusarium can

cause yield losses, grain downgrading and

market rejection of infected grain.

Photo: Canadian Grain Commission