THE PEOPLE HAVE SPOKEN

FOR LARGE FOOD COMPANIES, “THE CUSTOMER IS ALWAYS RIGHT”—WHETHER THE AG INDUSTRY LIKES IT OR NOT

BY KELSEY JOHNSON

These days, a trip to the grocery store can be an overwhelming experience.

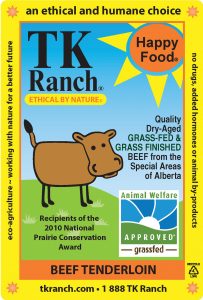

Gluten-free, GMO-free, MSG-free, free-run, cage-free, hormone-free, organic, all-natural, pesticide-free—the list goes on and on. Row upon row of descriptors and labels plastered on food packaging, all aimed at better informing the consumer.

As a consumer, the amount of choice and selection can be baffling. As a producer, determining what is and isn’t simply a short-lived trend can be nearly impossible, making it increasingly difficult to succeed in an increasingly globalized marketplace. This begs an important question: Has Canada’s agriculture industry been too slow to react to the growing demands of the consumer? Or is the situation more complex?

Back in the day, conversations about “social licence” (the industry term used for the right to farm, grow food, raise livestock and more with public backing) weren’t of significant concern to Canadian farmers. Farmers and consumers were worried about food safety and nutrition, cost and access, but, for the most part, conversations centred on farmers being stewards of the land, with their practices backed by science. While food remained an integral part of community life, the industry’s practices were generally unquestioned by the broader public.

“I personally think that it wasn’t really an issue,” said Sylvain Charlebois, dean of the Dalhousie University faculty of agriculture, when asked why the agriculture industry has been slow to respond to consumers’ growing demands. “Most people felt current practices were acceptable to the broader public.”

According to Charlebois, the industry has benefited from new trends, but now it is being asked to become more accountable. Not only that, it’s being asked to provide evidence that its practices are acceptable to the broader public.

“It’s not something the industry was ready for or accustomed to,” he said, adding the sector may have “underestimated how impactful these new trends would become.”

Today’s food marketplace is a competitive, consumer-driven, international supply chain—one where big industry players are choosing to make business decisions aimed at satisfying consumers’ ever-shifting demands and desires.

“Consumers are the new CEO of the food supply chain. You sort of have to listen to them,” said Charlebois, who formerly taught at the University of Guelph and has written extensively about the modern relationship between the consumer and the agriculture industry. “On the other hand, you have to recognize that [consumers] are making decisions based on imperfect information. So, there is some confusion out there.”

Given the interconnectedness of the food supply chain, those business decisions can have a profound effect on primary producers, who may need to make significant investments and adjustments on their farms—investments some feel are unnecessary or even risk setting back their industry.

Consider Canada’s decision in 2014 to move away from the use of gestation crates in sow barns. Animal activists and some consumers, including Canadian actor Ryan Gosling, argued the crates were “inhumane” and “archaic.” Meanwhile, hog farmers insisted the crates were integral to animal welfare, arguing the systems protected piglets from being crushed by their mothers.

McDonald’s, Tim Hortons, Burger King and Wendy’s have all committed to sourcing their meat from humanely housed animals, while Costco Canada, Loblaws and Walmart Canada pledged to move away from gestation crates by 2022.

SEPARATION ANXIETY

The widening gap between the consumer and the farm has challenged the agriculture sector for years. This disparity has been buoyed by the steady migration of people from rural to urban areas.

Fewer Canadians are farming, while the country’s farmers are getting older. In 1991, Statistics Canada data showed Canada was home to 265,495 farm operators under the age of 55. By 2011, that figure had dropped by almost half to 152,015.

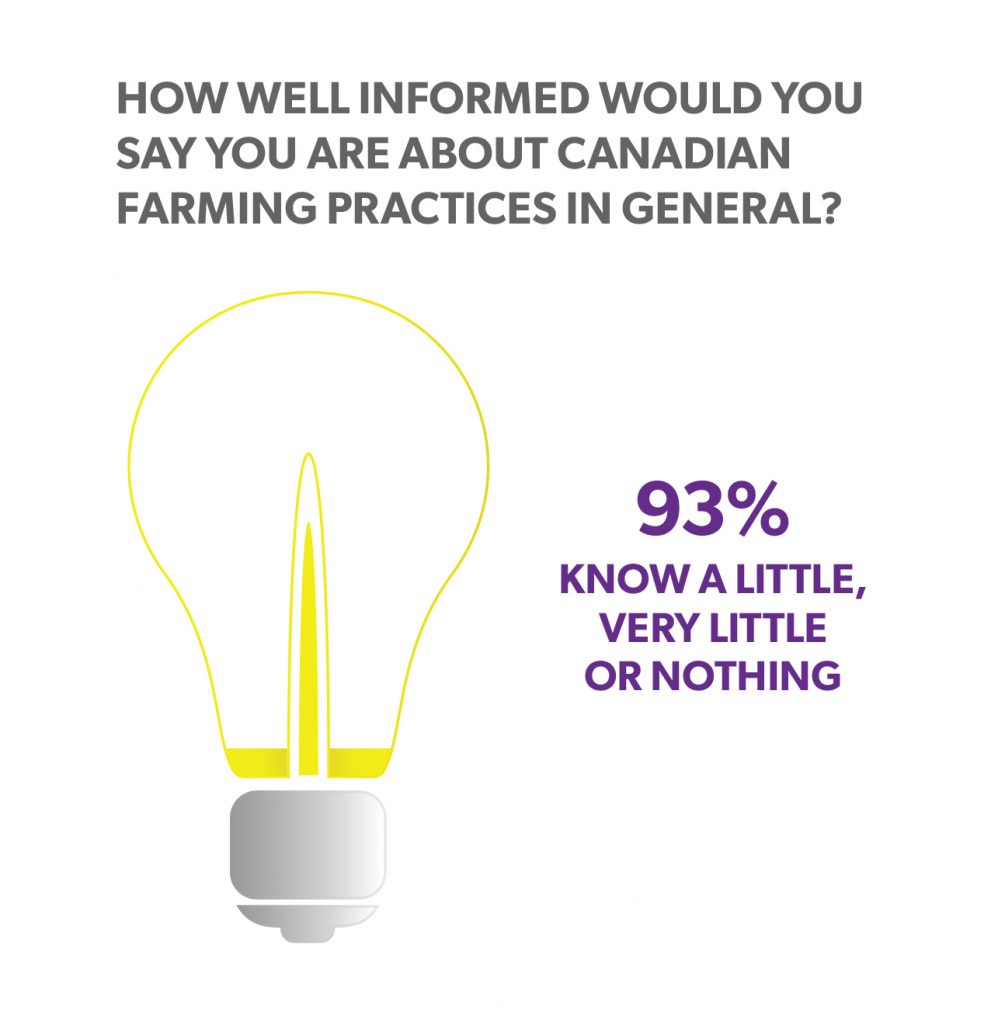

In an effort to find out just how much Canadians know about Canada’s multibillion-dollar agriculture industry, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada conducted 18 focus groups in 2014 with rural and urban residents in eight different municipalities. Each meeting lasted just over two hours, with the focus groups made up of eight to 11 participants over 18 years of age.

“Findings from this series of focus groups clearly indicate a relatively low level of awareness, particularly among urban dwellers, of the current state of the [agriculture] sector and its contributions to provincial, regional and the national economy,” the report noted.

Few among those surveyed were aware of the sector’s economic clout—it contributes some $100 billion to the national economy each year. Others expressed surprise at the fact that the industry is responsible for one in eight jobs in Canada. Only a handful of the survey’s participants had visited a working farm.

At least one person tied their knowledge gap to a lack of advocacy and education about the industry from Canadian farmers. “I feel like agriculture is silent in Canada,” the participant noted.

It’s an observation that hasn’t escaped some within Canada’s agriculture industry. Canadian Federation of Agriculture president Ron Bonnett has long insisted the sector needs to do a better job of telling its story. “We are too modest,” Bonnett told delegates at the Federation’s annual meeting in Ottawa in February.

Consumers and politicians alike, he insisted, need to be told about the sector’s economic importance, while the industry needs to start highlighting its achievements in areas like innovation and environmental stewardship.

Andrew Campbell is one Canadian farmer who has made an effort to bridge the gap between consumers and the agriculture industry. Campbell is an Ontario dairy producer and former agriculture journalist who has taken it upon himself to open his barn doors to curious consumers. In 2015, as part of his New Year’s resolution, Campbell pledged to take a picture on his farm every day for a year, posting the photos to Twitter under the hashtag #Farm365. The project eventually went viral and gained national media attention. Campbell said his followers doubled in 24 hours. Eventually, more and more farmers followed his lead, posting photos, despite threats to their operations from some animal rights activists.

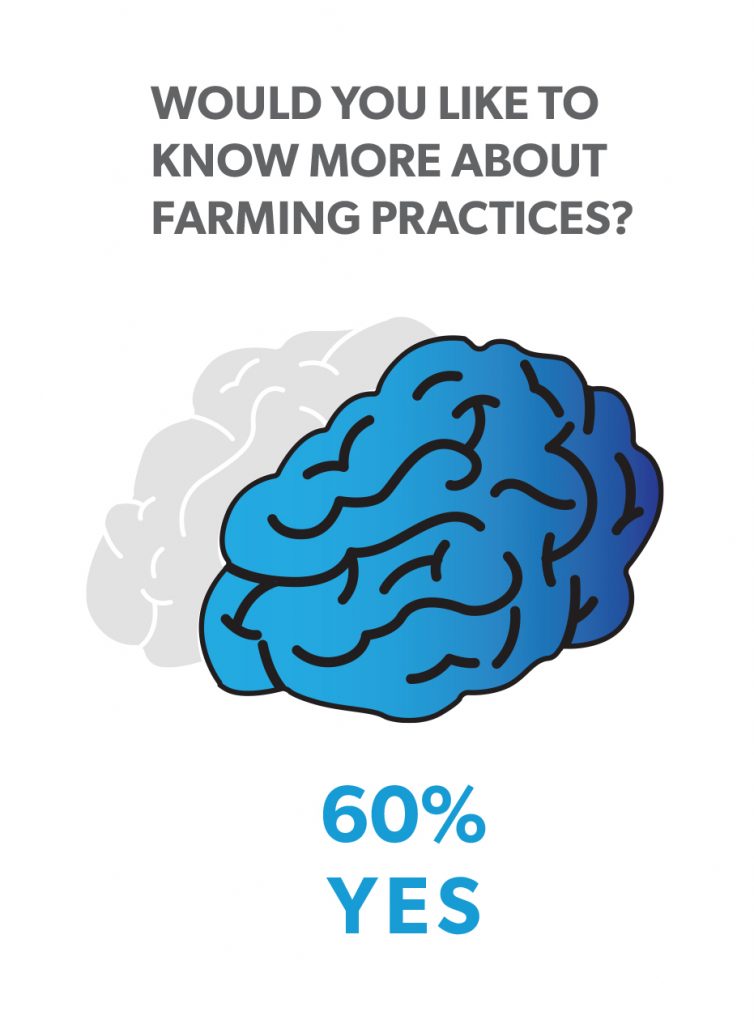

“Consumers, as I’d hoped and as I’d wanted them to be, are generally interested in what is happening on farms today,” Campbell said of the project during a recent webinar aimed at encouraging farmers to talk to consumers about agriculture and their food.

“We do have a really positive story,” he said. “We as an industry have to be present in the online conversation because when people are looking for the information, they’re going to go online, they’re going to use Google, they’re going to use social media. If we’re not there, in that space, presenting our side of the story, then to the consumer our side of the story doesn’t even exist. And we really cannot afford to let that continue to happen.”

Despite the increase in consumer outreach initiatives throughout the agriculture industry, farmers shouldn’t be patting themselves on the back just yet. Charlebois isn’t convinced education and advocacy campaigns will make a dent in consumers’ agriculture knowledge deficit. “You can’t really institutionalize the education of consumers,” he said. “You’re at the mercy of trends.”

BRAIN DRAIN

As the divide between consumers and producers continues to widen, research shows people are looking for direct information. Thankfully, the agriculture industry has one thing going for it in this regard—people trust farmers.

A 2016 online survey of 2,510 Canadians by the Canadian Centre for Food Integrity (CCFI) found Canadians’ impressions of farmers have warmed, with 69 per cent of those surveyed saying they trusted farmers for information about their food—the highest level seen in 10 years.

Doctors, nurses and medical professionals came in second, at 65 per cent.

Yet, the report warns that agriculture’s old strategy of relying on science to deal with misinformation and questions about growing practices, animal welfare and other concerns simply doesn’t cut it anymore.

“Historically, when under pressure to change, the industry has responded by attacking the attackers and using science alone to justify current practices,” the report reads. “Too frequently, the industry confuses scientific verification with ethical justification. Not only are these approaches ineffective in building stakeholder trust and support, they increase suspicion and skepticism that the food industry is worthy of public trust.”

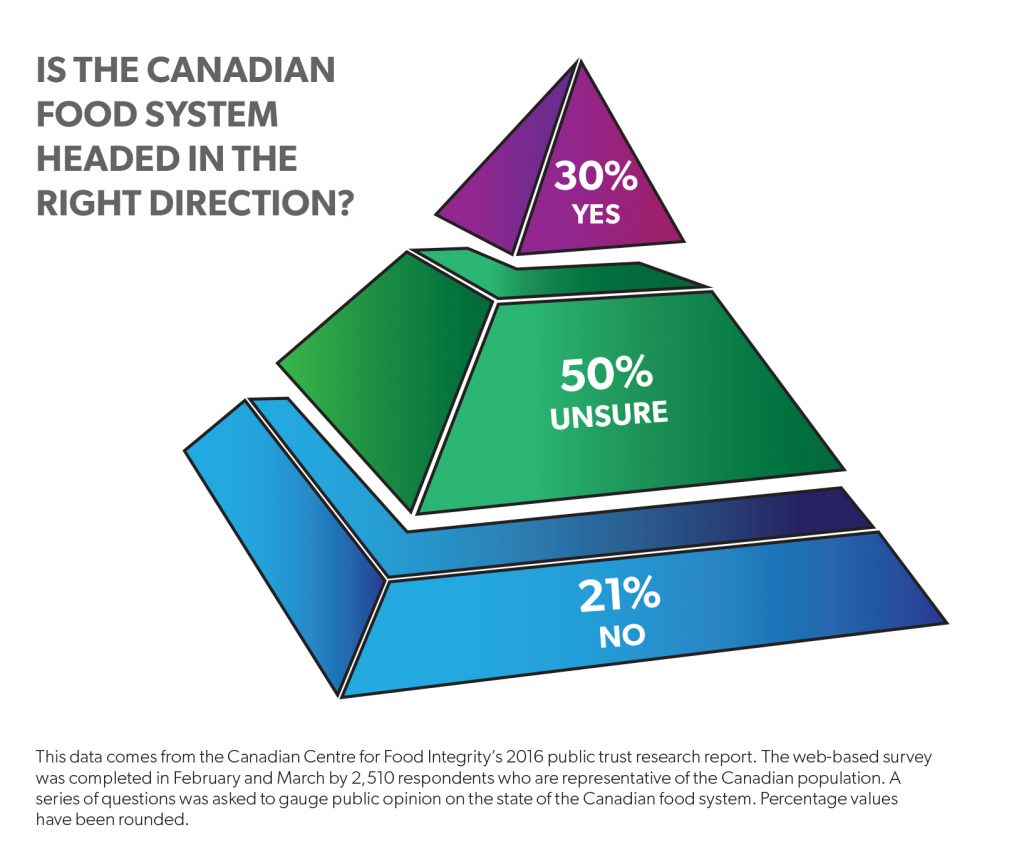

Half of those surveyed said they were uncertain about the direction in which Canada’s food system was headed, the CCFI found, compared to one-third of Americans.

Meanwhile, many of those surveyed highlighted increased concerns about the rising cost of food, the humane treatment of animals, food safety and ensuring Canadian food security.

BURGERS AND BUCKS

If consumers lack an understanding of general farming practices, why are companies conceding to their demands around how food is produced? According to Charlebois, the answer is simple: they’re business decisions, designed to carve out an edge.

“At the end of the day, it boils down to price … It’s a very competitive marketplace,” he said. Decisions are made even if those business moves risk angering farmers and ranchers in the process.

“When you’re dealing with food, societal trends, any rules based on science go out the window. It’s based on emotion, it’s about experience,” he said. “I think that what needs to happen is that companies need to address and manage perceptions, more so than factual evidence.”

Consider A&W’s ongoing “Guarantee” campaign. When the restaurant chain announced it’s new Better Beef Campaign (since renamed the Beef Guarantee because consumers weren’t connecting with the “better” part) in 2013, Canadian ranchers were livid.

The move meant A&W would no longer serve beef in its restaurants produced with hormones or steroids. In order to do so, the company needed to source meat from outside of Canada, with most of it coming from the United States, Australia and New Zealand.

Many ranchers took to Twitter to voice their displeasure, threatening to boycott the restaurant chain, but A&W refused to back down. More than two years later, the company insists the move was well received overall and has since extended its guarantee to include eggs, poultry and bacon.

“We’re selling more beef. We’re having more people tell us they’ve come back to eating burgers again,” Trish Sahlstrom, A&W vice-president of purchasing and distribution, told attendees at the Canadian Farm Writers’ Federation’s annual conference in September 2015. Same-store sales, she added, had increased by approximately seven per cent.

Sahlstrom insisted the restaurant’s decision was solely driven by consumer demands. “We see it as a responsibility for us to do what the consumer wants—not try to get the consumer to do what we want, as frustrating and as difficult as that can be.”

Consumers, she said, had felt the burger chain was out of touch—a perception that was hurting the company’s bottom line. “Consumers were saying, ‘Where’s the evidence? I no longer trust just that it tastes good. I want to know where it came from,’” she said.

While A&W survived the industry backlash and stuck with its beef guarantee, other restaurant chains and distributers haven’t been able to weather similar storms.

In April, Vancouver-based restaurant chain Earls announced it would stop sourcing Canadian beef for its menu because the company, which uses more than 900,000 kilograms of beef annually, couldn’t find a capable Canadian supplier that met the chain’s newly introduced Certified Humane welfare standards.

The Certified Humane program sources beef that is free of antibiotics and steroids. The meat must also be slaughtered according to criteria outlined by animal welfare advocate Temple Grandin.

The company’s decision was immediately met with a fierce backlash. Furious ranchers argued the move was nothing more than a marketing ploy that tainted the reputation of the rest of the beef industry in the process. Within 24 hours of the announcement, the hashtag #BoycottEarls was trending on Twitter, with several politicians, including Alberta Agriculture and Forestry Minister Oneil Carlier, Saskatchewan Agriculture Minister Lyle Stewart and former federal agriculture minister Gerry Ritz taking to social media to voice their support for Canada’s beef industry.

After a week of trying to extinguish the flames on social media, Earls backed down. In a video released by the company, Earls president Mo Jessa admitted the company had “made a mistake.” Earls, he said, would now work with several Canadian suppliers to satisfy its beef needs.

“We want to make this right. We want Canadian beef back on our menus so we are going to work with local ranchers to build our supply of Alberta beef that meets our criteria,” Jessa said in a statement.

Charlebois said he doesn’t fully understand why the company apologized. “I’m still not sure why they did that,” he said. “They made a business decision.

“It’s hard to blame a company in doing so. They were just trying to respond to what the market was looking for. Earls was looking for evidence it was able to convey on a menu and that was something that Canadian ranchers couldn’t do.”

Still, Charlebois said the fallout perfectly encompasses how fluid the food market has become. “The Canadian consumer is different today for all sorts of reasons—globalization, health trends, ethnicity, demographics,” he said. “And, it’s going to be even more different in 10 to 15 years’ time.”

Comments